Nadia Gohar: Mudstone at ESP

20 December 2019

By Chris Andrews

The day before visiting Cairo-born artist Nadia Gohar’s Mudstone at Erin Stump Projects, I read in the news that Mohamed Morsi, the first democratically-elected president of Egypt, had died in court—or rather, was forced into living in prison conditions that may have led to his early passing. Morsi had eventually betrayed the same democracy that brought him into power, and with it, the hope that many had following the events of the Arab Spring. As if in response to this symbolic event, though only a timely coincidence, Gohar’s exhibition uses material as an embodiment of democracy. Through this keen interest in objecthood, an environment is created where every being, every thing, is granted a voice, and the importance of each material radiates. It is through this material vibrancy that Mudstone gestures toward the role of humble objects: the exhibition is a call for democratized symbols, vernacular value.

Made of composite-wood, a platform spans the width of the gallery and is raised just a few inches above the gallery floor. The pit becomes a framing device for three homogenous sculptural works, Observations I – III (2019), placed in its centre—from which all other works seem to stem. Gohar employs the visual language of archaeology with this constructed “pit” in the gallery’s centre, akin to those used to excavate remains and objects in Ancient Egypt. The construction of this framework invites the question of how value is attributed to objects unearthed through archeological practices. What is kept, and what is left to erode and decay into dust?

Observations I – III are “recreations” of objects and scenes that might be found in such an archeological dig: objects of the home, garments, detritus, material fragments, vessels. Of these works, Observation III stood out as the exhibition’s punctum, inviting tension into an otherwise composed scene; ruched white polyester fabric is stretched taut, as if strained, between two sides of a flat frame. The frame is concrete pigmented a saturated-terracotta colour, cosplaying as clay. Small flower petals made of concrete lie on the sculpture’s ruched fabric on either side of a yellowing plant stem, appearing together like a discarded pressed flower. The use of concrete is considered: its mimetic relation to clay subverts the material’s typical use. Concrete is used as a “border” to frame the objects it typically covers up, the way concrete buildings sit atop ancient cities like Cairo. These materials within the frames touch, overlap, and entangle, and the relationships that emerge from their convergence show a soft negotiation between each fragment and their place in the carefully-arranged whole.

This “soft negotiation”, as characterized here in the subtle and intricate nuances of Gohar’s sculptures, promptly becomes the antithesis of the monumental modernist sculpture: if modernist sculpture attempted to touch the sky in its verticality, the works here defiantly splay themselves across the floor in clear objection. Their newly defined un-monumentality, in material and aesthetic, disintegrates or otherwise entirely disinterests with the ideals of didactic, often male-dominated, sculpture.

The sole of a shoe, fabric from a yet-constructed garment—the materials in the pit exemplify Gohar’s practice of collecting un-precious objects and thoughtfully assembling them into provoking arrangements. The power of these sculptures lie in their congregation—or more appropriately, their democratic nature. As there seems to be no set rules for an object’s exclusion, we see Gohar as a conduit for the radical acceptance of all materials into her arrangements, creating a preciousness that comes from their being together, their sociality, regardless of each object’s individual value. This practice follows a lineage (and an often-overlooked art historical canon) of assemblage artists, as writer Mitch Speed recently recounted in Momus, “Artists like Robert Rauschenberg and myriad ‘Outsider’ art assemblagists—often artists of color, ignored by official art history—incorporated the neglected objects of life into seemingly chaotic sculptures that possessed subtle rhythms of accumulation and omission.” (1) It is through this poetic act of assemblage that Gohar creates a democratic body in the objects’ equalized position. She negotiates the value of discarded materials, imbues them with a sense of importance. In so doing, she harnesses a sense of order amongst fragments and remains.

