consciously incoherent: anti-aesthetics & associational networks in ‘fractured horizon—a view from the body’

15 June 2021

By Zach Pearl

The poignance of an exhibition is often measured by its ability to distil a historical moment, letting it hang in the air like luminous vapour. Amongst the media art exhibitions of the last year, perhaps none were more poignant than the eight-part artist video series, fractured horizon — a view from the body, which circulated during the weeks of protest that followed the killing of George Floyd. Curated by Toronto-based curator and editor Yaniya Lee as the culmination of her research residency at Vtape, Canada’s largest video art distributor, an impressive range of works by BIPOC women artists from Canada and the United States were sent out to Vtape subscribers’ inboxes like supplements; weekly injections of perspective and affirmation for all those in the arts community already feeling disheartened amidst the first wave of a global pandemic, and one now imbued with the urgent politics of fighting anti-Black racism and revealing white privilege. Like a shot in the arm, every Friday between June 5th and July 24th, 2020, a new piece would go up on Vtape.org, sometimes elegiac in tone, sometimes documentarian, but all of them anchored in their conjuring of the body politic. Pieces by Buseje Bailey, Richelle Bear Hat, Hannah Black, Deanna Bowen, Thirza Cuthand, Cheryl Dunye, Donna James and ariella tai each, in their own way, worked to reaffirm the vital connection between the social and material factors that constitute a “body” in the contemporary moment and, more specifically, to interrogate the strategies of representation that keep existing power structures in place.

In Buseje Bailey’s BLOOD (1992), for instance, the artist lathers her hair in the shower in an intensely slow and pixelated performance where her face seems tactically obscured, her scalp and arms the only discernible features. This oblique aesthetic treatment renders her body as an abstraction, a kind of digital sculpture of the figure moving in slow motion, and the sense emerges that Bailey wants us to look at her body, but not necessarily to recognize her, to see her specifically. In foregrounding her material presence while obscuring its details, Bailey’s work presents her body as a surface that simultaneously invites and resists interpretation; a gesture of protest as much as it is a siren song for our gaze.

A similar sensation emerges when viewing Cheryl Dunye’s Janine (1990), where the Liberian-American artist recounts a high school friend’s blindness to her own white privilege and homophobia as they came of age together in Philadelphia. In contrast to Bailey, Dunye’s body is extremely legible. She looks directly into the camera, giving her frank account. However, even as Dunye’s visage fills the screen, taking up space and pronouncing her own lived experience as a Black queer woman in a dominantly white school system, her image is interrupted by slow-zooming close-ups of the young Janine, smiling serenely and ostensibly oblivious to the micro-aggressions she’s committed. Even as Dunye’s voice resounds with agency and honesty, her image is temporarily replaced, subsumed by one of whiteness—a reminder that in this work, Janine is not a person per se, but a cipher for all those instances of power asymmetry that fracture society and consequently manifest in visual culture.

One of the most notable aspects of fractured horizon is its variety of formal approaches, evidenced by the drastically different aesthetics of these pieces. The heterogeneity is so great that the program would have a hard time cohering as a visual statement in a physical gallery space. But in their virtual and subsequently visual fragmentation, the ethical and political dimensions of each work was foregrounded in this articulated presentation. And the program took on greater significance for its motley aesthetics, giving way to an emphasis on interpretation and interaction. This was especially vivid in the far more intimate context of the individual user watching the program from their bedroom or kitchen table. Anecdotally, it became hard not to gauge oneself as another ‘body in the room’ when viewing any of the artworks. That meant the visceral discomfort of hearing a queer Indigenous person describe being discriminated against as a child while the camera zooms in on their skin, close enough to render pores, as in Thirza Cuthand Is an Indian Within the Meaning of the Indian Act (2017). ‘Listening in’ on generational knowledge as it’s tenderly passed down by Afro-Caribbean aunties whose faces are never seen, as in the case of Maigre Dog by Donna James (1990), produced a dysphoric sense of hovering outside the looking glass, a bit like the Ghost of Christmas Past. In this way, the political subtexts of the works intervened and affected the homes and personal spaces of viewers in a way that was completely unanticipated when Lee first envisioned the program. But the need to exhibit them online ultimately imbued the series with a sense of proximity and immediacy that would have been lacking had the screening gone on as planned in a public setting. Intense moments of honesty or vulnerability in the works benefitted from the informal nature of the virtual viewing space, and this became a significant interpretive factor in experiencing them as a collection.

