Attunement’s Discourse in Crisis & Connection

21 February 2025By Mic Jones

An experiment in reading experimental choreography & theory on crisis through an experimental book on love.

Prologue

For their winter 2024 program, The Blackwood Gallery and Toronto Dance Theatre curated a paired program of choreographic works—Weathering by Faye Discoll and Fran Chudnoff’s FACE RIDER—alongside a suite of transdisciplinary panels, The Attunement Sessions. From Discoll’s choreography distorting the scale and rate of climate collapse to Jack Halberstam’s talk on Unworlding as a creative and social practice of generative refusal, this trans-disciplinary program unfolds in the ruins of certainty and individualism, our precarious present tense. These intellectual experiments and experimental performances call for a heightened awareness of our interdependencies and impact(s)—relationally, historically, culturally, environmentally. A heightened awareness starting with an attuned sensory system. Western capitalism works hard to dull our senses because vulnerable points—be it nerve endings or marginal identities—are also powerful places. Love evokes all our senses and changes us radically.

Gay and a devout mommy’s boy, French cultural theorist Roland Barthes thought deeply about love as the shared precarity of humans, a preoccupation culminating in his 1978 genre-defiant book, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments. It’s a kind of index of archetypes we enact or inhabit when in love, each somehow both nuanced and familiar. As many of us have been in love before and felt our senses anew because of it, these states of being Barthes outlines could be the ideal framework from which to answer The Blackwood and TDT’s call: can we wake our sensory edges to what’s too big to see—the way we shape each other, the way we’ve shaped natural cycles of the climate into a collapsing one, the way in which that climate in collapse is now shaping our bodies—so can we can feel the impact? I’ve chosen five of Barthes’ archetypes—Contact, Reverberation, Catastrophe, Waiting, and Alternation—as points of view to help pressurize such a sensibility.

Contact

Interior discourse provoked by a furtive contact with the body (and more precisely the skin) on the desired being.1

The horizon is a bodily one. Choreographer Faye Discoll’s Weathering is a torrent of touch, a thesis on entanglement. Ten dancers shift, initially imperceptibly, within an interconnected tableau vivant on a raft-like surface that turns in circles, and over time, speeds in relation to the bodies’ quickening movement. Reach and orientation are two factors that inform who one touches and is touched by on this stage, the same way it does beyond it. As the raft in Weathering spins faster, the meaning of contact becomes synonymous with dependency: bodies become handles, touch is not furtive anymore. To reach for another newly in view, one dancer releases their clasp on one hand, who then tumbles off the platform. This precarity of holding on is unevenly distributed amongst the performers. The white bodies and masculine bodies hold comfortable positions, squats and lunges, for much longer than the micro population on stage. And once they do tumble, it is with ease that they reach for support. In this way, Weathering mirrors our social reality of how belonging modifies, amplifies, and minimizes one’s reach into the world.

All the while, each rotation of the platform reveals a new context of togetherness. New points of contact continuously taking shape and continuously dissolving. As you watch these entanglements reorganize on the turning platform, a sense of time that disrupts objective measurement grows. Time not as the accumulation of years, but as the accumulation of touching and being touched, of relationships building and crumbling—the urges and hopes and fears that our entanglements mark us with, reshaping how we see ourselves and each other and how we move through the world. In Weathering‘s companion reader, the line: “we are touched into existence.” Across from me in the audience, I see a hand placed on the knee next to them, a freckled arm extends along the back of their neighbour’s chair in the row below—gestures Barthes describes as “a kind of festival not of the senses but of meaning.”2 In a deep lunge, head hovering above another dancer’s chest sprawled flat upon the raft’s surface, drops of drool pour from one body and pool onto another, seeping into their pores. Barthes calls the mark that relationships form “a radical chasm (at the ‘roots’ of being), which cannot be closed, and out of which the subject drains, constituting himself as a subject in this very draining.”3 What happens when we consider the body as a compost of everything it has touched: a hand held under the dinner table, the way they squeezed your hand, the last time you held their hand, this magazine in your hands right now. Consider how composts tend to leak—which in this case means the leaking of our crushing, cruising, falling in love, breaking up, moving on, negotiating multiple and ongoing relationships like these dancers on the raft do and must. Relational becoming is then more of a decomposition: past, present, future all mixing up. This kind of undoing we could think of as a degenerative aesthetic.

