Binds, belts, and blood: On Theodore Wan and Paul Wong at the Richmond Art Gallery

22 January 2025By Héloïse Auvray

A man, hovering naked above the ground, each limb roped to a pole spreading his body open, reads the Book of Ecclesiastes until the pain becomes unbearable. This photo-text work, titled Hornby Island (1975), by Theodore Wan sets the tone for the two-person exhibition, Unit Bruises: Theodore Wan & Paul Wong, 1975-1979 curated by Michael Dang and featured artworks by the two Chinese-Canadian conceptual artists. Standing in the octagonally-shaped room in the Richmond Art Gallery, the viewer cannot escape the consideration of the body as a subject of experimentation, as an art medium. Throughout the show, artists Wan and Wong turn the camera on themselves and explore the capabilities of self-portraiture, pushing their own physical and emotional limits––and ours, as viewers––to the extreme.

Untitled (Hornby Island Performance) (1975) was a pivotal work for Wan, at the early stage of his career. Simply titled after the location it took place in, the work concludes his BFA at UBC and marks off the start of Wan’s exploration of his body as an art medium. Conceptual art’s rejection of aesthetics and interrogations on the “social function of art” were ubiquitous notions throughout Wan’s art education. As art theorist Jon Bird summarized it, “learning via the photograph’s ambivalent status as both art object and teaching aid became a new mode of experiencing art.”1 The application of these two ideas to Wan’s new found interest for the body led him to approach self-portraiture through a medical lens.

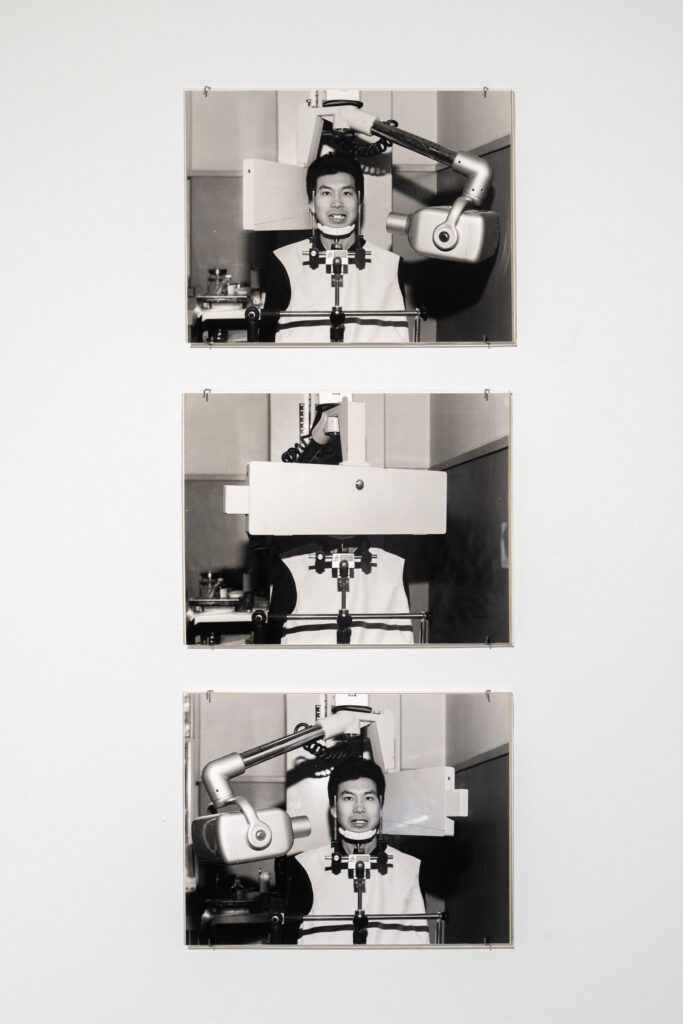

Indeed, the educational nature of medical imagery seems to shield it from the classical question of aesthetics. During his MFA at NSCAD, Wan benefited from a spectacular agreement with Dalhousie medical school, Halifax’s university of medicine: an access to the facilities of the college as well as support from the nursing staff in exchange of medical photography that would be used for teaching purposes. The photographic work provided went beyond the sole purpose of education. Wan stated the importance of accurately portraying the machines and their uses as well as the need for the body in the machine to be his.2 The works, while perfectly valid educational material, also doubled as self-portraiture. These polysemic artworks resulting from this trade perfectly inserted themselves in the conceptually-minded 1970s, where the re-evaluation of art’s purpose took hold. This sensibility would later be featured in Wan’s MFA graduating exhibition.

