Every Moment Is A Chance To Get Something That Lives On

29 October 2021

Vishal Jugdeo interviewed by Paul Kajander

Does Your House Have Lions (2021) is a 49 minute film by Delhi-based poet vqueeram and Los Angeles-based artist Vishal Jugdeo. Shot like cinéma-vérité, the piece moves around friends and lovers vqueeram lives with. It documents Delhi, Bombay and Goa, during the time-period of January 2016 to September 2020, and speaks to an intensified political atmosphere in India. This film is just one iteration of an ongoing collaborative process between vqueeram and Jugdeo.

For several months, I’ve had the pleasure of thinking with this complex and profoundly beautiful new work, which prompted much correspondence about Vishal & vqueeram’s working methodology and the many details surrounding the lived experience of producing such an encompassing project. Through his spirited responses, Vishal shared a wealth of contextual information that will offer an enriched experience of this vital document, which shines a brave and loving light on a house of luminous relations, burning brightly against the encroaching darkness of diminishing democratic freedoms in India.

Paul Kajander: Vish, I am so excited to ask you about Does Your House Have Lions (2021), your most recent in a string of collaborative works with vqueeram. You’d shared some early edits as you were putting it together, so it wasn’t until its public release through MOCA LA’s SCREEN series that I learned you’d given it this title. There’s so much to say about this work, but I want to start with what the title brings to mind: it comes from Sonia Sanchez’s quoting an anecdote about Rahsaan Roland Kirk who had told jazz producer Joel Dorn to buy a house that had concrete lions out front.1 By using this title, you and vqueeram are pointing to both Sanchez and Kirk and I couldn’t help but think about the latter’s ability to play multiple instruments at once. When Kirk played two saxophones and a clarinet simultaneously—it’s not just that you’re hearing these instruments together, like in an overdub—they sound different because they’re being played at the same time, with his crazy circular-breathing-stretching to activate each instrument. Knowing where this title comes from, I was thinking of your capacity as an artist to perform multiple roles simultaneously while making this work with your collaborators, and in this way, it feels like an echo of Kirk’s ability to push conventional limitations in straining towards a richer sound.

There are so many layers to consider in how the title Does Your House Have Lions rubs up against the content of the work itself. It’s quoting-a-quote that’s also a quotation, which opens an expansive line of thought about property, symbols, superstitions and narrative. It’s also funny and I love that Sanchez used it to introduce the reader to the profundity of familial love and loss that are the focus of her book.

When I first heard that you’d given the work this title, we were at a point in the pandemic where the city of Toronto was ending an eviction ban on the unhoused people who had set up encampments across the city. Attempts to invisibilize homelessness proliferate globally, and I can’t think of any city that isn’t suffering some form of housing crisis. Does Your House Have Lions also brings to mind the ways in which vqueeram’s shared home figures so prominently in the film. Do you think about the lions in the Kirk quote in relation to a kind of talismanic perimeter of love & protection you hope to draw around vqueeram’s house? Can you share how you came to this title?

Vishal Jugdeo: This is such a great question, and I appreciate it in all of its layers and stages. Does Your House Have Lions was vqueeram’s suggestion to me once we had finished the edit, which they pulled from Sanchez’s book of poetry. As soon as I heard it, I replied YES, without having much of a connection to the references beyond a faint familiarity. But once we looked deeper, it felt so appropriate. The quoting and re-quoting by a loosely linked group of artists from another generation felt totally right, as did Sanchez’s dedication “to all my sisters who have lost their brothers to AIDS.” I think we were both drawn to its symbolic and metaphoric possibilities, rather than the original anecdote being more literally about property acquisition. The lesson from Sanchez, who re-prints the quote from the liner notes of Roland Kirk’s Anthology as the first page of her book, seems to be about abolishing ideas related to property and ownership. It’s literally about chosen kinship, and as you say “a talismanic perimeter of love & protection.” I actually knew very little about Roland Kirk’s music until recently, but what you mention about his playing multiple instruments simultaneously is so beautiful, in particular the “crazy circular breathing stretching across,” which makes me think about these hard times, and how we learn to breathe with one another.

