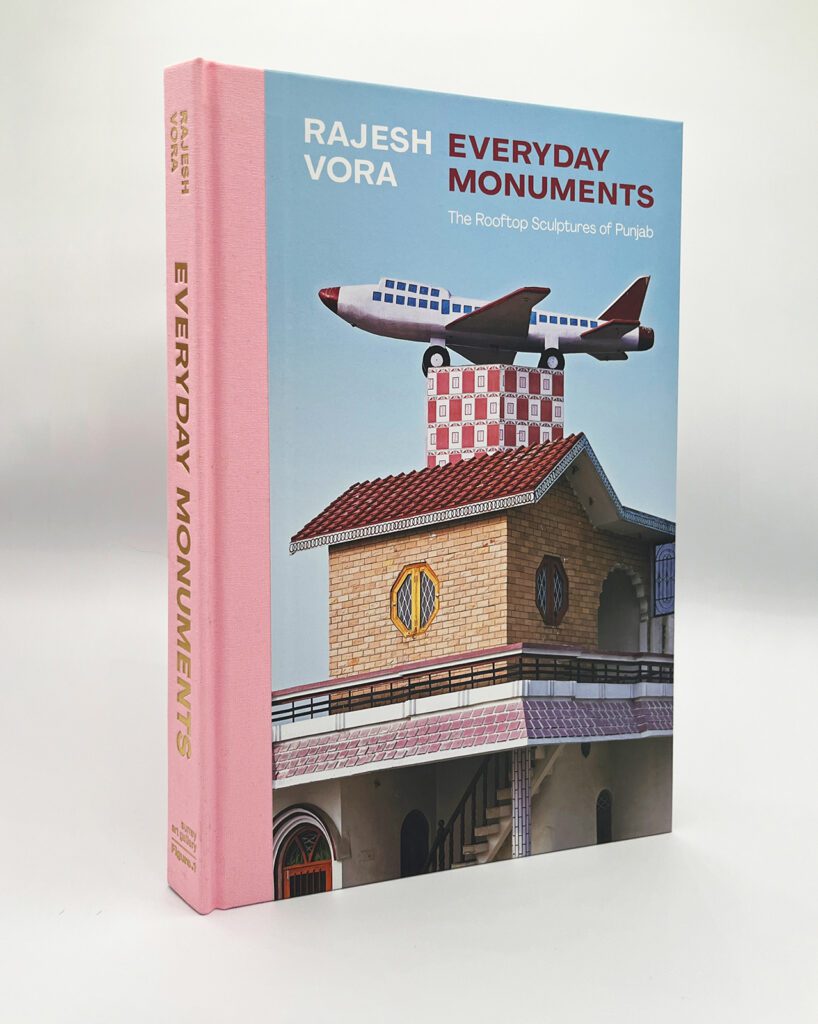

Everyday Monuments

1 March 2025By Prabhnoor Kaur

Rajesh Vora’s photobook, Everyday Monuments: The Rooftop Sculptures of Punjab is so large—or maybe my wrists are just weak—that I have to lay it on my lap to look at it. The act of reminiscing with a photo album was not a novel gesture for me: I remember being at my nani’s house in Ludhiana, Punjab, eagerly waiting outside the storage room. I would spend the entire trip waiting for the moment when she would pull out my mother’s and aunt’s wedding albums. We would sit side by side, the album like a blanket covering my legs and point to each person, asking “Who’s that? How come I have never met them?” My nani, of course, knew most of these people and would try to explain how they were related to us. We would rate the guests’ outfits, decide who was just there for the food, and judge their dance moves, now all frozen in the past.

I had never met most of these people but looking at these pictures so closely made me feel like I understood something about who they were in those moments. My favourite pages were always the gaudy collages of the bride and groom. In a time before Photoshop, the album makers would do their best. They would place a picture of the bride in the centre, surrounding her with four photos of the groom. The whole thing was then mounted on a gradient-coloured paper with a glitter glue border. By the time my youngest massi got married in 2005, this tradition had carried over to the new video format: a stock image of a flower would bloom to reveal the bride, zooming in to the soundtrack of the most romantic songs of the past five years. I am still enchanted with how over-the-top and delightfully tacky these albums were.