Despite this transition to medical photography, the theme of bondage and restraints seen in Hornby Island remained in Wan’s work. The body is kept tied but the ropes and knots from Hornby Island are here replaced by medical equipment, such as in Panoramic dental X-ray (1977), where the artist appears stiff, his arms restricted by a heavy, anti-radiation lead apron. He adorns a frozen smile, and his head is held still by a metal claw. Through the accurate fitting demonstration of these medical care procedures, Wan offers his body as a model for the prime subject—the medical machine—introducing the idea of submission to medical furniture and toying with body restraint.

This exploration is pushed further in the photo series, Bound by Everyday Necessities (1979) where Wan is represented in the Circ-O-lectric Stryker Frame Bed, an elaborate instrument first introduced in the 1950s meant to alleviate patients suffering from a spinal injury through the rotation of their body by keeping their spine maintained in place by splints. Some testimonies recall its humiliating quality, as patients would be unable to operate the device themselves if the nurse left the control button out of reach.3 When Wan created this series, the use of these therapeutic beds was already obsolete as they had been discredited for their inefficiency.4 The photographs, which were originally hung in Halifax’s Victoria General Hospital as outdated instructional images, question the authority of the medical staff’s knowledge and the authority of photography, both transient by nature. Now stripped of its efficacy, the Circ-O-Lectric can be seen as a tool of complete submission to the mechanical and medical authority, as represented in these photographs by real-life nurse Linda Mills, who stands beside Wan in the bed.

Now seen in an art gallery context, I couldn’t help but think about kink when viewing the series. Wan’s body rotated in this grotesque contraption at the mercy of a nurse sporting a skirted uniform could figure in a dusty fetish publication. Knowing this presentation is accurate to reality, an exact depiction of a medical practice, I investigated the possible similarities between medical care and kink relationships. The power dynamics between doctor/patient and dom/sub share the implied authority of the first and the consented submission of the latter. In theory, the authority figure—the dom or practitioner—knows what is good for their sub or patient and makes decisions for them. Discomfort and pain will be welcome or tolerated as long as the result is restorative. This understanding between the two parties can only be reached via trust and communication. The sub shares his desires and boundaries. The patient describes his pain and symptoms. Both must be heard and the respective dom/practitioner must act upon this information accordingly. Similarly to kink, where miscommunication or disregard of the others limits and needs can lead to abuse, medical care requires clear communication and consent to not result in malpractice.

With the problematic and complex power dynamics of the hospital in mind, Bound by Everyday Necessities simultaneously portrays the trust needed to confide your body to the other who we trust to heal and provide care, and the eerie possibility of forceful and nonconsensual positioning of bodies within a contraption meant to remove bodily autonomy and submission to an authoritarian condition of care. As an outsider, the viewer can’t assume if the contract is respected.

The presence of Wan’s body in this educational photo series also introduces race into the White-dominated world of medical documentation, which has historically led to severe misjudgements and oversights in treatments for racialized people within Western medicine. In the photo series, Bridine Scrub for General Surgery (1977), Wan captures his body painted by Bridine, a preoperative antiseptic solution. He followed medical illustrations found in Alexander’s Care Of The Patient In Surgery, showing the application patterns on the body of a white woman. Once again, these pieces were created as educational material. By making his Asian body the subject of Western medical practices’ educational documents, Wan presents a strong statement against a white-centered curriculum, demanding the same care and the same knowledge of his body as his white peers.5

Artist Paul Wong similarly uses his body, in a not-so medical but no-less subversive way. Where Theodore Wan stays away from the pain and alteration of the body, Wong throws himself whole into it. The following pieces introduce the body as a vessel of emotion and as a subject of weaponized voyeurism. Wong’s complete submission of his body to the point of pain opposes Wan’s static photographs depicting immobilized bodies .

On a tiny screen, a video shows Wong throwing himself against the walls of a room, his furious trance captured on five different video channels. This work, titled In ten sity (1978), is a performance that took place in a 8’ x 8’ x 8’ open cube––four walls and a padded floor, built inside of the Vancouver Art Gallery. The work was dedicated to Wong’s art partner and friend, Kenneth Fletcher, who committed suicide several months before the piece was made. For twenty minutes, Paul Wong endures a never-ending explosion of rage moshing against himself, throwing his body from wall to wall, attempting to climb out the space, and rolling around to a compilation of punk tracks drowned in an atmospheric droning noise. The four walls and floor are pierced by five cameras, which feed is transmitted in real time to the audience outside of the cube.6 This explosion of grief is utterly private yet scrutinized by the live witness of the performance in 1978, and now by us in 2024.

The recent tragedy of Wong’s loss of his friend Fletcher led viewers to worry about Wong’s wellbeing in the cube. During the original performance, members of the Mainstreeters, a Vancouver-based art gang active from 1972-1982 that Wong and Fletcher were a part of, began climbing the walls and participated in Wong’s fury, perhaps as a means to share his grief or interrupt the increasing intensity of his performance.