Such moments that re-place emphasis on the conditions of viewing as constitutive of the aesthetic experience, speak to the disappearing line between ethics and aesthetics in contemporary art—what Hal Foster and, later, Heather Kerr have called the “anti-aesthetic.”1 Under this concept, the motivation behind a visual work is more than the realization of an image-object, rather it is a site that operates as an allegorical vehicle for critical empathy by way of imag(in)ing an ‘other’ beyond the viewer’s subject position in the act of interpretation. In other words, there are no expectations of visual splendour or even ‘good-looking’ art under the sign of the anti-aesthetic, because the concept of aesthetics in this context is of an affective, metaphysical nature that exceeds traditional rubrics of medium, method or style. In this way, anti-aesthetic artworks refuse to be consumed passively as ‘purely’ aesthetic creations and require a deeper level of engagement with the ethical implications of their creation. This ethico-aesthetic sensitivity holds true for each of the works in fractured horizon, insofar as the artist’s own marginalized identity (often the image of their own body) not only comprises the subject matter of the piece, but the conceptual fulcrum on which it turns. Engaging the program as a whole can best be summed up by a sense of rapid oscillation on this fulcrum—between the aesthetic and the ethical; a tension that pivots on knowing its affective paradoxes are designed and deliberate.

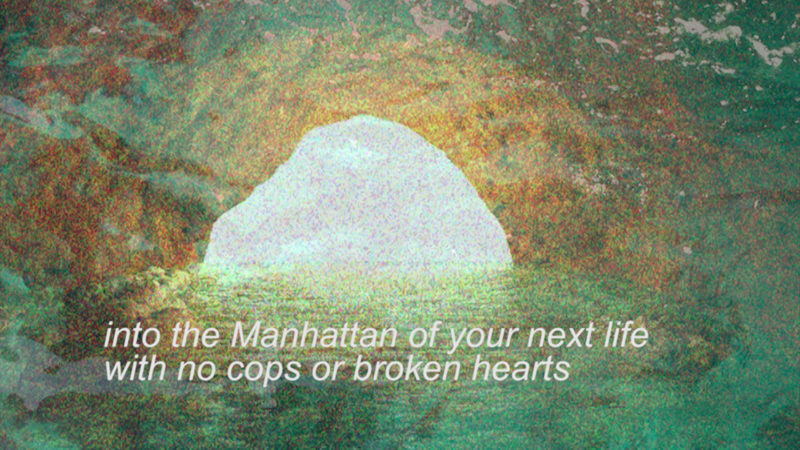

In Hannah Black’s My Bodies (2014), we encounter dissected images of middle-aged white men’s bodies—their hands, eyes and teeth—against a mashup of Black female musicians singing, speaking and rapping the words “my body” in robotic succession. The conceptual tension is compounded by the rapid oscillation of the imagery to the sound. Here, the viewer is like a flame in open wind—flickering about between different signifiers and stimuli to dizzying effect. Towards the end of the piece, the sequence pauses on a solarized photograph of a watery cave opening. Beyond it is a field of pure white light, and text beneath appears like subtitles, describing the sensation of passing through the light “into the Manhattan of your next life with no cops or broken hearts” (2:21-2:50). Whose next life are we speaking of? Are we the body passing into Manhattan? Is this a singular body, or a collective one? The aporia of the bodiless transcendence in Black’s piece suggests a body is always more than one thing, or one form—plural and polysemous—and that bodies are implicated in every act of communication, whether depicted or not. Sensing this and reckoning with it, however, is not something that comes easily without a face, a hand, a hairdo, or a skin colour to scaffold our conventional interpretations. But this is the nebulous and ethical viewing space of fractured horizon, and its anti-aesthetic form and viewer.

Consequently, the anti-aesthetic viewer is always hard at work to discern their orientation, constantly navigating various subject positions. However, in Sara Ahmed’s aesthetically-informed political theory of “queer phenomenology,” she suggests embracing this modality of disorientation, arguing that a failure to keep moving or to move ‘correctly’ from one position to another can yield self-realization and social value in its own right:

“If we think with and through orientation we might allow the moments of disorientation to gather, almost as if they are bodies around a different table.”2

We can take from this the possibility that failing to orient, to identify, failure to keep moving from one definite ethical or political stance to another but lingering in the fray and heuristically ‘seeing what happens,’ is a stark but no less viable approach to more sensitively and pragmatically navigating the world.

