Images of Mothers with Breasts: A Conversation between Amanda Boulos and Jasmine Reimer

13 March 2022

In She Can Cook a Potato in Her Hand and Make it Taste Like Chocolate, an artistic research and exhibition project led by Jasmine Reimer, she investigates Neolithic goddess mythology and symbols with twelve artists, researchers and academics, including Toronto-based artist Amanda Boulos. Interviews related to the project took place over Zoom and subsequent email correspondence due to strict COVID-19 lockdowns, when stories were told only through screens. In this conversation, Boulos and Reimer speak about their practices in relation to the visual language and body of “the Goddess.”

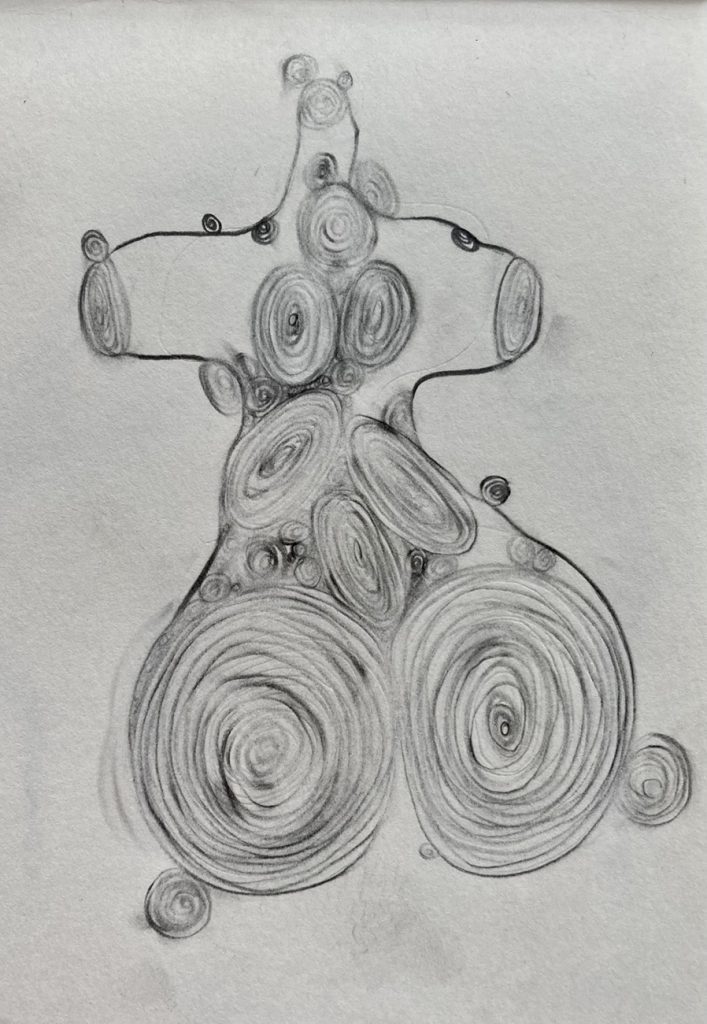

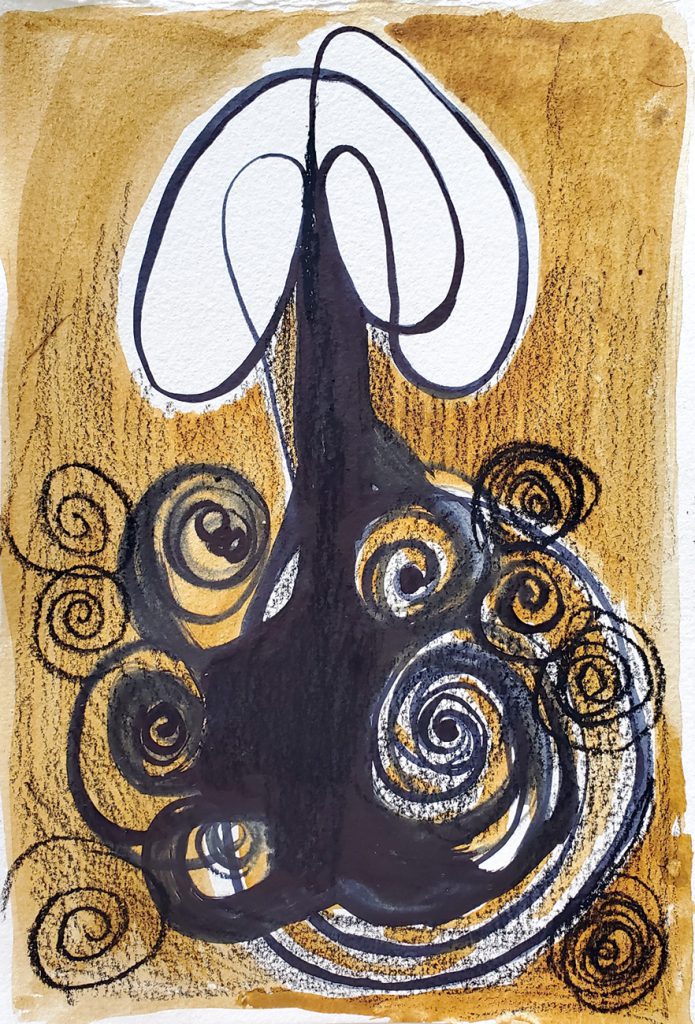

Boulos discusses her latest series, Mother’s Storage (2020), dedicated to her Mother as the storyteller of the family and to the nurturing nature of their relationship. She tells us how the abstract imagery emerges from familial narratives, body language and excessive smothering. She deeply admires and relates to Reimer’s goddess drawings from the recent series, The Great Round (2020-2021), asking about her inspirations for the towering charcoal works. Reimer’s The Great Round explores how “the Goddess” and her various manifestations as rocks, bodies of water, trees and plants helped Neolithic communities connect to non-anthropocentric lifecycles. In her drawings, Reimer adds to the mythology via gender-fluid hybrid forms.

Amanda Boulos: I’m very happy that you asked me to be part of your project, She Can Cook a Potato in Her Hand and Make it Taste Like Chocolate. It is nice to have the universal themes in my work framed in relationship to my identity, instead of my minority status as a Palestinian being centre stage. This is a method of curating that feels comfortable to me. How did you start conceiving of this project?

Jasmine Reimer: She Can Cook a Potato in Her Hand and Make it Taste Like Chocolate officially began towards the end of 2020 when I attended the Nida Art Colony residency program, in Nida, Lithuania. The project is based upon (Neolithic) goddess mythology and symbols, and influenced by the work of archaeologist, mythologist and linguist, Marija Gimbutas. Beginning in the 1960s, Gimbutas helped to unearth hundreds of goddess figurines throughout Europe as a lead