Wong’s video work is incredibly vulnerable. In the artist talk related to the exhibition, he mentions how the introduction of Sony’s Portapak, the first portable camescope available to the public, made video production more accessible.7 He saw the opportunity to use the video medium as a mirror, to turn the camera on himself. Wong’s objective of making his private grief public via video served as a portal into marginalized voices and experiences. Quite literally, the live-streamed video was the only thing allowing viewers to see what was happening in the privacy of the cube.

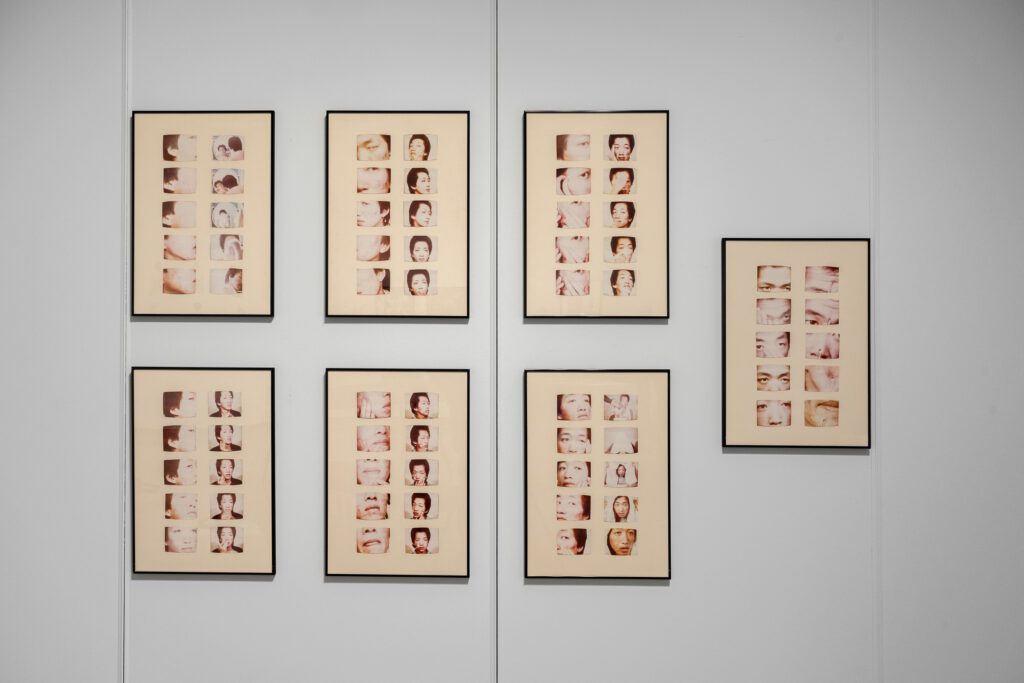

The artist continues this exploration of broadcasted privacy with the performance 7 day activity (1977). On screen, we see Wong scrutinizing his face, experimenting with different acne treatments from picking his skin to applying ointments. Such actions, deeply relatable for many, usually take place in the privacy of one’s bathroom. Yet these dermatological trials, voiced over by Wong’s inner monologue, are interrupted by medical information about his condition and sporadic comments or unsolicited advice from his peers. The artist expresses his difficulty to come to terms with his acne, a condition he believes strips him of his adulthood and masculinity.

7 Day Activity’s testimony of aesthetic struggle thinly veils the pressure imposed onto Wong to conform to white, societal expectations of beauty. In his artist talk, the artist explains how as a “pimply Chinese geeky outsider and counter cultural young man,” he was deemed not desirable. While acne can be a painful condition, most of its harm comes from the stigmas associated with it, such as being considered unhygienic, careless with nutrition, indulging in an unhealthy lifestyle––overall all results of negligence and not conforming to the expected social conduct of taking care of oneself. Advice such as “See a doctor for Valium” or “You have to watch what you eat” are heard proclaimed off-screen by some Mainstreeters. These suggestions point to internal and individual behavioral adjustment and don’t acknowledge how most of Wong’s hurt is of a systemic cause.

Throughout the video when Wong’s friends interject, “I never had anything that bad” or “It’s really not as bad as you make it to be,” I recall the video work Free, White and 21 by Howardena Pindell. In 1980, the artist filmed herself sharing gut-wrenching stories about the racism experienced first by her mother, and then herself, as Black women. Within the video, Pindell dresses up in whiteface and a blonde wig, where her white alter-ego calls her “paranoid,” “ungrateful,” and “replaceable”—echoing things she and her mother have heard throughout their lives. Similarly, in 7 Day Activity, Paul Wong weaves a metaphor of fruitless, unrecognized efforts in order to assimilate and follow arbitrary rules determined by the dominant white cultural beauty standards.