Reverberation

I am wedged between two tenses, that of the reference and that of the allocation: have gone (which lament), you are here (since I am addressing you). Whereupon I know what the present, that difficult tense, is: a pure portion of anxiety.4

As the hour run-time of Weathering slides, we witness a historical process of contact depositing in each performer an infinity of traces without leaving an inventory. A dancer’s long black hair slowly sways as they struggle to manoeuvre out of another’s hold—and once they do, scans for that former harsh-grip with a gaze diverted from the body that tenderly holds them in the present moment. “In an undertone, the imperfect tense murmurs behind this present,”5 Barthes writes of such reverberations. Another pair of dancers move through a whole album of intimacy—standing, sitting, laying down—until the only point of contact that remains is their feet, ankles locked together. While the rest of their bodies steady against other bodies, this pair negotiates new touch so as to not let go of each other. It’s clear this abiding hold makes new touch more difficult, compromises comfort. It’s clear neither can see the other any more and still the touch persists. It’s only after their mutual foothold breaks and they reverberate the same hold with different partners that the couple make eye contact again. Then wedges into now colliding with what’s next and each body becomes not-quite-one, touch is rendered here as the opposite of singular.

A dancer with visible top surgery scars is raised above the melange by the melange and tears up pages of paper—leaving torn sentences, fragments of text that now populate the theatre floor. Barthes says “what echoes in me is what I learn with my body.”6 Was it myself I saw reverberated in this scene? Why it continues to reverberate as I call again this month to check my place on the surgery waitlist amidst a stack of medical files bearing my old name, paper I hope to someday shred exactly like that dancer did.

Another reverberation: a gleam in one particular audience member’s eye that I know nothing of, other than its gleam. A gleam I thought about during the exercises Weathering’s Intimacy Coordinator, Yehuda Duenyas, led for Attunement Session 2 just a few hours before showtime in the same theatre room.7 We each held the gaze of a stranger for three minutes that felt more like thirty. In a whispered tone, Duenyas prompted us to imagine the other held as a baby, their first crush, embraced in a kiss, and in heartbreak. Eye contact was the only kind of touch we shared, and we touched that way again in the lobby theatre after Weathering finished. We smiled, no words exchanged, blushing in our shared knowledge of nothing but each other’s irises and the intimacy we imagined each other experiencing, brief and gone.

On my streetcar ride home, I thought of other blue eyes I have known, and tried to recall the eye colour of people I’ve slept with. Mostly I could not. So, instead, I noted the hues of all the eyes I could see on the TTC.

Catastrophe

A situation without remainder, without return.8

Throughout Weathering, Choreographer Faye Driscoll scatters all kinds of litter across the stage. Clothing, vapes, cell phones, plastic water bottles, sparkles, scraps of paper flood the scene at a steeply increasing rate. All this casual human litter eventually seeps beyond the stage, into the audience. Reality even amplifies the scene, yesterday’s litter under your seat. Mathematicians define catastrophe as the disturbance of one system by another.9 Driscoll distils a precise image of our climate’s catastrophe, in duration and proximity, as human animals who have disturbed Earth’s ecosystem and are now being pushed off because of it. Her pacing of the choreography from polarities of micro to macro movements counters the way Western capitalism makes the climate crisis—a situation indeed without remainder or return, Barthes’ definition of catastrophe—feel distant and abstract, reversible. In Weathering, we see it all unfold in the length of a Netflix special and, as bodies and litter catapult into the audience, the implications of our interconnected reality is made unignorable.

