A Body Knots: Laurie Kang at Gallery TPW

28 November 2018By Jenine Marsh

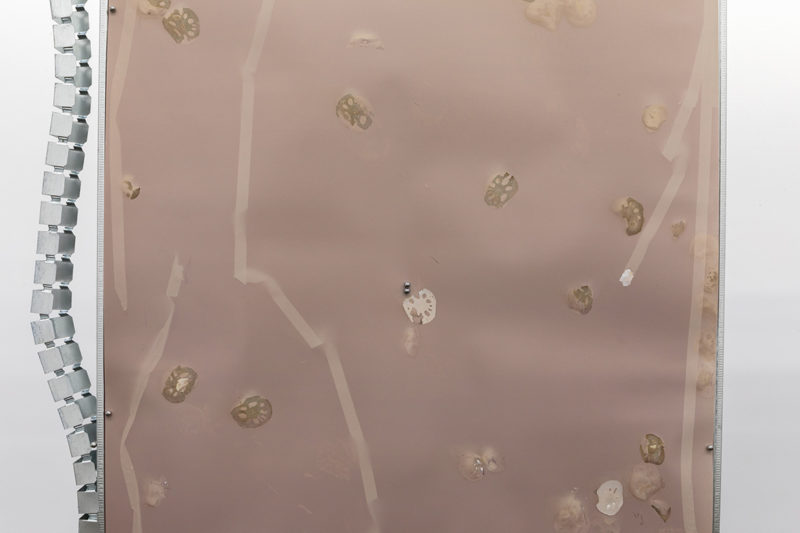

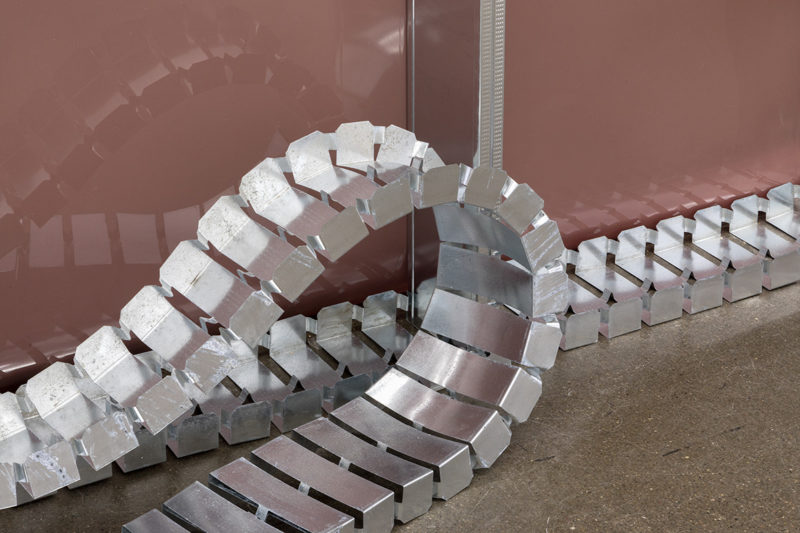

I view Laurie Kang’s A Body Knots on my phone, as images. I’m on another continent, missing the show. But feeling that I know her and her practice pretty intimately makes up for some, though not all, of the texture and spacing that the real thing provides. At Gallery TPW in Toronto, a steel skeleton wall of studs and flexible tracking marks a new—albeit permeable—barrier through the two adjacent gallery spaces. In the second and larger gallery, four analog photograms of un-fixed, thickly applied darkroom chemicals on overlarge paper hang loose and heavy from the studs. Although forever halted in the jpgs, these photograms’ chemicals will continue to develop and change, reacting slowly, subtly, to the light in whichever space they occupy. Tiny silver spherical magnets hold the prints in place.

Having been exposed to natural light in Laurie’s studio, a light sensitive film is on one side, a uniform velvety taupey-puce that would suit a powder room. The other side of the wall, delineated by these draping sheets, photo paper is marked and printed with indefinite images of muddy prints, fleshy smears and makeshift grids. The photograms’ almost-pretty colour range of puce-taupe to paper-white to grey-pink to brown-maroon is reminiscent of dried and dusty roses, of unsold day-old steaks, or of a lingering intertwined fragrance of perfume and cigarettes. And, like a fragrance, these works shift between a barely-there whiff; a paper thin sparseness—and a nearly overwhelming excess of sensation.