In thinking through fractured horizon as a networked body of dis-oriented pieces—Donna Haraway’s germinal conception of the cyborg rears its infamous (non)head. This is not because of the expected and tired ways in which Haraway’s cybernetics have been used as a prop or a distraction in so many undergraduate essays, but because she herself articulates the nomadism of the cyborg body as the fluidity of communication itself:

“The cyborg is text, machine, body, and metaphor—all theorized and engaged in practice in terms of communications.”3

In other words, there is no cyborg body without continual interaction, disorientation and feedback to sustain a continual process of adaptation and re-invention. In her more recent elucidations of cyber-ecofeminist politics, Haraway theorizes what it would take to “make kin” with other species in this cybernetic fashion in moments of imminent mutual benefit; to become compost with the world.4 While radical-kinship-as-compost may ring esoteric for most, it serves to perfectly capture the type of body politic at work in “fractured horizon”: A body (of works) only unified by time and space, saturating the perception of one another in subtle and insipid ways; breaking each other’s borders in their collective viewing. This particular effect cannot be accomplished by viewing the works in isolation, only in their collaborative constellation.

In this regard, fractured horizon delivers on its titular premise as a ‘broken’ thing—a fractured body but a working assemblage. Even the most stylistically divergent pieces share a productive tension in their arrangement. This is perhaps clearest when moving between Deanna Bowen’s sum of the parts: what can be named (2010) and Richelle Bear Hat’s In Her Care (2017):

Bowen’s piece distinguishes itself in its dramaturgical tone. Orating historical research of her African family bloodline from the time of their enslavement and deportation to the U.S. and their subsequent migration to Canada, Bowen, set against a pitch-black background, reads to the camera from a large notebook, taking measured breaks to look up from the text and gaze intently at the viewer. These outward glances are more than acknowledgements of a witness, however, as the precarity of the camera work—its oscillation between jittery pans and short bursts of erratic zooming—butt jarringly up against moments of deadpan, rock-steady focus. One moment, Bowen is speaking of her past statistically—purely in the language of ‘objective’ history—then abruptly, anecdotally, with feeling and reflection. Illustrative of the networked body, Bowen enacts her family history as a series of components, bits and pieces of information that she is fully aware can only convey so much. A name and a date of birth are hardly substantial in and of themselves. The puniness of “sum” in the work’s title betrays that Bowen is acutely conscious of the irresolvable gap between objective ‘facts’ and subjective knowledge, especially when regarding generational trauma. Differences in typography within the video also appeared to formally reinforce such gaps. As Bowen introduces new family members from her tree, their names are displayed as subtitles in the lower-right corner of the frame. However, not all names and time periods are treated in the same way typographically. Those family names that predate the 1960s appear in calligraphic script font versus those after 1966, which appear in monospace, indicative of digital technologies. Those family names closer to ‘home’ and to Bowen’s own lifetime return to a hand-scrawled script font, as if to signal graphically that the content of the narrative is becoming more intimate—indexical of the human hand. In any case, Bowen’s performance is calculated, rehearsed; her face communicates a grave sincerity that is both theatrical and confessional. In the calculated mixing of registers between the personal and political, Bowen’s video unsettles the generic boundaries of documentary, autobiography and the imaginative potential of theatre.

In complete aesthetic contrast but no less affecting, Richelle Bear Hat’s video work In Her Care (2017) is quiet, consistent and indirect. Never fully appearing in frame, Bear Hat speaks in a voiceover about the role her mother played in demonstrating how to nurture and care for the land around her. Her tone is soft and steady as shots of vistas from her native Treaty 7 territory (near Calgary) linger for several seconds, sometimes the better part of a minute: prairie grasses and wildflowers bow in the wind; a distant truck rounds the bend; we watch a parking lot of a community centre as it fills with cars on a cloudy morning. Throughout, one wonders if there will be a climax to the layering of these vignettes—a moment when the pace of the imagery might change, or the volume and cadence of Bear Hat’s voice might shift. But nothing about the video intensifies across the nine minutes of playback. Rather, the measured temperament of In Her Care comprises its intensity, like a singer sustaining a low but stirring note. The simple acts in which the artist’s body at least partially enters the frame take on greater significance as subtle ‘crescendos’ in an otherwise homeostatic progression of vistas. In particular, a scene of Bear Hat’s hands descending from above to weave stems of field grass into a braid, and another where she lies down in the grass until no longer visible, as if melding with the land, anticipate a reaction or a resolve that never arrives, foregrounding the impermanence of these gestures and the ‘soft power’ that results from enduring them.