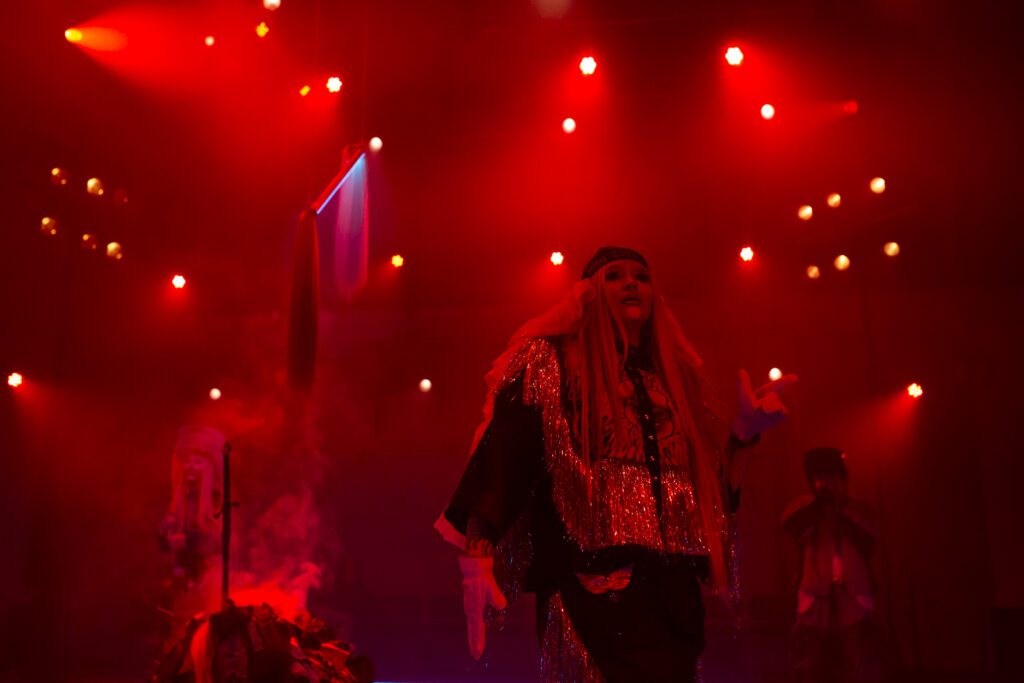

Choreographer Fran Chudnoff’s FACE RIDER dives into Driscoll’s wide shot of Earth’s climate crisis, smacks into a few Wi-Fi towers and satellites on the way down, before belly-flopping into a swamp. The sea is by now gone. The earth, a mess—and a mess that is beyond “fixing.” The question is no longer about improvement but rather how to deal with it. The performers of FACE RIDER deal by being together in it, slipping around in the bog, effacing gender, recycling the glitter of the early two-thousands’ with campy internet aesthetics, animated like a polaroid of our present.

The aesthetic of FACE RIDER is an aesthetic of mutation, like capitalism. Bedazzled denim, neon wigs, and massive metallic bows are all reassembled in some way, the human form muddled: cowboy boots with a sneaker shoe, True Religion jeans back-pockets belted around the knees, a trucker hat with multiple brims. My notes were mainly this, a record of the costumes. It was half-way through the performance before I noticed the components of a human-size-pile centre stage: discards of costumes with a sword plunged inside, visually reverberating the infamous Excalibur stuck in stone. But here, a mass of slightly smoking human waste replaces the natural minerals as the sword’s resting place. Red, purple, blue, hazy, of course, neon lit—my eyes full of sensory pollution.

In both ensemble pieces, there is no soloist. And this is key to the shared thesis of TDT and Blackwood’s collaborative program. The dancers must connect with one another to sustain the performance. In Weathering, this connection is literal contact points, whereas Face Rider’s performers do so in a more narrative way; a break-up unfolds on stage, with mics in the dancers’ hands, and as they talk through attachment styles, the now ex-couple finds a way to still be friends as roommates, for the sake of paying rent. The progression of each dancer’s journey bends into a question of how to work together in chaos beyond any individuals’ control.

Images: From FACERIDER, 2024 by Fran Churnoff. Photo by Marlowe Porter courtesy of Blackwood Gallery.