The film becomes a shelter of sorts, a place that holds intimacies and links stories together in the flow of everyday occurrences. In the panel discussion we held following the release of the film online, vqueeram, when asked about the camera as an invasive presence, replied something along the lines of “when you live with someone, you learn to accept everything they come with, so living with Vishal is getting used to having his camera around.” I was flattered when they said that, because I hadn’t thought of us as living together, even though the fantasy of cohabitation is something that I think we both think about (it’s what underscores our arguments about their unwillingness to get a passport!). Queer friendship is central to the project, and there is definitely a durational familial bond that I think we both feel, which has only strengthened with time.

vqueeram feels a strong affinity with the tradition of houses in the ballroom scene in New York, having been introduced to Paris is Burning (1990) when they were young. In many ways, vqueeram inhabits the role of a house mother, especially when they are around younger queers. And the house they live in is very much a place where people with nowhere else to live end up staying for a month or several. I remember vqueeram once described to me historical houses in India, passed from generation to generation, in which close-knit networks of trans folk live together with matriarchal figures at their centre. In contexts where it may be difficult to locate employment outside of sex work, and where people may be alienated from their blood family and therefore become housing insecure, these kinds of chosen-family bonds are crucial.

PK: This answer introduces the reader to so much. There’s such a bonded trust between you and vqueeram, and it speaks to your relationship that you entrusted them with titling and were rewarded with a choice that yields all these layers between what a house can mean and the specific textual histories and referents of that quote. vqueeram totally projects a house mother’s care and perspicacity: no nonsense, wise, fabulous.

VJ: Absolutely! I think fondly of a night after filming, when vqueeram cooked an incredible meal for the whole house and our little crew, and we all curled up to watch episodes of Pose projected onto the wall of their apartment in Delhi. I remember everyone’s glee and excitement as we recognized vqueeram in Mj Rodriguez’s character Blanca. Any cynicism I had around the mainstreaming of ballroom culture for a mass audience dissolved in that moment, as I observed how crucial these representations were for my queer Indian friends. They yearn to see reflections in popular culture that they can feel at home with.

PK: Going back to that moment from your MOCA talk, where vqueeram alluded to the presence of your camera…Can we talk more about that in relation to documentation, narrative and witnessing? It feels significant that when vqueeram refers to “your camera”, it doesn’t describe the position of you being behind the apparatus, aiming for objective observation. “Your camera” is more like a set of relations; you organize a crew of people for most sessions and are often filmed as an active participant as much as you are determining how to set up these shots. In a way, it feels as though you are inviting your collaborators to offer direction about how to best witness their experience. Can you share some reflections on your process of working with the DPs (director of photography), your decision to be in the frame, and this blurring between staged and witnessed scenarios? I’m conscious of the many roles you either enfold or challenge (less director, more organizer; less writer, more recorder) and I wonder what the feeling is in the room when you arrive to record?

VJ: The feeling is always a blend of relaxed and focused, plenty of teasing and joking around, but a lot of thoughtfulness and the result of us having spent days together before. You’re right that by referring to “your camera,” vqueeram is talking about the whole set of relations, but the DPs that we bring in are always somehow tangentially related socially, and the most recent two we worked with are actually close friends. We’ve learned to keep the crew super minimal. In two instances, our friend Amshu Chukki has traveled and stayed with us, so we are all I suppose “living together” for those days of shooting. It isn’t like a traditional shoot, it really flows out of our friendships and everyday cohabitation.

When I travel to India, we always give ourselves enough time so that we have a few weeks to just reanimate our intimacy, catch up, check in, see where things are at for vqueeram, because conditions are always changing. This project has always been collaborative first and foremost; we spend a lot of time talking about the film and what we think we’re doing with it, what’s working and what isn’t, before shooting more. vqueeram has always been adamant about not wanting the film to look “postcolonial” which I think refers to something that might feel more like a sincere, anthropologic documentary. As a result, the blurring between staged and witnessed that you mention is very much intentional. The film is constructed to give the subjects agency to modulate, as vqueeram notes in one scene, between transparency and opacity.

