Liza Eurich: pockets, postscripts, peonies

4 October 2022

By Kim Neudorf

Positioned like an offering at the entrance to artist Liza Eurich’s exhibition, a paper cone holds a gathering of peonies. However, on a closer look, the paper cone is a shirt sleeve with a buttoned-up cuff cast in pale-peach resin. There’s a muted, soft quality to the combination of violet-pink, dark green and pale pink colours in this bouquet. Combined with the cast sleeve, the impression is understated (perhaps this is a bouquet for a formal gathering) but with a dryly funny tone, as the sculpture performs its straightforward bouquet-ness with a knowing wink to the audience.

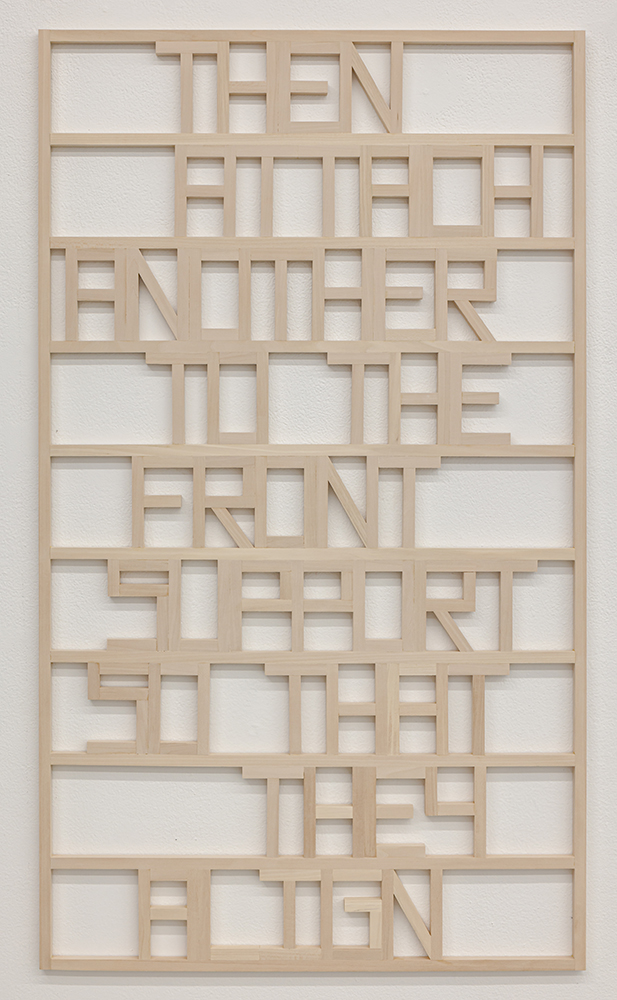

On the wall nearby, a text piece sits on delineated lines as in a notebook, the font filling each line to capacity in a tight frame, stating: “THEN ATTACH ANOTHER TO THE FRONT SUPPORT SO THAT THEY ALIGN.” Curiously, this simultaneously reads as a set of rules for construction (perhaps of the piece itself), a non-sequitur in the tone of a warning before entering the remaining installation, or possibly the artist’s own personal philosophy. Regardless of intention, the insinuated message seems to be that something further needs to be done to achieve alignment, but of what, it is not clear.

As I move through the main exhibition space, I notice a sheer blue material hanging like a hospital privacy curtain. Pockets embedded within the curtain are filled with dried leaves and analog film slides of dark, ambiguous images. The curtain’s title, viewfinder, no. 2 (2020-21) references a slide viewer, but instead of offering the device, the specimens are instead clouded by the deep blue and sheer-on-sheer moiré effect of the curtain. This leads me to question: What view is being offered here? Are we meant to see the images clearly to understand them?