Waiting

I have no sense of proportions.10

“What are we supposed to watch?” the small child beside me asks their mother ten minutes into Weathering while the raft turned ever so slightly and we wondered if the dancers were in fact moving at all, uncomfortably aware of our own stillness because the whole theatre was almost only stillness. So it felt sudden when, in less than an hour, the raft spins so fast that dancers are unable to hold on, spill off stage, catapult through the audience and around the theatre. But it was not sudden, it was gradual. The raft’s spinning pulls apart the tableaux’s form the same way Earth, collapsing under the weight of our waste, is trying to push human presence from its surface. Driscoll’s pacing emphasizes the way waiting stretches the present (Barthes: “that difficult tense”11) to make now seem like forever, giving the false sense that more time is endlessly approaching. Prolific queer theorist12 Jack Halberstam’s talk on their concept of Unworlding, presented at Attunement Session 3,13 fleshes out the same ideas in theory as Weathering and FACE RIDER do in performance.

It’s difficult to speak with confidence and integrity about world building anymore when the environment is in a state of no-return, Halberstam argues, and I agree. The theorist turns to a diverse selection of creative work that refuses the easy solution of continued capitalist progression for the more difficult prospect of unmaking. Halberstam cites examples such as Beverly Buchanan’s Urban Ruin sculptures of the late 1970s, how she used New York City’s rubble to speak of and through buried existences; the performance experiment, Becoming an Image, in which artist, Cassils, continuously slams their body into a slab of clay, their trans body being moulded by and moulding the clay in the process, a mutual undoing of maker and material; Octavia Butler’s 1979 novel Kindred and the protagonist’s bodily mutilation from time travelling, how Butler uses genre elements of science fiction to convey the irreconcilable, ongoing, symbolic loss that continues from slavery and and the institutions (real estate, prison, police) designed as its lineage. Halberstam unites these creative works by tracing how each disrupts colonial teleological narratives of improvement and incites questioning of the imperial concept of “world building” that has delivered to us this shaky present of late capitalism and climate crisis.

It is this kind of questioning that precedes ways of doing, thinking, and being that slow down to acknowledge the ruin and work with the rubble. Like Driscoll’s choreography, Halberstam’s theory of Unworlding does not offer a blueprint for action, but rather a conceptual toolbox toward awareness. This awareness is a tool to refuse the way the world currently operates. This awareness disrupts the message that “it can wait.” In action, Unworlding could look like protesting the absence of affordable housing, an issue relevant in every city across “Canada” today. From such actions, Halberstam moves us to question what it would be like to live in a city without land ownership. When used in local and specific situations like this, Halberstam’s work and writing indirectly incite us toward collective action of undoing systems never designed for collective well-being.

Halberstam’s thinking reaches beyond the humanities toward the defiance of low physics. The second law of thermodynamics is that the universe is unwinding and the only certainty is uncertainty.14 Similarly, the more Weathering’s platform spins, the less we know about the bodies on it, the speed of movement blurring our sight. There is no complete theory of mathematics, only indeterministic gestures. Pretending to address his beloved, Barthes asks:“What would happen if I decided to define you as a force and not as a person? And if I were to situate myself as another force confronting yours?”15 Driscoll and Halberstam would reply, of course we are forces, not just crashing into one another, instead we are colliding with the trees and seas and dirt, all of it, bugs and volcanic eruptings—your question is too small, we can’t keep waiting on such delusions of self importance to inch toward revelation of our entropic reality.

As I witness Weathering’s performers’ micro gestures grow into macro grasps of desperation, the feeling of complicity builds. The horror of all this is that it has happened already, and now, as a species, we’re on our way out.