In terms of my presence in the film, at a certain point we decided that part of what we were doing was simply documenting the friendships and intimacies in vqueeram’s life. So because our friendship was deepening as we filmed, my entering the frame felt natural and necessary.

Over the course of shooting, we worked with four DPs, and all the subjects shot footage as well. It felt important that the perspective/lens kept shifting. I’ve never filmed something on so many devices and cameras, with so many operators; I wanted the gaze to feel collective. A part of trying different DPs was to modulate the energy in the room, figuring out what vibe would produce the most ease. Some of the more emotionally intense scenes are only possible because of a deep sense of trust and comfort in the room.

I love how you frame “inviting collaborators to offer direction about how to best witness their experience,” which was a huge part of the ethics in our filmmaking. Everyone has a say in how things are shot, and there has always been an agreement that if vqueeram or Dhiren wished to protect their privacy or dignity around anything, they are guaranteed final say in the edit. Because vqueeram is a co-author, we communicate about all the decisions that are made, both during production and post. vqueeram teases me constantly about being a “western academic who finds some tranny in Delhi, makes a film, gets tenure.” I love that they put that on the table, because then a part of the film’s work is to not be that, to try to undermine that dynamic at every turn, however possible.

PK: vqueeram teasing you that way is almost like saying, “we’re both bringing our contexts into this film, whether we want to or not”. I think that’s where the dimension of friendship & trust are most radical, that rather than holding your motivations or background in suspicion, there is an embracing of complexity that moves towards understanding/loving. Compared to your earlier work with vqueeram, what else has expanded in your thinking now that you’re also including other voices, especially Dhiren, who is such a major presence in the new work? And what language should we use to describe the additional subjectivities that figure prominently alongside vqueeram? Are they Contributors? Collaborators? Performers?

VJ: I consider Dhiren a collaborator certainly, because he was actively thinking through what kind of representation he wanted to bring to the film. How he presents his story is quite deliberate, even if his entry into the film was a bit happenstance. One day vqueeram and I had planned to shoot, but at the last minute they had to cancel to take care of some SOS work (they are always helping others in their community and household). We had a DP ready and equipment all set up, so vqueeram suggested that I experiment working with Dhiren. At that point, we had been filming more in the streets, in parks and on the subway, thinking through ideas about mobility and transit. So Dhiren and I took a long walk through Delhi at dusk, and he gave me a sort of sexual-geography tour, illuminating how men cruise and connect with each other, amidst the daily activity of the city. Dhiren’s research is very much around access, thinking specifically about how both caste and gender produce social barriers and necessitate transgressions. The next morning, we had planned to film at vqueeram’s apartment, and the pivotal scenes where Dhiren details experiences of rejection at the gay spa flowed out of the conversations we had the previous day. Just like that, he became a central character in the film! It’s important to note that how vqueeram and Dhiren decide to move the conversation in each scene is their way of writing the scene. In terms of the other figures you meet in the film, vqueeram refers to them as “the friends and lovers they live with.” Because they assume secondary roles, their intentionality isn’t necessarily as direct as vqueeram’s or Dhiren’s.

PK: How often do you review the day’s footage with collaborators? Is it more like they entrust you with the content and weigh in on edits only around those sensitivities to dignity, which you mention, and the potential consequences of being recorded speaking out in India?

VJ: We don’t normally review the footage as we’re shooting, and usually vqueeram really doesn’t want to see anything until it’s edited (and sometimes even resists watching then!) I check things as we go, but just for framing, exposure, sound, etc, in case there’s anything I need to communicate to the DP before the next day’s work. So yes, it’s usually not until there are substantive draft edits that I seek their input. Both vqueeram and Dhiren are intentionally measured in terms of what they choose to reveal, so it isn’t like there is ever much footage that they feel unsafe putting out. They’re cognizant of a surveilling gaze anytime the camera is on, largely because of their adjacency to activist communities, so very little that would put them at serious risk is ever recorded.