Cast out on long threads into the wifi, these paper walls are transformed into a transmittable skin of pixels on a backlit screen. Kang’s is an image-based practice in which bodies and materials are not subject but embodiment (that is, not solidly nouny, but fluidly verby). And now that the show is down, and this body of work has been translated into digital files, the conversion feels something like the scale shift from body to genes, from skin to code, with no possible return to the tangibly physical. The transformation from image-based practice into a more “pure” jpg image is permanent. But is this conversion lossless? We are so used to seeing exhibitions flattened onto digital screens; if there is a loss of material or ontological significance, it is a banal one, as documentation often seems to take precedent over the actual exhibition, and the flattening clarity of online viewing becomes a strategy for easy visual consumption. But, seen from another perspective, is this translation from matter (in the gallery) to image (on my phone) of A Body Knots one that might possibly be in productive collaboration with its flat, reflexive, un-fixed verbing? A complicating complimentarity? (1)

In a floating display window on my shitty phone, the gallery is pressed into a patchwork of rhombuses, multiplied into many angles of itself, and projected into the screen dimension. Her photos are sculptures—or, actually, mirrors, and looking into them, the body dysmorphia is profound. What I see reflected back at me is a flesh of holes, shifting unfixed in shallow form. Even an adult human who should be done growing—who should be grown-up into something calcified—will change again as calcium dissolves, shrinking, and as the skin’s surface is worked in like leather, a million folds that eventually accumulate into something like liquid. These images are likewise in a state of continual chemical development, as they are visibly changed by whatever environment they are in. Studio and gallery light bleed into each other. Though they might not be visible to the naked eye, even the briefest shadows and reflections leave their mark. Every possible space is a darkroom. The darkroom is eviscerated.

The steel studs that hold up the photograms make a mirror wall that we are already behind, whichever side we stand on. Look into a wall of mirrors, and each one says something different. Temporal and temperamental, the wall shimmers like quicksilver, like chiffon in a fan’s heavy breath under studio lamps, like an expression not hidden quick enough. The screen on my phone is a little cracked, and these mirrors are too—mirrors already so dramatic, so theatrical, never really believable—like actors, like reflections. I can’t go to plays; the disbelief exhausts. In the theatre I sit on the other side of the mirror, where I upstage and critique performance with my own realer presentation.

But I’ve been watching a lot of RuPaul’s Drag Race. It’s all critical faces talking through the mirror at each other, reflecting back different varieties of realness. A bucket or bowl of something viscerally gelatinous was left behind the mirror wall, silicone and pigment and what might be a soaked sock—could this be me? Where do I stand in the image-making process? In the awkward embodiment standing before the mirror? In the image spreading and developing across it? Or in the lumpy, unspeakable thing caught in a stainless steel bowl behind, backstage, almost literally gagging on realness?

The taupey hues and razzle dazzle sparkle of silvery metal are only superficially feminine. Calling this work feminine means you haven’t got a clue. Here we are, caught between audience and actor, viewer and object, stuck willingly in the unknowable murk of the intermediary, inter-netting. (Every time I talk about the internet I feel like I age about five years—there is no Net as thing, no Net as out-side space anymore. Like the map drawn as detailed as the world it describes, that has stretched just as wide as the world, the Net stretched until we fit perfectly inside.)

Kang’s images bend the mirror, to show the image to itself. Her work experiences the drama of self-awareness, discovering its own body in a remarkably un-anthropomorphic process. That brief moment when I first glance at myself in a mirror that I thought was a doorway or window, and my expression shows back an accidental look that is quickly wiped away—just a twitch, a tick, nothing at all—this look that shimmers momentarily is the look that sees the un-anthro and the un-morphed. It sees itself before it remembers to be human, it sees the strangeness of not only one’s reflection, but of one’s self and one’s body, as not the safely relatable self presented.

Making from both a racialized and gendered position, as well as from a place of twinship, there’s a fluidity and ambiguity of identity that Kang’s work continually probes. As a cis-gendered Korean-Canadian woman, she may embody, bend and break many projected/reflected roles, every day. And as an identical twin, Laurie has always had a full-length mirror by her side, maybe even dressed the same, paralleled since birth. Her twin now lives on the other side of the continent, but even that three-hour time difference might not erase the feeling of being in two places at once that I imagine twins might occasionally, accidentally feel. Always compared and yet always combined, always exaggeratedly singular and plural, a twin must always know—and see—that there is more than one way to be in the world.

Looking past my own reflection cast on my cracked phone screen, and into these ever-flowing, ever-fluid mirror walls, what is human turns out to be just bad acting. And just like a bad actor’s fleshiness shows between cracks in their assumed, glasslike character, something shows in the fractured mirroring-image. The anthropomorphic theatricality of sculpture is here transmorphed into a glaringly supernatural, tangible realness. As the body reflects back on itself, a strange extra option is presented, a neither between images, an ether, in which there is space to be something other than what is called “human”.

1. Complimentarity is a term used in Karen Barad’s book “Meeting the Universe Halfway” 2007, Duke University Press, p. 19.

A Body Knots ran from May 5 to June 9, 2018 at Gallery TPW in Toronto.

Feature Image: Installation view of A Body Knots, 2018 by Laurie Kang. All photos by Jimmy Limit, courtesy of Gallery TPW.