In 2022, a tape containing 60 Unit Bruises and 50/50 was digitized, which allowed for a resurfacing of these works, created by Paul Wong and Kenneth Fletcher, from the archives of Western Front. Wong then decided to compile these two works and created Blood Brother (1976/2024). The videos document the pair’s experiments with their bodies, exchanging blood and creating bruises via injections. In the 1970s, Wong and some of his peers recreationally experimented with injectable drugs. He describes sharing a needle as “one thing you [do] with only the most trusted people.” The intertwining of pain (by the needle), pleasure (through the high) and trust (shared with substance use companions) echoes the kinky qualities I’ve applied when thinking about Wan’s work. Blood Brother is a sensitive exploration of taboos surrounding the wilful creation of pain, the exchange of bodily fluids, and of consent in drug use, both recreationally and medically. Unlike in Bound by Everyday Necessities, there are no power relations at play, only equilateral, consensual experimentation. Fletcher and Wong care for one another after they draw and inject blood. Seeing the syringe, not in its medical environment but in an intimate space, used to inflict pain to the body for play and as a demonstration of love is subversive, and draws back to kink, where pain, care, and pleasure are intertwined.

To the contemporary viewer, Blood Brothers is an inconceivable piece of work. In the 1980s, a few years following the making of the performance, the AIDS epidemic shed death predominantly upon the LGBTQ2+ and POC communities. What initially was a demonstration of love and a radical act of bonding, now carries a much heavier meaning and tragic history. Richard Fung, when describing the piece, notes that “It evokes nostalgia for a present no longer possible.” The AIDS crisis went largely overlooked by authorities due to its found origin amongst LGBTQ2S+ groups. The epidemic had to be tackled by grieving and/or afflicted members of marginalized communities, caring for their peers and themselves while the government wilfully neglected their pleas and underfunded the research for a cure. Darkly prophetic of the times, Blood Brothers closes the show with the ultimate proof of the devastating effects of medical neglect on marginalized communities.

Fifty-years later, Theodore Wan and Paul Wong’s earnest and peculiar defiance of medical authority and racial oppression through depicting their bodies in explorative practices has proven its timelessness. The progress of medical imagery and recording devices such as cameras will always feed artists new ways to dig deeper and more accurately show what transpires from interacting with the world around us. This kind of visual documentation acts as a medium for introspection on the predominant societal systems and humanity’s sway between vulnerability and resilience. In this way, Unit Bruises is an exceptional demonstration of irreverence and proves that unapologetically showing marginalized Asian queer bodies will always be subversive.

- Jon Bird, Rewriting Conceptual Art, Ed. by Michael Newman and Jon Bird (London: Reaktion, 1999) 21.

- Christine Conley, Theodore Wan (Halifax: Dalhousie Art Gallery, 2003), Appendix B.

- Testimony found on reddit, see:r/scoliosis by u/ssenelgro, “Anyone take a ride in one of these? CircOlectric Syrker Bed” Reddit, September 7, 2023, https://www.reddit.com/r/scoliosis/comments/16cnn68/anyone_take_a_ride_in_one_of_these_circolectric/.

- Conley, App. B.

- Such social inequalities in healthcare still remain unresolved and further exclude people of colour, women, queer and gender nonconforming individuals. Medical practices are still riddled with sexist and racist stereotypes on pain tolerance, slut-shaming, botched diagnoses for fat individuals, ignorance about gender identity and so on… It is a complex problem that requires a restructuring of power and authority. Visibility and the inclusion of non-white and non-male subjects within the corpus of educational documents is a fundamental stride.

- Paul Wong, “In Ten Sity,” accessed January 11, 2025, https://paulwongprojects.com/portfolio/in-ten-sity/.

- Paul Wong, “Unit Bruises: Paul Wong and Michael Dang in Conversation” moderated by Michael Dang, artist talk, May 25, 2024, posted June 6, 2024. Richmond Art Gallery, YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dGHuzjyYFqw.

- Wong, “Unit Bruises: Paul Wong and Michael Dang in Conversation.”

- Paul Wong, “60 unit; Bruise,” accessed January 11, 2025, https://paulwongprojects.com/portfolio/60-unit-bruise/.

- Jack Lowery, It Was Vulgar & It Was Beautiful: How AIDS Activists Used Art to Fight a Pandemic (New York: Bold Type Books: 2022).

Unit Bruises: Theodore Wan & Paul Wong, 1975-1979 was curated by Michael Dang and ran from April 20 – June 30, 2024 at the Richmond Art Gallery in Richmond, BC.

Feature Image: 7 Day Activity, 1977, by Paul Wong. Photo by Michael Love courtesy of Paul Wong Projects and Richmond Art Gallery.