DIY Karma Kit: Adam Revington at Support

20 February 2019

By Brennan Kelly

They’re all turned away; faces pressed against the wall. The wood frames circumscribing their borders evince this rotational reversal, displaying the typically undisplayed—incidental flecks of paint, v-nails clasping mitred joints, hardware insets, and vacant nail holes. Despite their reversed orientation, each frame is still performing its principal function, framing (and thereby demarcating) a discrete composition. In this dualistic state of front-and-yet-also-back, a question arises: Are these works, as individuated units of frame and composition, exposing something previously concealed? Or are the frames themselves merely turned away?

This Janusian quandary prefaces the first works encountered in Adam Revington’s solo exhibition, DIY Karma Kit, held at Support in London, Ontario. Seven collages span the longest wall of the space, each one set within an overturned frame that exposes its back to the viewer. This reversal appears both elementary and enigmatic, imbuing Revington’s collages with a peculiar resonance. In a display context, wall works are presumed to be non-Janusian, and consequently the desire to view what is hidden opposite a work’s outward face is typically null. But when the front of a frame is concealed the inversion is difficult to overlook, and the usual assurance—that nothing of interest is on the other side—rears with uncertainty. The reversed frames surrounding Revington’s collages destabilize the notion that these works are exclusively mono-faceted; instead, they oscillate between their antipodal faces, never quite settling on one or the other. From this perceptual dualism arises the temptation to turn the frames and glimpse what is concealed against the wall, if anything.