archaeologist—uncommon in a male-dominated field. Through her rigorous research, Gimbutas found that regardless of their location, all of the goddess figurines, ceramic vessels and domestic objects had the same kinds of markings or styles of representation. For example, a wavy line, a checkerboard pattern, or spirals were found indicating certain Goddess animals or energy forms.

Some were hybrids with human female body parts, like legs and breasts, and other animal body parts such as wings and claws. Most commonly there was a human female-bird/snake goddess, and a human female-deer goddess. Many other animals appeared in these hybrids: frogs, fish, hedgehogs, birds of prey, pigs. Each one represented the goddess in her “epiphany,” the way that “the Goddess” appeared to human beings. She also manifested herself as certain types of rocks, bodies of water, trees, and plants.

I became very fascinated with the visual language of the Goddess because it was representative of a certain type of ideology, like a feminist ecology or non-anthropocentric world order. This was a very different ideology than what I, and perhaps many other people who grew up in Western culture, internalized in terms of their relationship to the natural landscape and the living beings within it. While in residence, I was awarded a grant to involve other people in my exploration, so I began seeking out artists who were also working with these subjects and ideas. I wanted to include different sets of knowledge and experience.

JR: Looking at your series of paintings, Mother’s Storage (2020), I wondered if there was a resonance with goddess mythology. What is your connection to the topic?

AB: I think about the Goddess and the visual language that surrounds her a lot, but they are always like little whispers in the back of my mind. Although I didn’t have goddesses in mind while making the work, when you approached me with your Google folder full of ideas, readings and images of goddess mythologies, I slowly began to realize that I was actually taking from that pictorial language. All of these materials on goddesses, and the visual language that comes out of those ancient ruins, are familiar and connected to the series. I thought about a mother’s body, how it manifests, and how it provides both nurture and nature. It shocked me that you saw all of that in my work, but it’s obviously there.

