Contorting Ourselves to Appease Them All: Alexa Hawksworth’s Semi-Detached New Build at Projet Pangée

9 August 2022

By Kate Kolberg

You’re sitting, reading in a cafe. Your brain announces to itself: “I’m a reader,” as if somehow that makes you virtuous. In theory, the book’s subject is interesting, but if you’re honest with yourself, you’re struggling to get through a single page, let alone internalize the information being presented to you. Instead, apprehension floods your brain: Am I comfortable or too caffeinated? Do people think I look smart? Maybe I seem mysterious or, maybe, just pretentious. Wait, do I even like reading? This dizzying relationship the self can have to the self—often seemingly innocuous yet fundamentally fraught—was the subject of much of Montreal-based painter Alexa Hawksworth’s work in her recent exhibition Semi-Detached New Build at Projet Pangée. Through an ad-hoc assembly of caricatures and scenes, Hawksworth’s paintings explore the relationship we have with ourselves: the non-negotiable correspondence that is ever-vulnerable to context, doubt, timing, and, perhaps most importantly, our perception of how we are being understood by others.

In her own words, Hawksworth’s practice is a study of “the tension between a rigid identity that has a representational form and the fluidity of life that always escapes these identities.” Defined as “the fact of being who or what a person or thing is,”1 identity could easily be seen as a grandiose subject, but Hawksworth approaches it humbly, quietly toiling over age-old questions concerning the true applicability of the singularity and distinctiveness of this “fact” and how such a “fact” might be visually represented. Abundantly apparent throughout the exhibition is how Hawksworth benefits from her acute and agile sense of figurative painting techniques, smoothly blending references from visual cultures that range from art history—including painters like Edvard Munch, Ferdinand Hodler, or American Realists such as Grant Wood, Jared French and George Tooker—to films like John Cassavettes’ A Woman Under the Influence (1974). Hawksworth crafts layered, fluctuating narratives that hint at the organized chaos that is attempting to understand, represent and perform ourselves in the shifting context of others and their perceptions.

Hawksworth veers toward scenes that are falling apart or collapsing, and works like Interior Night I (2021) articulate this clash very plainly. In this piece, along with one other in the show, a central painting is encompassed by a wide pine board frame (not unlike an oversized picture frame matboard) that has been painted in its own right. In Interior Night I, the centre painting depicts a figure reading a book with a pleasant look on their face. The reader looks at ease and seems oblivious to the fact that on all sides they are framed by a frenzied swarm of terror-stricken individuals struggling to flee a hellish landscape of green flames. In the end, the exact imagery of the two scenes is almost irrelevant, as what’s really on display is the antithetical relationship between them. These encircling frames work to tacitly imply how the process of putting something, anything, forward is inherently fraught by its context. Take the oblivious reader, for example; they appear content, yet, on some level they are aware of what reading signifies in their social context and may, in fact, be doing so in order to acquire particular accolades or to have others perceive them in a certain way. Read like this, the hellscape begins to look like a blunt arrayal of how our attempts at control usually fail—whether that control be over our image as the virtuous reader or otherwise.

This is not meant as a wide-scale critique of people on Hawksworth’s part though. Rather, she is foregrounding how vulnerable a person’s identity is to confusion, chance and context and how, as individuals, we get caught up in an entanglement of perceptions (coming from the self, others, expectations, anticipations, etc.) as we try to contort ourselves, whether consciously or unconsciously, in the attempt of appeasing them all. Her paintings confess an air of abjection toward the self, though they refrain from a full embrace of the horror or revulsion, looking instead to foster a landscape of ambiguity. The happy reader loves themselves while hating themselves; they laugh at themselves but take themselves too seriously; they are a labyrinth of contradictions, which, fortunately-unfortunately for said reader, they are all too painfully aware of.