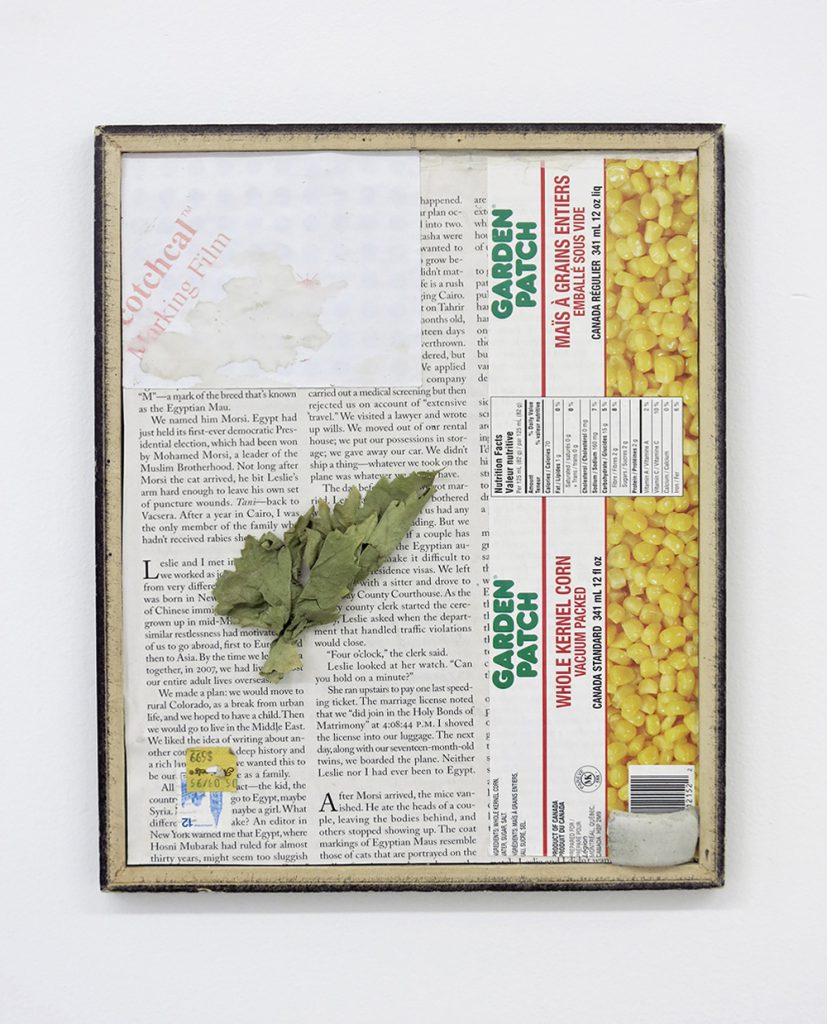

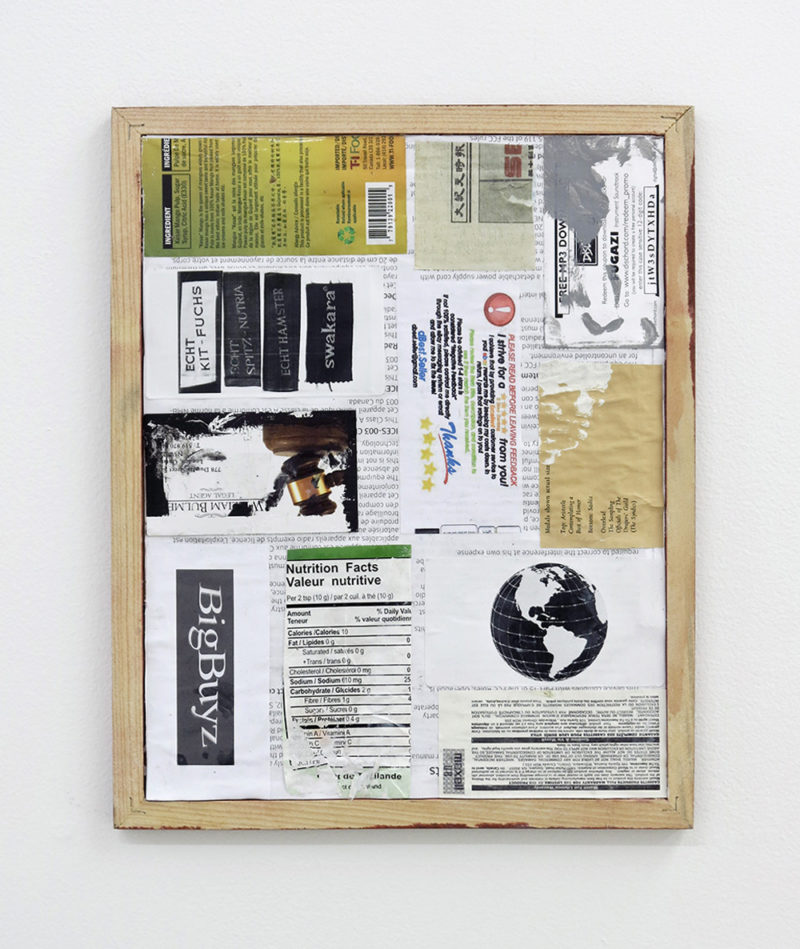

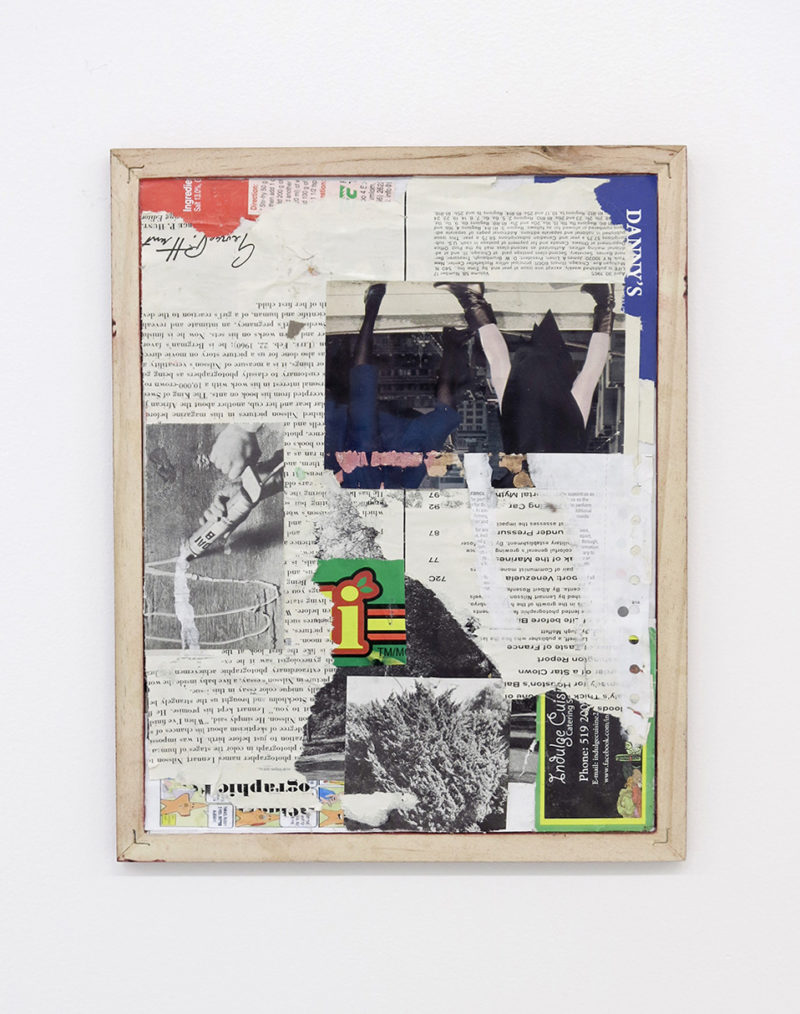

Haptic temptations aside, the collages’ viewable faces bare an array of dislocated texts/images, ATM slips, canned food labels, price tags, sticky-dots, and the occasional non-paper thing, all amassed into something akin to seven pages pulled from the scrapbook of a fevered dreamer. Torn residuals and elements partially buried behind proceeding layers suggest that the collages are caught in a moment of scrappy resolve, that they may be reworked in perpetuity; a never-ending process of addition and subtraction that parallels their orientational oscillation.