Mother’s Storage came from reflecting on my collection of past works about my mother’s recounted oral stories of living through the Lebanese civil war and moving to Canada. The series is dedicated to her as a storyteller, in part contemplating the tough, inherited family histories spanning the colonization of Palestine. The work also meditates on the hardships of being a woman and a mother during very volatile historical periods, and how immigrant mothers have to protect their children. There is an intense smothering that occurs; it comes from hardship, and the understanding that the world isn’t always a safe place.

Another element of this work is reflecting on how my mother speaks about her experiences and personal history. She shares stories by way of food and coffee—mothers sit you down, feed you, and talk. They don’t necessarily recount things as if they should be recorded, rather they tell stories that are fragmented; they share the good and the traumatic in a similar way.

JR: I’m curious about something you wrote on your website: “…the moment when one realizes they are no longer a virgin, that someone has passed, that they are unhappy, a complete disfiguration takes place; a force that shakes up your identity to form a new one.” I thought about the relationship to memory within that passage. Do you think there is a memory, or a remnant of something left behind after a major transformation?

AB: When the transformation happens there is something that becomes intangible. For better or worse, you have to leave your old shell behind in order to find a new one and grow with it. The memory shifts and changes and becomes a symbol, constantly mutating the further you get from that moment of transformation. With each mutation, the memory has more or less power over your present self. This comes to mind when working with my family’s stories, oral archives and my own memories.

JR: I’ve always been interested in the idea of cellular transmission, traumatic or otherwise. The body has its own kind of memory, a specific attachment to experiences that can’t be rationalized through thinking, but which deserve respect. There’s a certain knowledge in the body that is not accessible to us through rational means. Can you describe your process of working with trauma through family, friends and archives? How did this process come to be part of your practice?

AB: Much of my work on trauma is a reflection on how it changes a person, and how they might become someone or something new after a particularly intense event/encounter/instance. Upon realizing this I began searching for those moments of transformation in my personal history, my family history and significant historical moments. These moments are especially clear when looking through archives and listening to people’s personal stories about moving to a new place, having a baby, surviving war, or other significant life events. I knew through experience that working with these moments of transformation, or ruptures, were key to understanding how trauma is accumulated, encapsulated and overcome.

JR: Your mother and grandmother would share food and speak while eating; in a way, the food became a medium for transferring knowledge and feelings. Gimbutas said that as a little girl she would walk through her neighbourhood and as elderly women were outside working, they’d be singing folk songs. Gimbutas described these songs as paying reverence to the sun, the earth or to the Earth Mother. Rather than being taught the lyrics, Gimbutas learned the songs by hearing and experiencing them—a kind of absorption. Therefore, I believe she also absorbed some of the trauma they express. Looking at some of your paintings, I think of ‘absorption.’ Not like a sponge, rather like melding—a transference or becoming-with of sorts.

AB: Yes, the transmission comes through food but also through the body, via excessive hugs, abundant kisses and very subtle body gestures that are part of my everyday life. It is a ritual of smothering. The hugs and mouth kisses are so intense that they transmit all sorts of warnings and messages. I take these coded love languages and give them visual form. This is where the abstraction comes from: the morphing hearts, the mutant mother-daughter-animal, and the maze-like landscapes. For instance, Mother Carrying Daughter (Yellow Water) (2020) is a perfect example of this. The painting depicts two gazelles sitting in the baby gazelle’s piss. This image precisely describes my relationship with my mother, showing her tolerance of my body and her willingness to attach herself to it, good and bad.

JR: In mother-child relationships, I think there is a fluidity between the mother’s body and the child’s body. As this relationship changes, as people age and grow, I think it is important to remember that we were once literally connected, physically. For me, it’s important to remember that I was once inside the body of another person.

JR: When I looked at drawings of ancient kitchens, which according to Gimbutas would be filled with hundreds of copies of the same four-inch goddess statue, I saw it as a ritual offering based on a strong spiritual belief, as if to say, “I must put 500 miniature goddesses in the kitchen so that we can continue to eat.”

