History is a Passive Translator

2 August 2018

By Lauren Lavery

The history of a space is burdened. When looking at a space, these histories become apparent, but they also go into hiding. When I consider of the history of a building, I first think of the material it is made of: clay bricks, concrete, wood, plaster. But what about the non-visible elements, such as the individuals come and gone, the events hosted and the objects held within? The history of such abstract, in-between space is then what cannot be documented by the past alone, it must be translated into another form altogether, be it the written word, a photograph or a story. But these methods are often biased, and when it comes to art, not always as clear as they could be.

The space in question is Blinkers, a new experimental project space in Winnipeg run by four emerging artists, Kristina Banera, Hannah Doucet, John Patterson and Rachael Thorleifson. Located on the outer edge of the city’s Exchange District, historically known for its garment warehouses and artist studios, but more recently has been following seemingly inevitable gentrification patterns evident in many city centers; the space is built on a site of modern contention. However, the objects inside (and outside) endeavor to challenge the histories and implications of their current space with the inaugural exhibition, History Works Itself in All Directions. The group show featured the work of artists Ian August, Noor Bhangu, Alexis Dirks, Duncan Ferguson, Julian Hou and Luther Konadu. Even though the artists all work with material in distinct ways, their immediate differences were reconciled through the exhibition’s conceptual framework, focused on the flawed documentation process of spatial histories, material fragmentation and objects transcending ‘objectification’ over time.