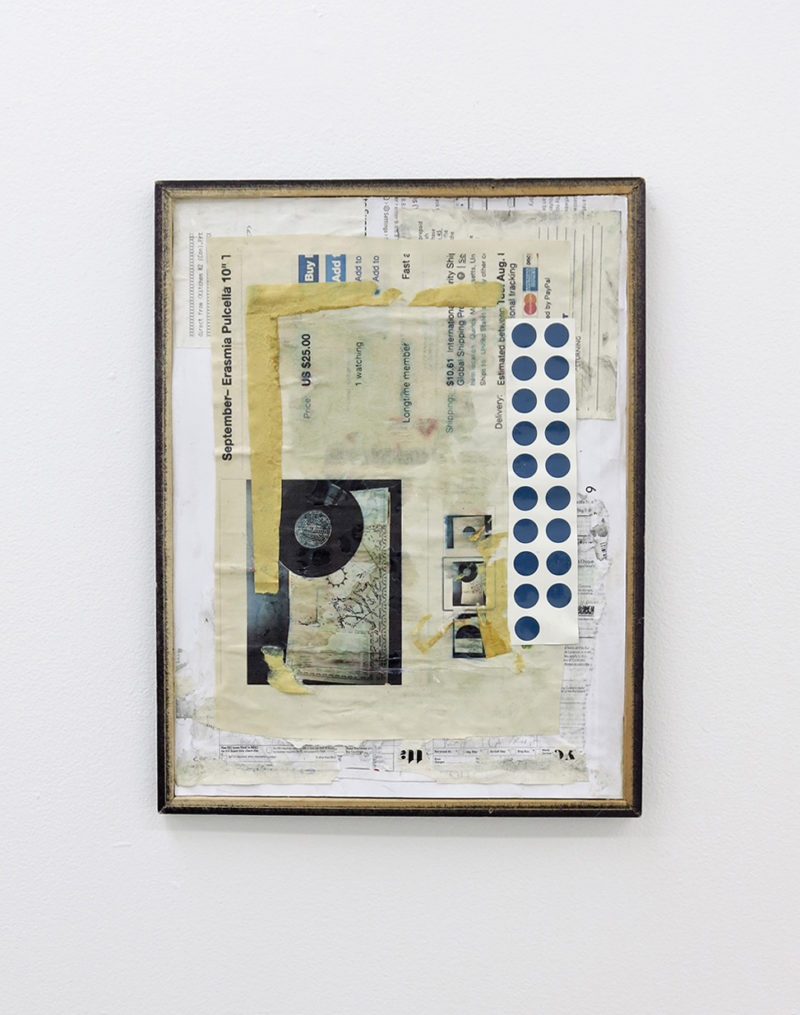

Gleaning the subtly intimated conceptual underpinnings of Revington’s collages is an exercise in careful looking—but this is not necessarily a detriment to the work, since an uninterpreted fever dream still remains an experiential phantasmagoria. It does mean, however, that these works operate as both phantasms of their own frenetic immediacy and languid revelations. Nevertheless, Revington’s video contribution to the exhibition, installed in the basement of the space, acts as an additional lodestar for the works upstairs (more on that later). In the absence of this video, one of the more forthcoming intimations can be found in Erasmia Pulcella (2018). Prominently displayed in the centre of this collage is a printed eBay listing for an EP of the same name by September, an obscure mid-90’s emo act. (1) At the time of this record’s release, eBay would’ve been a prominent Internet presence on the brink of mass popularity. The website’s auction-style premise has long since lost its novelty appeal and, enshrouded in the shadow cast by Amazon, eBay now operates as the Internet’s premier flea market. And who tends to scour through flea market offerings with more regularity than those individuals described as collectors?

Revington’s collages allude to the accumulated compulsions of such a collector, albeit one with ambiguous taste in objects. Aside from the EP’s transactional marker and the occasional postage stamp, many of the elements within the works signify the act of collecting via its adjunct materiality instead of its designated objectives. In HB (2018) an eBay vendor’s tag cautions the buyer that anything less than a five-star rating will be considered negative feedback, which is followed with a viscid profession that the buyer’s satisfaction is the vendor’s primary concern. Below this tag is a black silhouetted globe and another clipping that simply reads BigBuyz; the schlocky pictorial quality of both suggest similar eBay origins. Other elements, like the label from a can of water chestnuts in North Island (2018) and many of the mostly-upside-down fragments in Danny’s (2018), are less likely to produce associations related to the act of collecting. Nevertheless, these elements, much like eBay vendor tags, have a similar relationship to the consumer objects they are derived from. They are the detritus of consumption; the stuff swirling around commodity stuff.

Stuff, as an uncategorized and devalued mass of objects, could be considered antithetical to a collection, which in relation to a singular collecting body (biological or otherwise), evokes a systematically categorized and valued set of objects. In The System of Objects, Baudrillard makes a two-fold claim: that collected objects must be divested of their utilitarian function in order to be fully possessed, and that once possessed, they become equivalent with each other via the act of possession. (2) The boundaries between objects within a collection lose fidelity, allowing them to amalgamate into a collectivity that subsequently engulfs the collector, so that the collection defines, extends, and finally reflects the collector’s subjectivity. Revington’s collages propose an altered version of Baudrillard’s claim, that a divestment of value might be prioritized and that this absolvement predicates the inclination to collect. This results in a flattening, wherein all objects are already considered equivalent, causing the fidelity of the collection as a totality to spill out and engulf any and all objects without discernment.

What Revington appears to be scrutinizing with these works is the manifold desires and value systems driving the collecting impulse. Herein, the appearance of the vinyl record in Erasmia Pulchella takes on a dual meaning, representing itself as a commonly collected object, but also as a record: an object constituting a temporal occurrence. If the collection reflects the subjectivity of its collector, it subsequently exists as a record of the collector’s time vis-a-vis its productive allocation. Time is, after all, an integral aspect of collecting, not merely because it’s an activity that progresses gradually over time, but for the distinct manner in which time affects objects. The first of which is the notion of temporal resonance, that an object is considered a material representative of its time, thereby facilitating a cognitive slip between the past and present. While this resonance bestows an object with value for the collector, the second fundamental way in which time affects objects tends to do the opposite. This is of course, the problem of time—that it eventually wears even the most resolute materials thin. The responsive action to mitigate this problem is conservation, which results in a unique temporal disjunction: collections tend to outlive their collectors.