In the far right corner of the gallery, a low tiered plinth is painted in a delicate pink. Upon this plinth are cast objects: a plastic bag, half a cabbage and a book, all pale pink in colour, as well as an unrecognizable object cast in bronze. This object resembles a ring for keys with odd attachments and raised patterns jutting out from its rim. The colours of these objects seem specifically, albeit mysteriously chosen by the artist, highlighting them as symbolic, yet what they symbolize is withheld. This lack of detail is further suggested in their straight-forward titles: a container (the bag), a form (the cabbage), a text (the book), and a comfort (the bronze object), (2020-21) all preceded by the phrase, she said it was things she loved. This phrase perhaps speaks to a level of removal from the original objects: while their cast quality suggests material remnants rather than direct copies, these objects may in fact link to something specific for the “she” who once loved them, but now that relationship is unfixed.

A text piece sitting directly across from the sheer-pocketed curtain reads: “THE EYES END UP NO MORE THAN TWO INCHES BELOW THE SURFACE.” Less process-driven, this text feels more literary, more romantic, yet is still spare of details. BELOW THE SURFACE is more unsettling than just above, suggesting eyes which appear both submerged and palpably present. To look no more than two inches below implies a shallow gaze—not too deep, but not purely on the surface either. I am thinking about the eyes below the surface. How did they “end up” in this position, and what do they see?

Back into the gallery, more objects are offered on pink plinths: the first (a scent) (2021), is a variation on the shirt sleeve bouquet. The sleeve becomes a vase for a stick of unlit incense in a bed of sand. Like the bouquet, this truncated sleeve enacts its role as vessel with a quiet dignity; its inflection, like that of the artist’s text instructions, is terse and straight-faced. The second object, (a comfort) (2021) is another bronze ring. Eventually, the phrase “teething ring” popped into my head which I later googled, finding images of the same telltale raised patterning. In a later conversation I had with Eurich, I was able to get confirmation on how these objects link to personal associations related to her experience of being a new parent (the bronze teething ring references a tradition of casting baby shoes in bronze, for instance), but initially, I was unable to make these connections.

Further on is a bench of the same pale wood as the text works, upon which sits a brush (a tool) (2021) with a wooden handle and coral-coloured bristles. The brush, appearing hand-made with long, soft pink hair, materially links to the surrounding objects (its handle, in pale unpainted and unembellished wood, is used throughout the installation, as are variations of the pink colour of its hair). Next to it is a stacked set of rectangular red cushions (a symbol) (2021), as if removed from a couch. The red of the cushions match the red of a cord tied to the brush’s handle, suggesting they are linked through colour. Partially visible between the cushions is a pale-pink object distinguishable as a baby’s bib, but it appears more akin to a flattened tongue, suggesting the presence of sensitive flesh between the protection of the cushions. I remember the text’s instruction to “end up” below the surface, and I make an association to how the bib, like the “eyes” of the text, appears in a similar position of looking out from the space it occupies.

The remaining text piece suggests a third way to read Eurich’s objects, stating: “PLACE THE TWO PIECES ON TOP OF EACH OTHER WRONG SIDES FACING.” Rather than think about what to place on top of what, I feel compelled to think about the possible meaning behind “wrong sides facing”, or the suggestion that I practice a way of facing wrongly. This is also a conversation between texts: achieving alignment, staying just two inches below the surface, and facing wrongly, are at odds in terms of orientation and instruction. This leads me to wonder if Eurich’s objects, seemingly placed in proximities meant to be decoded, might instead be phenomenological, or partially based on what each individual viewer brings through their perception of how the objects in each grouping perform together. Perhaps Eurich is saying something about how these instructions, messages or guiding philosophies exist simultaneously, requesting results or directing pathways that, through their coexistence, short-circuit a kind of certainty. These possible interpretations hang in the air, offering no clear pathways to follow, although perhaps in their tenuousness, deliberately invite multiple readings.

A postscript (or “P.S.”), as referenced in the installation’s title, arrives at the end of a letter, post-script. Remembered through the process of writing, the postscript also proposes a way of speaking, knowing and being that is always subject to new revisions. A refusal to completely reveal or define themselves, as many of Eurich’s objects do, is echoed in the way the materials shift from protective, private roles (partial objects cast; occluded evidence) to bodily softness, gentleness and fragility (a wall of sheer fabric; the touch of hair and skin). The works in the exhibition all present bodily gestures beyond resolution: the body as a container emptied out, a raw cabbage which resembles a brain, flattened cushions as a flattened body protecting vulnerable flesh and a brush which becomes less tool-like and gentler, perhaps turning towards the work of caring for the self and others. In pockets, postscripts, peonies, objects are simultaneously ethereal, while also sturdy supports and sites for orientation.