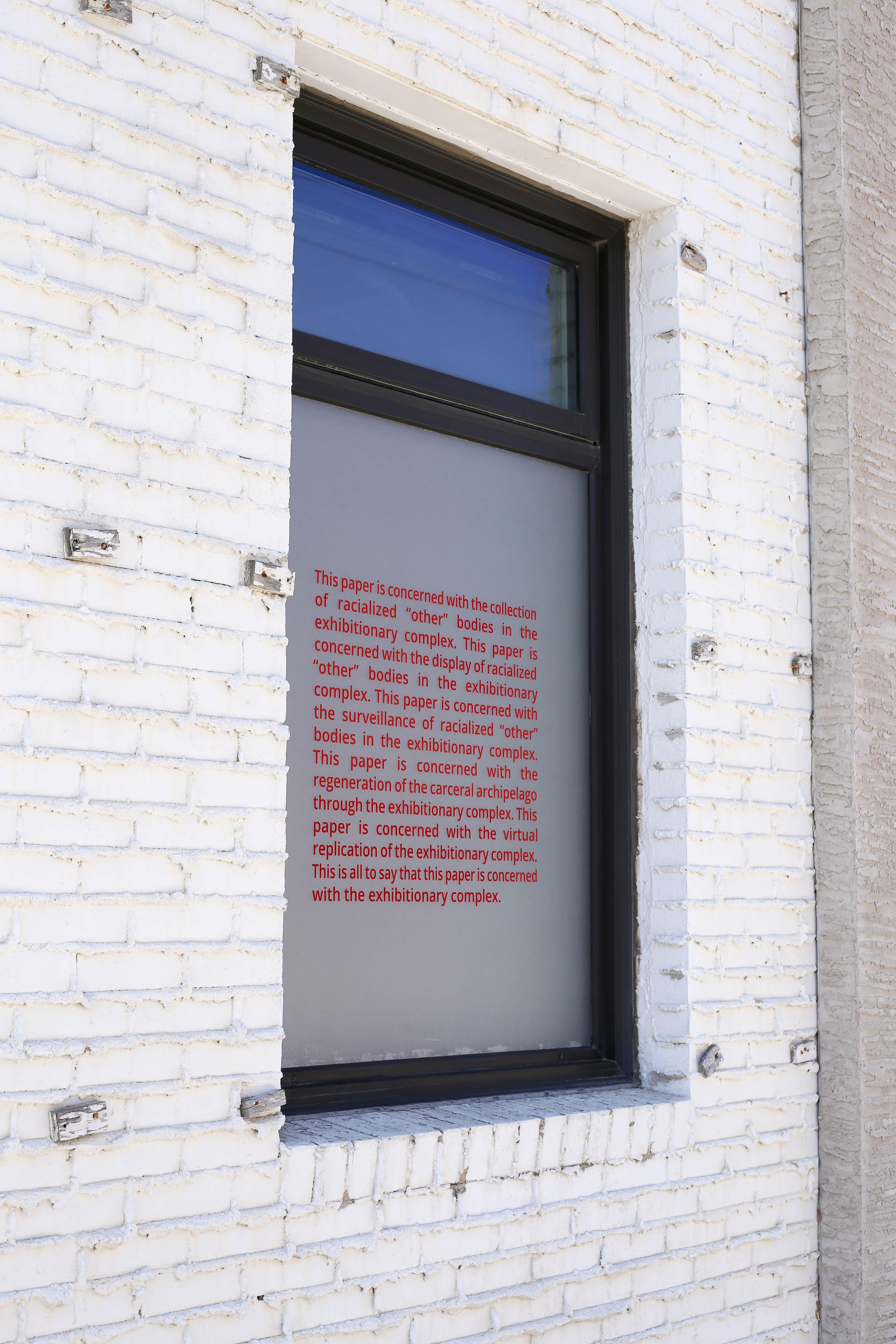

Before even entering the gallery space, the two front facing windows beckon to passers-by with two disjunctive works: the first window features a small plaster bust adorned with pastel pink and green buttons, perched on a slowly rotating stand. The second hosts a vinyl text offering a repeating statement: “This paper is concerned with the collection of racialized “other” bodies in the exhibitionary complex”. Against the white brick of the gallery’s exterior walls, the red font is a marked contrast that is more clever than it first appears. After reading the third sentence, I realize I’ve made a foolish error, the text is not the same statement repeated over again six times—a moment that had me re-evaluating the usual passivity to which I give the written word when it’s plastered on a wall—or in this case, a window. Noor Bhangu’s self-reflective contribution, Abstract: History Works Itself in All Directions (2018) plays with the powers of observation and reflexivity while hiding in plain sight. The full intricacy of this piece only emerges with the amount of time spent with it; its simplicity falsely empowers the viewer with the sense of its meaning at the quickest glance. Consequently, it was the different phrases which stood out the most—collection…display…surveillance…regeneration of the carceral archipelago…virtual replication—and also held back meaning. Her particular reference to the “carceral archipelago” from philosopher Michel Foucault’s book Discipline and Punishment (1975) as a relation to the racialized “other” bodies in an exhibitionary complex struck me profoundly. In this so-called body of text, located in the space and context of a gallery, the racialized “other” body becomes an object under constant surveillance—because it is different, it is other. The dystopian concept of surveilling and controlling the other is nothing new, as can be seen in every sci-fi alien film ever made, but the lack of integrity present in the artworld with galleries continuing to present works that objectify and sexualize the ethnic female body is disconcerting, not to mention the underrepresentation of female and artists of colour. The irony of Bhangu’s work is how it documents this history of art(ists) with words, illustrating just how easy it is to pass over the precarious nature of the racialized body within the legacy of the white cube. Even though Abstract… is able to revel in its own objectification, the artist’s references are also more attentively associated to that of the exhibition inside, a collection of works that together transcend the definition of their own objectivity.

Upon entering the gallery, the stunning nature of the floor reflects the objects that sit upon it, the first of which is a small kitchen still-life assemblage sitting about two feet high, consisting of a white plastic step stool, newspaper, a bbq lighter and a Brita water pitcher. After a more careful inspection, I notice an important alteration: a silver tube is rigged to one side of the pitcher. Brita Bong (How do I use this thing) (2016) by Duncan Ferguson gets straight to the point. I’m always surprised by the inventiveness that goes into DIY bong making, and Ferguson’s Brita version is no different. The modified purpose of the filter allows the more humorous tones present in the work to come forward, considering the filter would be purifying the bong water. All humour aside, the strongest aspect of the assemblage is each utilitarian object that makes up the work has an alternative purpose when put together—including the newspaper, displaying a page taken from the obituaries section. Obituaries are a curious thing themselves; brief histories of lives past, condensed into a few sentences highlighting those who surrounded them and what they achieved. How impermanent are the ways in which we remember these histories? Not just of people we know, but of the histories we voluntarily work to erase, like the water filter, each drop slowly subtracting the material and mineral histories out of the water before we take a drink.