Viewing In Her Care both temporally and spatially right before sum of the parts produces an impressive concatenation of anti-aesthetic moments. This sensation is repeated with each new piece in the program; a visceral juxtaposition that fights against the very notion of a unified screening program. In their pragmatism and specificity, the works of fractured horizon do not sit comfortably together so much as offset one another, and while this is perhaps the greatest weakness of the screening series it can also be seen as its strength. From an anti-aesthetic stance, the beauty of fractured horizon is its refusal to be apprehended as a unified ‘body.’ Certainly, when viewed as a linear program, in the order that the works are positioned in the layout of the webpage that situates them (vertically stacked, scrolling downward), there’s little in the way of visual connection, but this, in fact, also warrants reflective pause and not passive consumption.

Could it be that the somewhat disjointed nature of Lee’s program is also an intentional curatorial strategy, much like the networked and dis-oriented body politic of the works within it?

Each of the works in the series operates in some ways to curb interpretation, or at least the notion that any concrete meaning can be gleaned. If the works are, as I propose, as much ethical propositions as they are formal and visual compositions, then perhaps the ‘brokenness’ of their presentation is a reflection of this very notion of uncertainty. Put another way, fractured horizon is a gambit to complicate, even frustrate its very reading. But why do this? Does a curated program have an obligation to be cohesive or even coherent?

As a closing thought, it’s helpful to ruminate on the above question by first reconsidering fractured horizon and exhibitions, more generally, as a form of writing in the larger writing space of our mediascape.5 In this convergent (hyper)reality, the curated video art program is also a kind of text. And typically, a curated text renders a legible thesis or argument. However, in the case of fractured horizon, the reading of the text feels too evasive for argument. It too, like the artworks, is distributed and fractured. This is precisely because the kind of writing seen in fractured horizon is association-driven—the process replaces the product….6 In this light, navigating the screening also means abandoning the notion of a through-line in favour of contemplating what media theorist Gregory L. Ulmer calls “associational networks,” where the movement of the reader/viewer/user is erratic and happenstance by design. Associational networks operate on a logic of imminence (as in proximity) and this in turn becomes a form of empowering the invention of new connections and new forms of meaning. In this sense, “invention” embodies the ongoing task of site-specific re-presentation and reclamation.

Brief moments of productive conflict arise from coming into immediate contact with others, into association and thus invention, and in this imminent territory of experience, the ethical and the aesthetic ‘overlap.’ But by the same virtue, associational networks are forever fuzzy bodies. In their between-ness, they fail (again, by design) to offer answers or assuage moments of friction. As unsatisfying as this may be in our current techno-scientific times, it’s important to recognize that this kind of urge for determinism is a colonial and primarily white Eurocentric manner of engaging the world. Alternatively, the networked logic of fractured horizon forces us to leave room in the record, and to make space, in Ahmed’s words, “around a different table,”7 for the possibility of perpetual uncertainty. Today, amid a global pandemic and a tumultuous political landscape, such a consciously incoherent view—a view from the body—is increasingly necessary in parsing the fictive mediascape, reading all texts between the proverbial lines, and making those fractured, yet crucially situational, intersubjective connections.

- See both Hal Foster. “Introduction.” The Anti-Aesthetic: Essays on Postmodern Culture. Hal Foster, Ed. New York: The New Press, 1998, ix–xvii. And Heather Kerr, “Fictocritical Empathy and the Work of Mourning.” Cultural Studies Review, vol. 9, no. 1, 2003, 180-200.

- Sara Ahmed. Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others. Duke University Press, 2006, 24.

- Donna Haraway. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature. New York: Routledge, 1991, 212.

- See Chapters 3 and 4 in Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016, 58-103.

- Jay David Bolter. Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext, and the Remediation of Print. Second Edition. Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers, 2001.

- Gregory L. Ulmer. Heuretics: The Logic of Invention. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1994, 38.

- Ahmed, 24.

fractured horizon — a view from the body ran from June 5 – July 24, 2020 online at Vtape in Toronto, ON.

Feature Image: she’s not gonna get more dead, 2018 by ariella tai. Video still courtesy of Vtape.