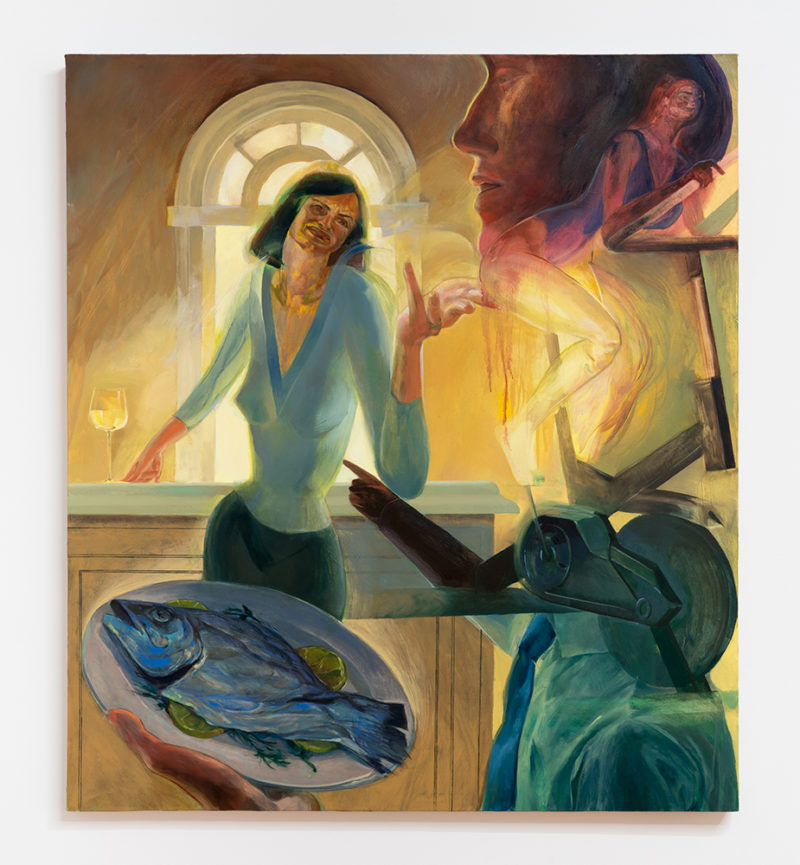

As mediums built on showcasing the interdependent nature of emotional expression, film and theatrical performance are some of the tools Hawksworth uses to think through this entangled landscape of identity. In particular, Hawksworth looks to the films of John Cassavetes, admiring his presentation of actors as always in flux. As an example, she offers how the character of Mabel Longhetti in A Woman Under the Influence (played by Gena Rowland) displays not only a “very honest portrait of a woman who seems to be deeply conflicted by all the different identities she has to try and fit into (mother, daughter, wife)” but one that “really shows the breakdown as she struggles to move between these states.”2 This description of Rowland’s conflict makes me think of Hawksworth’s painting Eggbeater (2021).

Eggbeater illustrates a scene of a woman with a glass of white wine beside her as she gestures frustration or anger toward the disembodied, expressionless head of a man who holds a plate of nicely prepared fish. Superimposed over this scene, the same woman rides an exercise bike and the man, pictured only as a body in button-up shirt and tie, points a finger at her accusingly. In this particular work, the female strikes me as the protagonist. The male gaze, or rather the lack thereof, foregrounds a sense of her emotional isolation in the narrative of their marriage as she acts out the socially sanctioned image of a “good” upper-class housewife. You can almost hear her asking: “I’m doing everything I’m supposed to, so why am I so unhappy?” In her layering of subject matter and portrayal of motion, Hawksworth establishes visual representations of time and the shifting of perception. The suggested argument here is not intended to picture an isolated event, but rather a pervasive, muddled feeling created through compounded arguments that are in the process of bleeding into who they are becoming—to themselves and to each other.

Film and theatre further guide Hawksworth’s thinking around the artificiality of art. Informed by German playwright Bertolt Brecht’s concept of the estrangement effect3—or an artist’s organized use of mechanisms that force an audience to grapple with the fact that they are witnessing something artificial—she explained to me that she’s looking to not only foster but accentuate the distance between the viewer and the artwork. Hawksworth wants to remind the viewer again and again that it is just a painting and not some attempt at conveying something “real” (at least insofar as we typically classify observable phenomena). I think the distinction here is between paintings-as-fabrication (as in inherently fictional) and paintings-as-representation (as in depictions of events that either took place or been manufactured to appear as though they did). To Hawksworth, attempts at the latter feel more deceptive because they disregard the qualities of a moment or scene that are not strictly visual. In lieu of the actor’s tools of tone, gesture or emotion, Hawksworth uses painterly and compositional techniques to accentuate a scene’s artificiality.

This presents itself in Hawksworth’s work in two key ways. The first is in her use of layering. In nearly every work Hawksworth creates, narrative scenes and isolated imagery are piled one on top of the other, taking residence everywhere from the underpainting to the foreground. The layering is often so elaborate and nuanced that only during a prolonged look is the viewer able to find all the subjects or faces camouflaged within. The second key aspect of this visual language is the sense of movement, which sees subjects depicted in iterative states of flow or metamorphosis, or simply as shadowy blurs. A straightforward example of this appears in the pastel drawing done directly onto the wall of Projet Pangée, Canter (2021), which shows a figure as they morph from dog to human in a continuous, Animorphs-like progression. Circular and counterintuitive as it may be, Hawksworth gestures toward a more accurate and “truthful” representation are achieved through fostering a sense of distance, since it is this distance that allows the viewer to be open and objective to the numerous and sometimes incongruent iterations of her painting’s subjects.

Rather than try to figure out what exactly these iterations actually represent, I realize I should take a lesson from the undoing of Cassavettes’ Mabel Longhetti. To set fixed boundaries on how I perceive the “subject” may well only serve to further their own internal dilemmas of identity. This is what I see as the unique strength of Hawksworth’s practice. Beyond the specific content of the paintings, it is Hawksworth’s technique—the lines, blurs, dashes and layers—that actually disclose her core message: to embrace the inevitability of incompleteness. In their attempt to give shape to how it feels to be in a moment, these painterly gestures concede their very nature as attempts. They reinforce how an attempt is often the best we can hope for in our efforts to define ourselves amidst a sea of contexts and perceptions imposed on us both independently and externally. Through laying bare this vulnerable, often awkward and internalized space of self-contemplation—rife with doubt and confusion and always subject to new perspectives, contexts and change—I now see Hawksworth’s practice as an invitation to nurture a little more compassion and levity in how we relate to ourselves, and how we can better shoulder the ultimately unknowable burden that is the perception of others.

- Oxford Lexico. (n.d.). Lexico.com. Retrieved April 2022 from https://www.lexico.com/definition/identity

- From a conversation with the artist.

- Frederic Jameson, Brecht and Method, 1998. (London: Verso), 38-40.

Semi-Detached New Build ran from November 13 – December 18, 2021 at Projet Pangée in Montréal, QC.

Feature Image: Installation view of Canter, 2021 by Alexa Hawkswoth. Photo by Jean-Michael Seminaro courtesy of Projet Pangée.