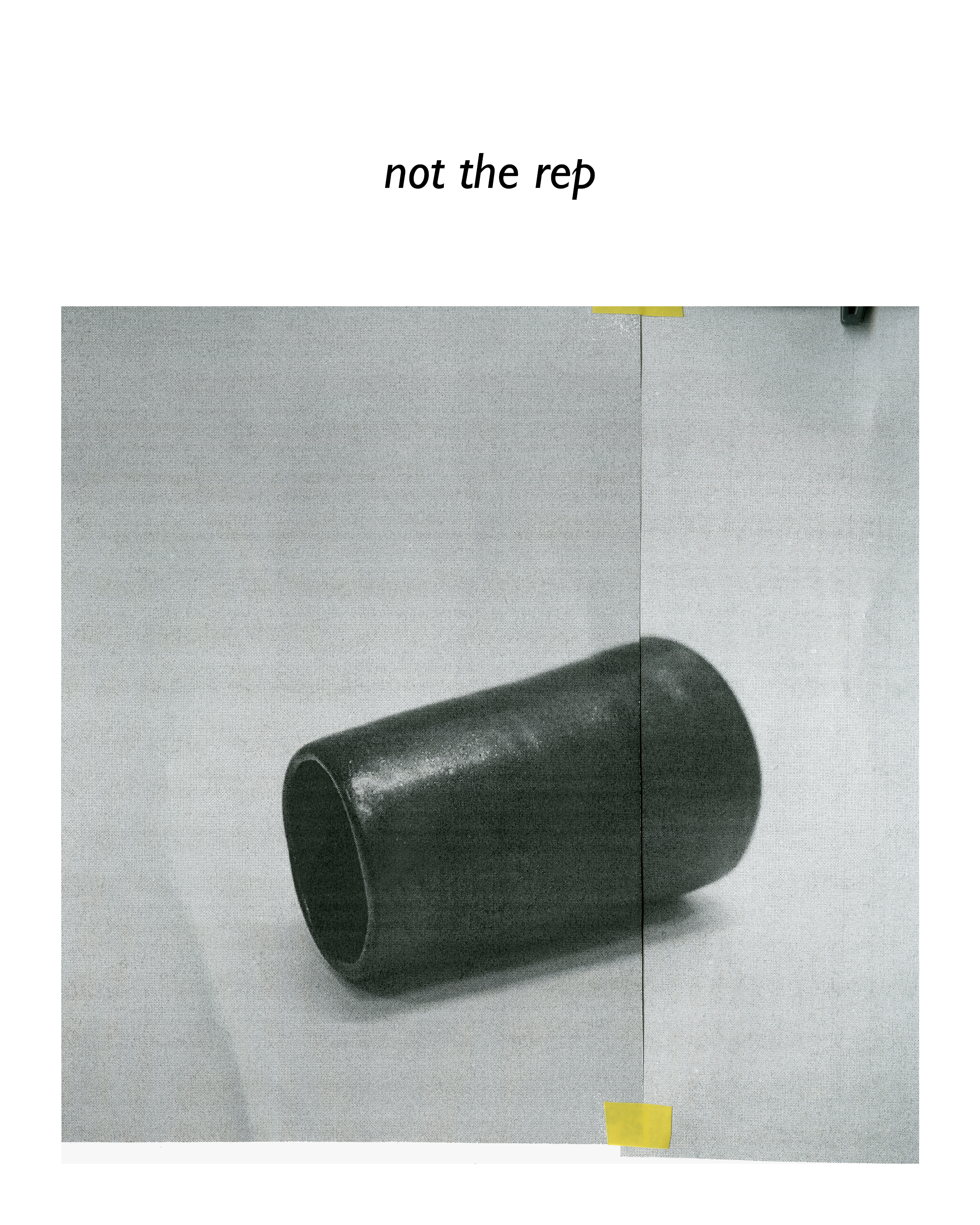

A small-scale black and white photo series is installed on the wall just left of Ferguson’s assemblage, called Untitled Portraits (2018) by Luther Konadu. The five subjects of the photographs are reminiscent of modernist sculptures, but if they were shot from some lofty aerial vantage point. The glossy black surfaces of the objects gleam dramatically in the light, accentuating their smooth, rounded edges, which recall the sculptural works of Henry Moore. But what exactly are they? Captions above the images seem to imply more questions than answers, stating: “not the performant”, “not the rep”, “not the shown”, “not the informant”, “not the case study”. The italicized font affiliates itself with the abstract images, but their pairing also doesn’t help to clarify the objects. Case study, informant, performant, the shown; all of these words are synonymous with helping to identify the subject, these five variations-of-an-object-subject. Then again there is a certainty, that while the viewer may not necessarily understand the relationship between the objects and the statements, the objects have nevertheless proclaimed what they are not. Perhaps the captions are right, since the objects inhabit certain in-betweens: they are not physical, the photos are not a true representation of their form, their current static nature is neither performing or informing the viewer about their true character. In a way, I found this conclusion extremely satisfying—identifying what the objects are is not as important as what they as subjects of the photograph are representing—the series instead seeks to challenge our expectations and interactions with the objects as portraits. Through using classical tropes of portraiture, Konadu begins to undo the narratives and associations that viewers employ when interpreting a photograph, thus also challenging how effective photography is in its ability to truly represent an object. This in mind, is photo documentation a flawed marker of history if we cannot understand the object in its original form? In relation to the exhibition’s greater thematic context, I would be inclined to think it is.