*** postscript ***

In further conversations, Eurich explained how the blue sheer curtain is based on the curtains of her home as “protective threshold[s]”1 between outdoor and indoor space. Within the context of the pandemic, these thresholds kept Eurich and her family safe. For Eurich, peonies are a reference to her grandmother’s garden, and they are also tied to the idea of a promise, such as that of a pre-COVID state, “Not a ‘get happy bouquet,’ these flowers can’t stand up to time, even while they hold present, past and before-times simultaneously. They are able to hold all these feelings, refusing to pretend that there is only one space—a return to a state of equilibrium, where I might feel I have more agency again.”2 Eurich described how peonies and bouquets are inextricably linked not only to a version of herself that no longer exists (including a relationship to her productivity in the studio), but that their specific temporal proximity to that self symbolizes a promise of what is no longer as accessible or possible. To go back, Eurich explained, would be like asking her to forget what she’d been through and to pretend that nothing, including her output in the studio, had changed.

In relation to the idea of a promise embedded in Eurich’s peonies, in scholar Sara Ahmed’s “Happy Objects,” the idea of a promise plays out when certain objects promise happiness only when other objects, orientations, and feelings are hidden or negated. As a general example of happy objects, Ahmed refers to how certain food as linked to happiness often depends upon certain conditions (mood, being in solitude or with others, appetite, memory, etc.) to produce that happiness. The contingent nature of happy objects, also linked to behavior and expectations from a family, social group, community, or career, can promise a shared happiness that is conditional. To Ahmed, “unhappy”3 objects can happen through a refusal to perform correctly for a group or community to gain acceptance, which can disturb or challenge that group or community. When a shared idea of happiness is based upon a culture of productivity within a career (such as being a professional artist), fulfilling that promise of happiness can require a constant, publicly performed productivity for continued (rather than secure) belonging, whether socially or through perceived marketability. To challenge this—by refusing the promise—is to promote unhappy objects.

In pockets, postscripts, peonies, Eurich attempts to thwart perceived expectations of what it means for materials, for symbols and for herself as an artist and mother to self-disclose without abandoning the modes and temporalities of working and living (“the messiness of the experiential”)4 which led her to the resulting artworks. In relation, unhappy objects hold onto baggage otherwise edited out when in service to the promise of normative, capitalist ideas of health and happiness. In this way, holding onto can be a holding back, a refusal of instruction in order to short-circuit the notion of an object being useful. For Eurich, reserving the personal can provoke “a slowing down of perception and seeing…foregrounding process over a linear goal-oriented trajectory. A space of potential, of transformation, of escape.”5

Eurich described her material decisions as emerging from “weird ways of trying to communicate”6 as an artist and mother during lockdown. Relating these modes of communication to decisions based more on intuition than conscious thought, Eurich sought forms as containers and supports such as the pocket/sleeve, bag/vase, and cast/carving to hold these feelings and articulations. The pathways of connection made possible by the objects are a result of a gut process of dismantling language, self, productivity, and shared orientation. This dismantling is experienced by Eurich as a “simultaneous”7 and continual transformation. Perhaps what is passed on between the artist, work and audience is not access to Eurich’s experience by way of a shared attunement, but the gesture of turning towards the how of the work’s arrival. It is through and in proximity to what Eurich calls the “lengthy and difficult process” of “the gut and the possibility of the P.S.”8 that her objects are able to speak, helping to mediate and integrate a personal experience of emotional, physical and creative transition.

- Interview with the artist, 2021.

- Ibid.

- Ahmed, Sara. “Happy Objects”, The Affect Theory Reader (Durham: Duke University Press), 48.

- Eurich.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

pockets, postscripts, peonies ran from July 10 – August 21, 2021 at MKG127 in Toronto, ON.

Feature Image: P.S. she said it was things she loved: a scent, 2021 by Liza Eurich. Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid courtesy of MKG127.