Instead of conserving the elements within his collages, Revington emphasizes their finite temporality, as if to narrow the entropic disparity between the body of the collector and the body of the collection. The solitary leaf in Garden Patch (2018) is dry and withered; the surface accretions of paper throughout the works are yellowed, torn, and undulating with glue blisters. And set as they are in the backs of their frames, the collages are not sealed behind a pane of glass. The deleterious effects of time, as mild as they may be in an exhibition space, are not to be deferred. While viewing Revington’s collages you can imagine their patchwork skin continuing to yellow, peeling away and eventually crumbling to dust. An inevitable march towards decomposition set in stride with that of the collector’s.

If there’s a feeling of steady dissolution in Revington’s collages, then his sculpture, Souvenirs (2018), offers the opposite: sudden exhumation. The small-scale work consists of four toy cars caked with dirt on a white shelf. Reconciling the work’s title with its material reality, these earthy extractions don’t appear to have arrived from a physical elsewhere, but rather a temporal one. Like resurfaced memories laid bare but distorted by the synaptic grime accumulated between their occurrence and remembrance. An outwardly more comprehensible collection than Revington’s collages, the toy cars allude to childhood and the collecting impulse bracketing its progression. It’s not uncommon for children, albeit predominantly boys, to become enthralled with cars and engage in collecting representations thereof. Prevailing media portrayals of cars depict them as machinic avatars of speed, power, freedom; the inverse realities of childhood make cars a conspicuous substratum for projective fantasies. Souvenirs may be a precursive collection to the one both present and intimated to in Revington’s collages, an embodied glimpse of a prior subjectivity perceived here as equal measure nostalgic reverie and soiled recollection.

In Support’s compact basement, Revington has installed a sculpture comprised of two bicycles leaning against the wall (The beautiful man is a cow, 2018) and a monitor playing the aforementioned video work (posters and stamps, 2018). (3) The video is a first-person recording of a computer screen on which an unseen operator peruses the poster and stamp listings on eBay. There’s an oddly doubled sense of voyeurism when viewing the video, a feeling that you’re surveilling the Internet proclivities of someone as they look through someone else’s unwanted things. Like the vinyl record in Erasmia Pulchella, posters and stamps are familiar collectibles that double as records, in this case of occurrence and transference. Apart from providing the viewer with a brief foray into the categorical offerings on eBay, the video lends context to Revington’s collages upstairs, revealing both the occurrence and transference of their disparate elements: found on Internet, purchased, shipped to collector. The two basement works form a narrative tableau through which the speculative daily operations of the collector can be imagined. Locate and purchase a new object for the collection on eBay, bike to the post office and obtain the shipped object, amalgamate the object into the collection, locate and purchase, bike, amalgamate, on and on. It seems appropriate that these works have been relegated to the basement, the most common domestic tier for storage, hobbies, and other DIY endeavours.

While a DIY aesthetic is evident in the scrappy resolve of Revington’s collages, there is another DIY notion suffused throughout the exhibition, that being the efforts of its actant collector. As a subset of DIY endeavours, collecting might not be the most immediate correlative. Nevertheless, it is an activity with a constructive outcome that, like most DIY inclinations, exists within a community of individuals sharing the same proclivities. Depending on the community, these individuals may periodically coalesce into a collective and then disperse to continue their individualized efforts in relative isolation. (4) Therefore, collecting can be both a highly private endeavour and one that is publicly engaged, with the potential for a single collector/collection to move between these two positions. Karma, on the other hand, is more difficult to contextualize as a DIY endeavour, particularly since the concept itself is multifarious, existing as a spiritual principle, a metaphysical position, an experiential paradigm, and an ethical model. A simplified definition of karma is one of cause and effect; what goes around comes around, situating karma in the daily entanglements of human-to-human interactions, which further distances it from solitary DIY imaginings. However, karma is often conceptualized as a type of accumulation in which one enacts good deeds to collect future happiness. Within this accumulatory karmic model, could an individual systematically collect karma as one would objects of a collection? Or would such an intentional accumulation negate its reciprocal potential?