Tucked into the far corner of the gallery sits the installation titled North, South, Mine, Yours (2018) by Alexis Dirks. Four different sized plinths covered in a laminate marble design host smaller objects that look as if they’re three dimensional fragments cast off from the print on the wall just behind. Similar to Konadu’s photo series, the print by Dirks is an intricate maze of pattern, line and abstracted drawn images, but this time with the physical reference materials alongside. Deciphering the image proves to be more difficult than I first expected, since jarring lines cut through figurative forms, while perfectly reflected patterns suggest the use of a mirror to enhance the visual space. The simple checkered pattern catches my eye, and a feeling of deja-vu from just moments ago reminds me to look back at the sculptural elements. Atop the largest pillar sits a collection of items, one of which is a checkered fabric fragment directly pulled from the wall work. The piece is a digital print on silk and it sits adjacent to a dried leaf and two scraps of various material. As fragmented as the bits and pieces of this installation are, the austere formality and almost ruinous nature of each element establishes an appealing dystopian tableau. The pallid, bleached colour palette of the works—composed of materials that are also present in domestic living spaces, including marble, granite, silk, pegboard and stone—as well as their careful arrangement, implies something more intentional than this decaying quality first suggests. Assuming the various objects and ephemera in the installation all come from different sources—and therefore time periods—the piece can be read as a diorama of sorts, actors performing a silent, stationary play in which their material pasts can be inferred through their decontextualization in the white cube. Here again the viewer is presented with the exhibitions’ thematic eternal question: Is history—in all of its ardent attempts at documentation—a flawed way to remember, identify and interact with objects?

Ian August’s contributions are perhaps the most abstract in terms of their object-oriented presence. In the gallery’s second window (also seen from the first exterior window of the building) sits excavation number Kh, IV: 452 (plunderdupe) (2018). There is an immediate playfulness to the work, and upon each rotation the device squeaks and groans as if it takes considerable effort to move, enhancing the busts already personified charm. Curiously, this piece also has a twin, hanging across the gallery a large oil painting that depicts the face in realistic perspective. excavation number Kh, IV: 452 (frontview) (2018) duplicates the rotating piece the way in which only painting can, the colours are a shade or two off (although at this point who’s to say?) and certain features become more prominent after their translation onto canvas. For me the most uncanny features are the eyes—such attention to detail was put into capturing each small scratch and groove carved into the plastic gem-like shapes floating above the black void where the socket should be—a move which had me reevaluating what I saw the first time I examined the ‘real-life’ object. Assuming the sculptural work was produced first as a reference for the painting, the artist immediately incorporates the work into the canon of portraiture. However, it’s this uncertainty which makes these two pieces unique—depending on the order of which object came first, the question changes: what is lost or gained in the translation of one medium to the next? Considering my first assumption of the sculptural object being the referent for painting, both works should then be interpreted in the historic lineage of painting, as this order is (and has been) common practice. Yet, if the painting was made first, and only after recreated into the sculptural form, the historical precedent is lost, and with it the viewers ability to place the two works into a knowable context. Perhaps the only undeniable aspect of August’s two works is that each acts as the others’ sketch, and the ambiguous interplay between them will continue to eternally loop—as long as they both are present.

In the basement awaits the exhibition’s only audio work, titled Nexus Line (2017) by Vancouver-based artist Julian Hou. The soothing sounds of rippling water gently lap around the room, flowing in and out of a male and female voice speaking to one another. The audio echoes across the concrete walls, enhancing the ethereal and immersive quality of the work, while several distinct movements dissolve and evolve into new spaces, from a watery beachside conversation, to a walk through a lush forest, to an otherworldly piano melody peppered with a calming and ensuring voice speaking as if in a dream. In spite of the many separate directions the work takes the listener on, none of the transitions are jarring or unbelievable. The combination of sampled sounds, generated noises and melodies flow in the most atmospheric way, moving at a pace of how I imagine a tired commuter may come to endure their daily journey from work to home, collecting fragments of both the real and imagined world as they slip in and out of dream states. Listening to the soundscape in the chilled empty basement, it felt as if my body and thoughts were also separating at times, transporting me from sitting on a bench in the gallery to a familiar space that was always just out of reach. The sensation reminds me of the works upstairs, except instead of trying to differentiate the objects from the space in which they were situated, I was physically experiencing the obscure in-between.

Documentation can be a curious thing. It can take many forms, with the same object being continually interpreted and re-interpreted through the varying contexts until just a fragment of the original remains. The parts of the subject which are lost in this translation can be seen as flawed or inefficient, but they also open up more room for insights into an abstract in-between space. However unrelated the works in History Works Itself in All Directions seem at first, they are all innately connected through their ardent attempts to translate this indefinable space—not through what they say, but rather, through what they hold back.

History Works Itself in All Directions exhibited from April 27 – June 8, 2018 at Blinkers Art and Project Space in Winnipeg, MB, and was curated by the Blinkers organizers.

Feature image: North, South, Mine, Yours (2018) by Alexis Dirks. All photos courtesy of Blinkers.

*I would like to thank artist Luther Konadu and Hannah Doucet of Blinkers for their insightful input which helped bring this work into being.