AB: It reminds me of a prayer; you put it out there and hope for the best. Similarly, there’s a shrine in a monastery in the mountains of Beirut, where women who are having trouble conceiving children can go and pray. They offer the shrine (housed in a dark cave) a big pot of food in exchange for a baby. Visiting the shrine and seeing hundreds of stainless steel pots was fascinating. I love how we can believe that bringing food to an empty cave, in a stainless steel pot, can manifest a child. We have such strong faith.

JR: Exactly, prayers in three-dimensional form. That’s exactly what goddess symbols and objects are: requests, communications, mediations.

AB: They are material forms, loved and cared for, evident in the time and effort spent constructing them. As artists, we understand the power and energy that goes into transmitting our thoughts, feelings, and wishes into a material object. This brings me to your sculpture and installation practice. Your works very much remind me of shrines. To me, there is a strong prayer or well-wish contained in each object and space you create. I’m thinking specifically about your owl sculptures and installations of all-green worlds. Are you transmitting a power of well wishes into the work?

JR: I started really focusing on these subjects in 2017 and was interested in the idea of talismans, or good luck charms, and the way that people imbue objects with significance. The Frog of Fortune series, made in 2018, is an example of this interest. With the series of owl sculptures, Me and My Earth Cult: Owl as Self-portrait, also from 2018, I began researching the symbolic meaning of owls in various cultures, and I learned about the owl as a symbol of death and transformation.

This symbolism gave me a way to connect with physical forms beyond materials, aesthetics, and our limited planes of experience. In hindsight I can see how I was able to connect to feelings, experiences, and sets of knowledge that I otherwise wouldn’t have. This led me to realize what myth can do for people, and in the process I recognized what an absence of myth I had in my life. I don’t know if I’m consciously putting a well-wish into the work, but I am absolutely hoping to imbue it with enough power that my work can do something for people.

AB: I’m curious about your minimal use of colour in Goddess Drawings (2020), versus Of, In or Under (2018). The green used in the latter is the same green that glows in the dark—it’s quite loud. I don’t know if I have mentioned this to you, but Of, In or Under reminds me of how humans can see more green values than any other colour due to our past relationship with forests. What is your relationship to colour and how do you use them in these two projects?

JR: I didn’t know about that, but I love it. I’m just starting out with drawing again after a long pause, and I’m bringing colour into the drawings very slowly, in stages, similar to what I did when I first started making sculpture. With Of, In or Under, the colour green was first a symbol for “nature” or “natural.” I wanted to question the validity of those words, but also use green in the way we tend to think of it as representing the outdoors. Nature is green; nature is trees, grass, mountains, etc. Green is not us, our bodies, our homes, our skin, nor the colour of animals. Colour for me is used to imply a significance similar to when someone highlights a text, or to evoke a feeling or sensation.

AB: Of, In or Under was wild in every sense. I get this feeling as though I’m in a forest dream where everything is radioactive, somewhere between life and death. The animals and inanimate doodads camouflage to survive this new green, human-made world. There is a sense that they are working together towards an unknown future.

JR: My intention was to remove boundaries. I wanted all of the work in the series to become one, or to appear as if in a constant state of change and transformation, which was a mysterious, energetic way to make work. I started to wonder what transformation looks like.

JR: I suspect that if I were to look into the darkest parts of your paintings, they would go on forever. You create amazing blues. Their saturation is so intense it gives me that sensation of looking into a void, as though it’s endless. Could you speak about that density?

AB: I construct those colours using many thin layers of pigment to create a gem-like appearance. They act like black pits and holes; these painted areas have a lot of power and calm to them, holding good and bad energy depending on the story being told.

In the goddess drawings it feels like I’m discovering a magical being while on a trail walk. They are completely surrounded by tall grasses but reveal themselves completely from where I’m standing. Perhaps I accidentally chanted something and summoned them, or I stepped in a magic puddle. Do you want to talk about the symmetry, framing, and posture of the goddesses in your recent drawings?