The exhibition’s title, DIY Karma Kit, may indicate a predetermined set of material agents capable of allowing this intentional accumulation. Courtesy of its DIY modifier, the implication is that such a kit would grant its user the ability to collect karma solitarily, thereby circumventing the nebulous variables that may arise from human interactions currently folded into conceptualizations of karma. The result is an emergent methodology for collecting karma with and through things, an attempt to extract some latent karmic resonance from the jettisoned materiality of other people’s lives, maybe even your own. This is a micro-karma of material circulation apt for a world in which things vastly outnumber people and people are increasingly distanced from meaningful collective engagements. It’s unclear what sort of reciprocal boons this sort of karma might come to bear, although they too may be tethered to materials, like the continued expansion of the collection. The uncertainties regarding this kit and its speculative outcomes circle back to those felt when viewing Revington’s collages and their backwards facing frames. There’s an inversion at play, one capable of reframing how our relationships are mediated, enriched, and quite possibly compromised through materials.

And so the uncertainties compound and aggregate into their own collection, one that doesn’t necessarily resolve itself for the viewer, but then, that is typical of collections. They inch towards an indefinite state of completion, often settling on an abandoned finalization courtesy of collector disinterest or death. For many, the practice of art follows a similar trajectory; there’s a steady progression towards a distant point that once reached, only reveals a multitude of other points further in the distance. The collector, the artist, the artist as collector, they’ll continue on all the same, untroubled by indefinite objectives.

1. The following is the description for the YouTube video titled, September – Erasmia Pulcella 10”:

“September were a emo band from San Jose that existed from September ’94-May ’95. The band made 5 songs during their lifespan and played 2 shows. It wasn’t until ’96 that Tree records decided to put out the bands posthumous 10″ record. 4 songs made it into this album. The vocals were recorded out in the backyard. The other song made it into a compilation album.” https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qD8QeR6XFwU

Readers of a certain age and musical lineage will remember a time when rumours circulated regarding certain emo bands performing with their backs to the crowds because they were purportedly too shy to play otherwise. I have to admit, this was one of my first associations when seeing Revington’s collages, that the works were similarly shy, maybe even in a slightly coy manner.

2. Jean Baudrillard, The System of Objects, trans. James Benedict (London: Verso, 2000), 85-86.

3. For each exhibition Support produces a small publication titled MATERIALS, which is described simply as “a collection of references”. The edition produced for DIY Karma Kit features a sequence of divergent iPhone screenshots and photographs. One spread positions an eBay description of a poster next to a London bylaw notice for “grass/weeds exceeding 20cm (8 inches) in height”. On the last page there’s a text message from AR Adam, which itself is a lengthy quote from an unknown source (authored by David Rouse) describing the Schwinn Bicycle Company’s financial woes during the latter part of the 20th Century. Rouse asserts that Schwinn’s story is “an American story, now an all-too-common one,” wherein the once successful family-run company failed to keep up with market trends and went bankrupt. Comparing this reference to the bicycles (one of which is a Schwinn) in The beautiful man is a cow and the dirt-caked cars of Souvenirs, a relation to the post-industrial exigency in the Great Lakes region emerges. MATERIALS acts as Support’s didactic text surrogate, but unlike a didactic text it doesn’t risk constraining the viewer’s perception of the work. Instead, it allows for associative leaps to be made between the collected references and the work itself, integrating the publication more holistically into the exhibition as both a supporting document and a mobile work.

4. e.g., Members of a DIY music scene will likely coalesce more than members of a DIY pickling scene.

DIY Karma Kit was organized by Ruth Skinner and ran from October 20 – November 26, 2018 at Support in London, Ontario.

Feature Image: Garden Patch, 2018 by Adam Revington. All photos by Zoë Mpeletzikas.