Looking at Vora’s photobook, I feel a similar captivation. Each photo features a brightly polychrome tankie: a sculptural water tank installed on the roof of a house, popular in the Doaba region of the state of Punjab. The houses themselves are a visual feast too, with their winding wrought iron staircases and glossy tilework. One particular photo makes me pause my flipping of the pages: it features a tankie in the shape of a bodybuilder installed on a yellow and maroon house in front of some mustard fields. If you stare at it long enough, you might see the fields roll in the wind. Looking at it now, so far removed from Punjab, makes my chest tighten. Poring over these pages, each tankie begins to look like a wedding guest in the photo albums: in the rippling muscles of the bodybuilder tankie, I see an uncle on the dance floor who stops every few songs to twirl and set his mustache; the gold plated kangaroo reminds me of those aunties who won’t stop comparing their children’s successes; and the spindly Eiffel Tower is like the guy with the “Guccy” belt. Perhaps this desire to showcase the prosperity found through migration is most clearly legible in the airplane tankiyan. Air India, American Airlines, and Air Canada are all represented on the roofs of Punjabi houses. Often these are the houses without laundry on clotheslines but with steel locks on the doors. By and large these rural mansions, and the tankiyan that crown them, belong to Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) who have immigrated abroad and are able to send remittances back to their families. When converted to rupees, these remittances make the family richer than they could have ever dreamed of being in agrarian Punjab.

Photographer and journalist Rajesh Vora had been on assignment for COLORS Magazine in 2013, examining this very desire to move abroad and documenting a ritual of offering model planes at the Talhan Sahib Gurudwara, when he first heard about the tankiyan. Curious to see for himself, he found that the sculptural water tanks were not limited to airplane forms but featured designs like bodybuilders, eagles, and revolutionaries. These monuments predominantly take on distinctly masculinized personas, underscoring the deep-rooted patriarchal structure of the state. Since the tankiyan act as stand-ins for the family and their status, they correspondingly function as emblems of the family patriarch himself.1 It marks the house and the wealth it represents as fruits of his successful immigration for all the community to see.

Between 2014 to 2019, Vora took six trips to Doaba and photographed hundreds of tankiyan across typologies. The phenomenon of making ornate tankiyan started somewhere in the 1970s, when the advent of modern plumbing made the water tanks a necessary part of every household. At the same time, people from the Doaba region began to move abroad to the US and Canada. As Vora notes in his conversation with curator Keith Wallace, these water tanks took a form similar to a matka, a clay pot used to keep water cool.2 According to the artist, one of the first sculptural water tanks was built by a contractor named Gyani Mahendra Singh Makh, who built “a reinforced concrete cement water tank that not only visually announces a sculpture of an army tank, but also has TANK spelled out across its side, prominently positioned on top of his four-storeyed house.”3 Inspired by Makh’s ostentatious display, other families began to follow suit, proverbially puffing their chests through the construction of their own tankiyan. Crowning the roofs of the homes, the tankiyan have become a source of familial pride, akin to a family crest.

While the stories we tell about diaspora have largely been unilateral—imagining a departure from a land where you are at home to becoming unmoored in the place you have migrated to—the tankiyan offer a counter narrative. For a place like Punjab, with a list of grievances against India ranging from the dividing and quartering of Partition, to the violence of today’s Hindu nationalist state, there is no sense of home. The condition of being Punjabi is characterized by a longing for another place, perhaps a pre-Partition whole. In this imagined Punjab, the average person can live unencumbered by the state violence, flourish in their farming, and imagine a future for generations to come.

Unable to go back, this desire must then be projected outward. Leaving the state seems like the only option and, as a part of a colonial empire, no place seems more desirable when it comes to securing a stable future than the West. It is the very introduction of this mythologized “better future” in the West that begins the diasporic process. When someone does immigrate, the illusion is quickly shattered. Life in a new country is hard. The money that seems so abundant is hard to come by and doesn’t buy you the life you had pictured. And it is lonely. Even more so because you don’t want to admit this to the people back home; that would be shameful. So instead you send money back and build a beautiful house. You tell your friends about the car you drive and don’t mention that you bought it second-hand. You wear new clothes and accent your speech and let them envy you.

Since the space where the labour is performed—the West—is obscured through distance from the place of consumption—Punjab—the fantasy of the West as a place of unlimited opportunity and prosperity remains intact. The hard work performed in rural Punjab could never bring in the income that working abroad could.4 Furthermore, as more people immigrate abroad, earn an income in dollars, and then buy “cheap” land in Punjab, the cost of that land increases exponentially. In the 2007 study titled “A Diasporic Indian Community: Reimagining Punjab,” historian Steve Taylor notes that areas with “a long history of migration to the West, the price of land is currently three times that of villages with little to no NRI [Non-Resident Indian] investments.”5 Coupled with the declining value of agriculture in the region, these inflated costs make it close to impossible for resident Punjabi’s to own land in their villages. In the fifteen-odd years since then, this situation has only been exacerbated. The tankiyan are erected as monuments attesting the success that immigration brings; it is these very tankiyan and mansions that inflate the cost of land beyond access to those without foreign sources of income. As the possibilities of a future at home dim, these tankiyan appear mirage-like: the promise of a better life, if only you can get there.