PK: Can you offer some insight around the total timespan that the new work is drawn from? Speaking of Dhiren, he undergoes a notable transformation that suggests at least a year has passed. It strikes me that the duration involved might present a lot of opportunity for reflection, improvisation and interruption to shape the overall film.

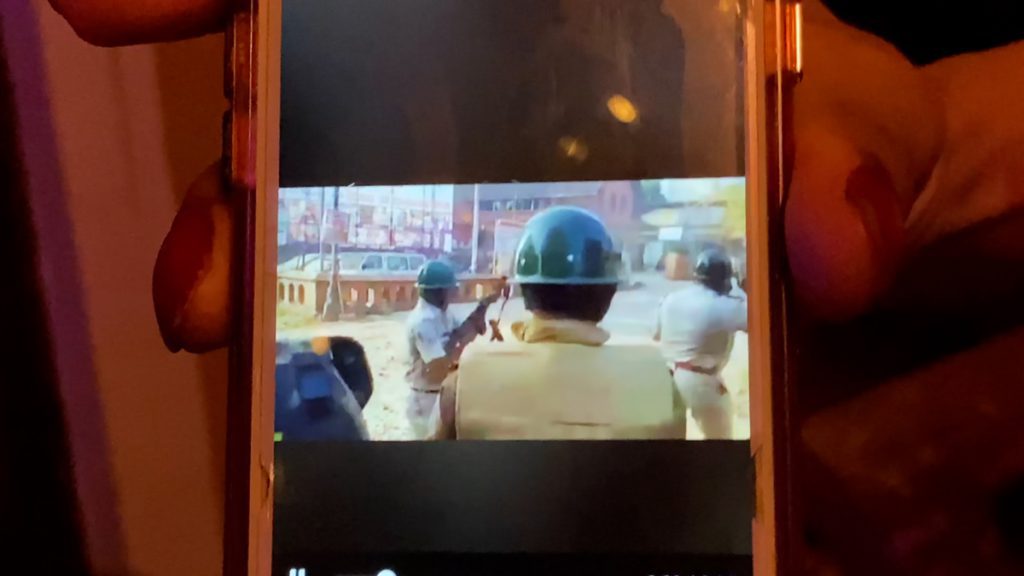

VJ: The opening scene of the film is January 2019 and most of the first half of the film was shot during that trip. That’s important because vqueeram refers to Narendra Modi’s impending second term (the election was May 2019). So for example, in the crucial scene on the roof, vqueeram wonders prophetically, “who amongst my friends will have to go underground when Modi returns to power in 2019?” There are a few scenes in that first half of the film that are from earlier shoots, most notably the scene where vqueeram’s housemate Natasha talks about the intensification of police brutality at a recent protest rally, which was filmed in January 2016. (Modi assumed office in May 2014).

The halfway point of the film is the most crucial jump in time from January 2019 to December 2019, which we indicate with the title card, “One Year Later.” That’s where you register Dhiren’s transformation from the shy, queer academic you meet in the first scenes of the film, to a more at ease version of himself, dancing in a pool to a disco song. The film’s co-editor, Nic Seago, suggested that we use Dhiren’s evolution as a way of charting the uncanny passage of time—he transforms drastically and so does the world around him.

In November 2019, India becomes a settler colonial state, and revokes the autonomy of Kashmir. Then in December 2019, the government introduces the Citizenship Amendment Act, a huge threat to the Muslim population. Massive demonstrations ensue across India, which you see in some of the footage we captured. It’s important to note that while all that was happening in the cities, we were witnessing it from afar, in Goa.

That scene in Goa, where vqueeram and Dhiren describe the wave of protests following the institutional murder of Rohith Vemula in 2016 is pivotal because they’re charting, in real time, a trajectory of the resistance movement that leads up to the massive demonstrations that we are following on social media and text threads. What you don’t hear in that conversation, is that their housemates Natasha and Devangana, back in Delhi, are participating in protests each night.