Alteration

The subject suddenly sees the [beloved’s] good Image alter and capsize.16

Alteration is the dissonance that smears across the faces performing in Weathering, as mutual embraces tumble into asymmetrical groping. Alteration is the dissonance that bursts on stage as a couple in FACE RIDER embark on their situationship “define-whatweare” talk, progressively shedding layers of wigs and belts and assumptions of exclusivity that, only a minute earlier, held together a care-free, post-monogamy, futuristic cowboyish aesthetic. “The horror of spoiling is even stronger than the anxiety of losing,”17 Barthes warns of the Lover’s tendency to turn away when sensing something does not add up. “Shapes of life change as we look at them, change us for looking,”18 writes Anne Carson, reflecting on hints she missed that signalled her first husband’s true nature; a man who cheated on her, and worse: stole and plagiarized her notebooks. Convenience fissures, wholeness fragments. Or as Barthes writes, “the fairy tales, no longer flowers, but toads.”19 Notice how Carson’s repeated word choice locates our senses as a transformative force, both internally and outwardly. The Lover’s panic in reckoning with the network of implications that misapprehension provokes is an Unworlding moment: “I hear a counter-rhythm […] the noise of a rip in the smooth envelope of the Image.”20 The portal to Unworlding at a larger social scale is sensing that such altered appearances surround us, and they are the foundations of every state and institution that serves it.

Halberstam’s “un” is an agile and capacious “for,” transforming the negative to genius radical inclusions like any underground. To make a politic that is also a poetics out of a prefix—unworlding, unwinding, uncertain, unmaking, undoing—is a special kind of brilliance.

Our Epilogue

Blackwood Gallery and Toronto Dance Theatre’s paired program offered glimpses of other ways of thinking, being, and doing, which give attention to impact at the bodily, social, ecological scale. Weathering’s dancers fall off the raft until they give up getting back on it—undressed, they find seats in the audience, and with us watch in silence as the raft, covered in all kinds of waste, floats around empty on the stage for the show’s final two minutes. At the start and end of FACE RIDER, a dancer rides a bicycle in circles around the steaming trash pile, millennial-pop playing, and everyone watches uncertain whether the show is over, in the same way they thought they were late walking into this scene already happening when the theatre doors opened. After their talk, Halberstam refused to sign my notebook and said “you don’t need that but come find me in New York City, we’re not yet done talking.”

None of these performances or talks ended. They fell apart. Into a torrential silence. The same way Barthes describes the process of love leaving. I still can hear them quietly booming now, out of frame, because we are the frame.

- Roland Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse: Fragments (New York: Hill & Wang, 2001), 30.

- Ibid., 67.

- Ibid., 190.

- Ibid., 15.

- Ibid., 216.

- Ibid., 200.

- “Attunement Session 2: Erotic Edges, Queer Intimacy, Wet Dreams.” Artist Talk with Yehuda Duenyas, John Paul Ricco, and Erin Robinsong, presented by Blackwood Gallery & TDT, Daniels Spectrum, January 21, 2024.

- Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse, 49.

- “Catastrophe Theory,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, April 2, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/science/catastrophe-theory-mathematics.

- Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse, 37.

- Ibid., 15.

- You can buy an editioned silicone mould of Jack Halberstam’s actual fist from Art Metropole in Toronto. See here: https://artmetropole.com/shop/8576.

- “Attunement Session 3: Data Bodies, (De)Generative Aesthetics, Unworlding.” Artist Talk with Fran Chudnoff and Jack Halberstam, presented by Blackwood Gallery & TDT, Winchester Street Theatre, February 10, 2024.

- “Second Law of Thermodynamics,” Encyclopaedia Britannica, April 2, 2024, https://www.britannica.com/science/second-law-of-thermodynamics.

- Barthes, A Lover’s Discourse, 135.

- Ibid., 25.

- Ibid., 28.

- Anne Carson, Plainwater (New York: Random House, 1995), 190.

- Ibid., 28.

- Ibid., 25.

The Attunement Sessions ran from January 20–March 16, 2024 between Daniels Spectrum & Winchester Street Theatre in Toronto, ON.

In Toronto, Weathering ran from January 18–21, 2024 at Daniels Spectrum and FACE RIDER ran from February 8–16, 2024 at Winchester Street Theatre.

Feature Image: From FACE RIDER, 2024 by Fran Chudnoff. Photo by Marlowe Porter courtesy of Blackwood Gallery.