JR: I try to draw figures in poses that are simultaneously powerful and vulnerable. I want the beings I draw to confront but remain open. My main goal is to have them revel in their strength-of-body. Perhaps the beings in my work are a vision. Maybe all gods and goddesses are hallucinations or manifestations by those who need to see them and experience their energy at certain crucial moments in life.

AB: I’m drawn to how you create pits of darkness in your drawings, usually placed over figures in the areas where the genitals would be. They create calm moments in your drawings, as well as a sense of mystery, feeling as though they shift and change the longer you look at them. The viewer might know something is there, but they can’t quite see it. Can you talk about the dark “holes” in your drawings?

JR: When I apply the pastel or charcoal to the area where the genitals would be, that’s a very intentional way for me to speak about hybridity and gender and a way to break down language—no one can point and say that a figure is male or female. This is not because the genitals aren’t there, but they’re just blacked out. I’m trying to create a space or gap in orders of observation, language and identification for the same reason I would smother a sculpture in rubber: to dissolve its boundaries and give image and form to the word “fluid.” In terms of the traditional goddess figures, black indicated life, the cave or the moist earth from which all life springs. It wasn’t about death, it was about life.

AB: I can relate to that. Most of my paintings make use of darker colours and black because of their density, and what I think of as a capacity to hold energy. It’s not an emptiness that you can occupy easily, nor a white space that is vulnerable to smears from other colours. If you want to make a mark in darkness, it needs to be bold, because it is an already-occupied space.

Recently I’ve been adding dense, thick, black puffs of hair to otherwise very flat paintings. I’m trying to achieve what you do in your drawings, voluminous bodily forms. These black dense forms are relatable and comfortable, they are textures that you don’t tend to see in our slick, clean everyday world where we are bombarded with sharp, polished, white-leaning, backlit images, especially on social media.

JR: Why are you so interested in hair?

AB: I’ve always been attracted to hair and hairiness, it’s sexy, and I think about hair a lot. When I was in Banff in the summer of 2019, I made large drawings of hairy Sasquatches, which I loved. Additionally, I’m a hairy Arabic person. Growing up in the 90s, when body hair was taboo, it caused me to obsess even more. The big puffs of hair in my work are also inspired by my mother’s natural hair, which used to be very large, black, and curly, at a time before hair dying and straightening were commonplace.

JR: Some of the shapes you make are very similar to the archaeological burial mounds and sites I’ve been looking at: round, with an entry point. Can you speak to how your work addresses, explores, or reveals concepts related to death?

AB: Humans have a very specific visual language when thinking about death, which fascinates me: bones, nighttime, candles, burial grounds, flowers. I’m also very interested in how much Western society avoids thinking about death, creating an unquenchable thirst to engage with life, especially visually. I set out to think about death. The series In Memory of Mabid is dedicated to exploring darkness, stillness, and flatness in visual languages around death, while commemorating the death of a fictional character named Mabid, whose story takes place during the Lebanese Civil War. He was a civilian who died along the shore of the Mediterranean Sea.

AB: I’m curious about the natural spaces you create for your hybrid goddess figures. They remind me of the imaginary, fabricated landscapes I create in my paintings. Where do these figures live?

JR: I intuitively started drawing cattails, they symbolize the environment in which all these beings exist. The cattail came back instinctively from my childhood when I started drawing again. As a kid I would climb down into the ditches along the highway in Manitoba to pick them, then my mom and grandmother would coat them with hairspray so they wouldn’t go to seed. I love cattails because they are very strange, in the sense that they don’t fit in with other flowers and plants. Rather than a green leaf or a flower, you get a big, fuzzy, brown hot dog at the end of a rod. I love them. As it turns out, cattails are hermaphroditic. When I learned this, I thought, “this is perfect.” They’re also phallic, so I play around with that in the drawings.

AB: It’s funny you mention that, because I have a painting called Ontario Grass (2019) with an eerily similar backstory. My father is a car salesman, and as a kid I would ride around with him while he was working. I was obsessed with the obnoxiously tall and beautiful highway grass next to the road, which appears in a lot of my paintings now.

JR: It must be that our relationship and our memories are coming from childhood. The scale of everything we’re doing in our work is as if we have a child’s body: everything is taller and we’re looking upwards. That’s really curious.

Feature image: Mothers with Breasts by Amanda Boulos, courtesy of the artist.