Five months later, in May 2020, Natasha and Devangana were arrested along with hundreds of other activists, journalists and public figures. They remained incarcerated for over a year and were only recently granted bail, which was challenged a day after their release. 2 It’s important to point out that all of the subjects in the film are aware of these impending, intensifying threats of state violence throughout each of our shoots, but I’m somewhat oblivious to the perilousness of their warnings. Back to my presence in the film—I see my role as a naive witness throughout, and while we were editing, it felt like my perspective was one of many entry-points for identification with the scenes: some viewers would experience the unfolding of events through my outsider gaze.

PK: This context will be hugely helpful for those who aren’t living as closely to the situation in India as you’ve been able to these past few years. It also answers my earlier question about how working with vqueeram has influenced your practice; the scope of your political concerns really expanded through this time and obviously part of that comes from the deeper knowing that emerges when living in a place and knowing people on-the-ground for a meaningful duration. I’m wondering if you can describe what initially motivated you to focus your attention on India?

VJ: This is certainly the first project I’ve made that speaks so directly to unfolding political events. It really wasn’t what we intended when we started working together, and vqueeram was very adamant about not wanting the work to become journalistic in any way. But when fascism forced itself further and further into their household, it became impossible not to address these realities in the film.

Thanks for asking about why I’ve chosen to work in India, because I think it does require some explanation. My ancestry is Indian, but my parents, and a few generations of my family since the early/mid 1800s are from Guyana; our ancestors were taken there as indentured servants. So, I’m of the Indian diaspora, but consider myself equally of the Caribbean diaspora. In 2010 I traveled to India for research, sort of on a whim. At the time I was working with performers in LA, making absurdist, experimental narrative videos. I was interested in seeing how my practice would shift working with performers in a different cultural context. The first film I made there was called Goods Carrier, and involved a group of theater actors in Mumbai. I was interested at that time in the history of what Shanay Jhaveri addresses in his book “Outsider Films on India.” It’s a region that a lot of people have projected fantasies onto cinematically. In a conversation with The Otolith Group about their film O Horizon (2018), I mention the necessity for our generation to theorize what the “diaspora gaze” may offer to the discourse, as I think it’s a unique way of looking.

With this project, I’m really interested in how important the queer familial bond is. When vqueeram and I met in 2015, it was through friends of friends, and the trust was already there because of that. Being queer and traveling to another place means that you can make friends quickly if you can locate the queers that live there. Several of my students (Kearra Gopee, V Haddad, Sam Richardson and Amina Cruz, for example) are working this way: collaborating with folks in other cities through a similar network of friends of friends of friends.

PK: Friendships & affinities are so significant across your whole practice and I’m reminded that your video works have often featured close friends or partners as performers. The way you describe working with vqueeram suggests that intuition & affection are crucial motivators in deciding who you want to film. Is it too much to say that your gaze still delights in how people are, rather than hiring actors to perform a certain stylized being? I recall an interview with Trinh T. Minh Ha about her early works and how she never had the budget to have actors rehearse long enough to yield convincingly naturalistic performances.

VJ: The times I have worked with actors that aren’t friends, I’ve only been able to get sort of surface performances, since I was also in the process of learning how to direct. I prefer working with people that I love because filming is a way of getting to know. I absolutely delight in seeing who the people I care about become for the camera, how they perform their authenticity in a way. There’s a kind of play that happens during a film shoot that can’t really be reproduced elsewhere in life. And there’s a certain life-or-death quality, because every moment is a chance to get something that lives on forever, so it brings everyone to their most brilliant selves, even when things feel awkward or not quite there. Getting that level of commitment to the project is what takes work, through building trust and friendships.

PK: Thinking about lives immortalized or commemorated, I believe it was shortly after you showed an earlier work made with vqueeram for 18th St Arts Center that Arundhati Roy published her novel, The Ministry of Utmost Happiness, which was met by mixed feelings, due, in part, to its romanticism around the portrayal of the trans woman protagonist. I have it in mind because Roy’s public persona and essays feel aligned politically with the progressive politics and humanitarian concerns you would share and because her work seeks to shine more light on the crises of human rights in India. I’m curious to know how her work is received by the community you work with, but also to contrast the populist style of her writing with the more complex formulation of your work, which as we’ve discussed, isn’t aiming to be a conventional “postcolonial” documentary.