When I spoke to the artist as a part of my research, he told me that the process of creating this body of work was really a process of searching. There was no available directory of the tankiyan, which meant locating the houses all happened through word of mouth from local farmers and the remaining residents of the town. “It wasn’t easy,” he recounts, “sometimes you might find something but there’s no access to photograph it since I like to photograph them from the same perspective [each time]. So, I used to climb up on the opposite building, on the second floor, so it was more like a portrait.” In taking these portraits, Vora wanted to bestow a respect to his subjects. “Before I understood their purpose, these sculptures first brought to mind the different turbans that people in India would have adorned themselves with.”6 This standard portrait perspective lets you take in all the details of the tankie that would otherwise be obscured from the ground level, placing the viewer in conversation with the subjects. The winter fog diffuses the sunlight, casting everything in a dreamy haze. The house with the kangaroo tankie has left their Diwali lights up around his boxing gloves. You can see that under the Khanda, someone has added the Nike swoosh along with the brand name. There are flowers growing out of the headlights of the tankie that looks like a car.

In the summer of 2023, I was back in Punjab to do fieldwork for my Master’s thesis. I stood on the roof of a stranger’s house (I wanted to photograph a tankie on their neighbour’s house) and looked out onto the rural landscape. The fields were dotted with tankiyan. The sight was altogether quite melancholic: the more tankiyan a village has, the more people have immigrated. The tankiyan act as a map of absences, recording which villages inch towards becoming ghost-towns after their inhabitants have been seduced by the dream of immigrating abroad. These mansions loom large on the landscape, with forms imported from American architecture, broadcasting a kind of worldliness on the part of the owners. The mansion and the tankie act as proxy for the NRI, staking a claim to the homeland even in their physical absence, perhaps needing to ensure that the locals who remained in their village in Punjab knew that they had not immigrated for nothing.

Historian Steve Taylor confirms this: “NRI houses are an omnipresent symbol and reminder to the Indian residents of NRI distinctiveness and wealth.”7 It is because of the life they were able to build overseas, the wealth they were able to accrue, that they could have such a mansion in Punjab. The tankiyan sow seeds of desire in the hearts of those that have not immigrated; if they want a palatial home like this, they should look beyond the borders of this nation. It is in this way the desire to immigrate abroad reproduces itself ad nauseam. Each tankie in Everyday Monuments is a manifestation of a family’s singular identity and yet, as you flip through the book, the forms repeat: planes, eagles, bodybuilders, on different houses all across the state. Vora’s body of work highlights the very tension between the singularity of each tankie as an object and the collectivity of the tankiyan when read as a text. Maybe your fingers linger on the ubiquitous details painted onto the tankiyan or the signs of life on the roofs of the houses, but the afterimage remains the same.

It is this desperate desire for a better life somewhere else in Vora’s Everyday Monuments that looks so familiar. It’s a sense that permeates the air in Punjab. The summer I was conducting my field work looking at these tankiyan, I was staying at my nani’s house. The albums had been fawned over and put back in the almira. We were lounging on the bed, eating summer fruit off of steel plates as the TV played in the background. Some of the news headlines were as such: The weeks of torrential rains had caused farms to flood and destroyed this season’s harvest; Despite agreeing to scrap three anti-farmer bills, the Indian government still hadn’t taken any tangible action in that direction; A young Punjabi boy was murdered in central California… They interviewed people from the boy’s village, asking whether they would hesitate in sending their children abroad now. Of course we hesitate, they said, but we hesitate to keep them here too. At least abroad they have the chance to get a good job and make a good life; here, there is nothing to do but try to leave.

- While a good portion of the tankiyan take on these machismo forms, Rajesh Vora’s Everyday Monuments also features tankiyan depicting labouring farm women.

- Rajesh Vora and Keith Wallace, “The Rooftop Sculptures of Punjab,” in Everyday Monuments: Rooftop Sculptures of Punjab (Vancouver: Figure 1 Publishing, 2023), 146.

- Vora and Wallace, 146.

- Steve Taylor, Manjit Singh, and Deborah Booth, “A Diasporic Indian Community: Re-Imagining Punjab,” Sociological Bulletin 56, no. 2 (2007): 230.

- Ibid., 233.

- Vora and Wallace, 141.

- Taylor, Singh, and Booth, 230.

The publication, Everyday Monuments—The Rooftop Sculptures of Punjab (2023) is published by the Surrey Art Gallery and Figure 1 Publishers in Victoria, BC, and the exhibition Rajesh Vora: Everyday Monuments ran from April 9–May 29, 2022 at the Surrey Art Gallery in Surrey, BC.

Feature Image: Cover of Everyday Monuments–The Rooftop Sculptures of Punjab by Rajesh Vora. Published by the Surrey Art Gallery and Figure 1 Publishing, 2023. Photo courtesy of the Surrey Art Gallery.