Near the back of the light-filled room, Mobile II (2019), hangs from the ceiling with fabric draping down from its center. Its bricolage structure is composed of clothing hangers and the metal tubes of garment racks, a corollary to the artist’s involvement in the fashion industry, one of many subtle references that contribute to a collective picture of the artist’s own identity throughout Mudstone. The fabric is hung from the ghostlike construction by no more than the pinches of small yellow clamps, shaped like peanut shells. As the fabric nears the floor, two clay rings clasp the fabric, gathering it into concentrated points. In this, and similarly in the other sculptures included in the exhibition, the artist evokes the concept of material memory. From the concrete’s origin as part of a larger stone conglomerate, to the hands that wove the fabric which drapes towards the floor, material memory is brought to the fore. Observed here as a (rather anthropomorphic) concept that an object (the falling fabric, for example) can preserve history, both of its use and how it was made, but also the culture from which it came. Objects in this vein can be considered vessels for historical preservation, each carrying a narrative with it, or perhaps memories are embedded into the object itself, inseparable from its very materiality.

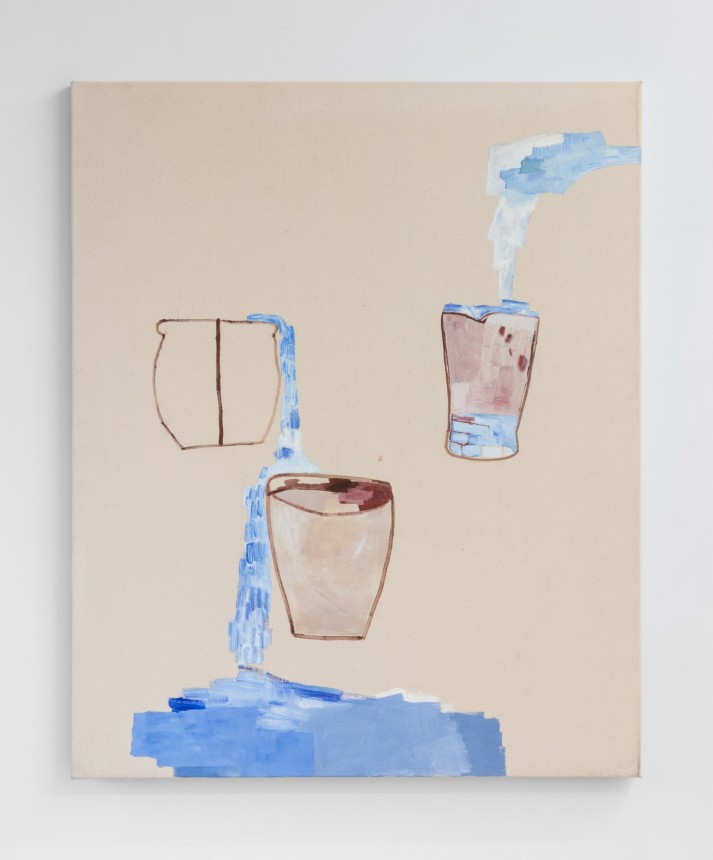

Gohar also employs a consistent material vocabulary on the walls—this time in the form of paintings of cerulean blue water on raw canvas. Three mid-sized canvases hang on parallel gallery walls as if radiating from the sculptures in the room’s center. Loosely rendered vessels are depicted in two of the paintings, minimally marked with baby-blue and terracotta, which cup, spill or overflow the water each attempts to hold. It is in this bare, vulnerable presentation that the artist leaves room for the contemplation of how objects were similarly displaced like the water, or left to the mud of the pit, in the processes of archaeological excavation that Gohar calls into view. And, as a result of this, how histories were created through these choices.

In its different parts, each with their own agency, the objects that make up the exhibition comprise a democratic whole; all contributing to a model of living together, here in this equalized space. There is a certain grace in the thoughtful arrangements, a quiet anecdote for democracy. Mudstone shows us how to remain centered in a time of destabilization, bringing us into its world of material and soft negotiation.

1. Speed, Mitch. “Wire and String: Olga Balema’s Sinewy Abjection.” Momus, 26 July 2019. momus.ca/wire-and-string-olga-balemas-sinewy-abjection/.

Mudstone ran from June 7 – July 6, 2019 at Erin Stump Projects in Toronto, ON.

Feature image: Detail of Observation III, 2019 by Nadia Gohar. Photo courtesy of Erin Stump Projects.