VJ: So Arundhati Roy’s character in Ministry, Anujum, is actually based on Mona Ahmed, a legendary trans woman from Old Delhi who the photographer Dayanita Singh made portraits of for decades until Mona’s death in 2018. Mona is a very important figure for vqueeram, and the book of portraits of Mona that Singh made was a crucial early influence. In many ways, those pictures are probably why vqueeram agreed to work with me in the first place! I didn’t realize the extent of this influence until reading this essay 3 published last fall, in which vqueeram, asked by Frieze to speak about Dayanita’s photographs, emphasizes Mona’s legacy.

After becoming broadly renowned for The God of Small Things in 1997, Arundhati Roy’s primary contribution has been as an essayist, where she uses her platform to send warning signals to the West about the atrocities of casteism and of the rise of the Hindu right. While I respect her efforts, I think the critique from the community in Delhi that I’m friends with is the question of who that work speaks to and for. For example, her introduction to Ambedkhar’s Annihilation of Caste—which I admittedly found so illuminating—has been met with a lot of disapproval from the anti-caste and Dalit communities, who wonder why a person of such privilege would need to frame this important and radical text by a Dalit visionary. Does that framing not reproduce some of the casteist tropes that she aims to critique? And if the book with the introduction is priced prohibitively when the original text is free online, then there does seem to be an irreconcilable contradiction.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is Roy’s attempt to capture Mona’s greatness in words, and maybe it doesn’t totally work, but she did befriend and spend a lot of time with Mona, as I understand, and valued her as a subject, as did Dayanita Singh. vqueeram makes this point to me so clearly when we’ve talked about these cis artists’ work with Mona: let’s not undervalue the meaningfulness of the friendship and attention provided to Mona by people that have studied and documented her life, that too should be thought of as a form of love and care.

PK: Vish, you’ve been so generous and caring with your answers, I wonder if we can close now with one last question? Because you’ve worked together on a number of projects and nurtured this familial working relationship, do you have a sense of where things are headed in future works and will they include vqueeram? Behind this question, I find myself thinking of Steve McQueen, from his brilliant early film and video installations that were shown in the context of galleries and museums to how he has been directing narrative feature films and mini-series for the majority of the past decade. While the divisions feel much less clearly delineated today, do you see yourself continuing to pursue contemporary art contexts or are you and vqueeram interested in reaching a broader audience?

VJ: I’m committed to working with vqueeram to the extent that they will have me around. Even if we move towards collaborative projects that aren’t biographical, I will continue to document our friendship, because vqueeram is one of the most important people in my life.

While assembling the edit for the film, I was watching McQueen’s Small Axe (2020) series, which touched me so deeply. Hearing those specific Caribbean accents on a mainstream project is so momentous, as are the crucial, tragic and disturbing stories that he tells us.

I was also moved by what it meant to watch that work, not in a cinema, but in the privacy of the home. I designed this film to be watched in the same way, cast onto a TV, watched with relaxed attention. I’d love to work towards a broader audience, I really would, but I keep making these things that feel more like art, that have more idiosyncrasy and indeterminacy perhaps. But I do hope that the emotions in this work approach the scale of what I’d like to work towards. In terms of the question of audience, the moments when this film has screened online, many of the people in vqueeram’s community in India have been able to watch, and have been moved and excited by it, reposting stills and bits of dialogue on Instagram. I guess for me the audience that matters most for the work is the audience that the work is really made for: the community from which it emerges.

- Sonia Sanchez, Does your house have lions? (Boston: Beacon Press, 1997).

- https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/dec/18/india-clamps-down-against-citizenship-law-protests

- https://www.frieze.com/article/myself-mona-ahmed-revisiting-dayanita-singhs-landmark-photobook

Feature Image: Still from Does Your House Have Lions (2021). Courtesy of the artists and Commonwealth and Council.