Ninga Mìnèh: Caroline Monnet at Montreal Museum of Fine Arts

5 November 2021

By Didier Morelli

In her first solo museum exhibition in Canada, presented by the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts (MMFA), Caroline Monnet chose eighteen recent works for Ninga Mìnèh, many of which had never previously been shown. Following her rise to prominence in the local (2020 Pierre-Ayot Award), national (2020 Sobey Art Award), and international (2019 Whitney Art Biennial) art scenes, the interdisciplinary artist of Algonquin and French ancestry made her much anticipated full-scale entry into one of Montreal’s most heralded cultural institutions. Ninga Mìnèh focuses on the architecture of Indigenous communities in Canada, specifically the cheaply and hastily built reservation housing that further entrenches First Nations peoples into economic and social precarity.1 Conceptually striking and spatially inviting, the exhibition draws on postmodern codes and mediums with a politically and socially incisive subtext, thus interpreting new conceptual horizons for the artist’s practice.

Ninga Mìnèh (“the promise,” in Anishinaabemowin) revolves around a two-part installation Monnet created in collaboration with designer Joseph Kalturnyk and architectural consultant Frédéric Caplette. Des fissures jaillit la lumière (2021) transforms a typical construction material into a full-scale pavilion; here we recognize the artist’s patented use of polystyrene, insulation, and gypsum boards altered by digitally printed graphics perforating their surface. Standing freely and casting shadows on the gallery floor, the walls of the room-like piece are perforated, allowing viewers to see through and across the room. The second part of the installation, Pikogan (abri) (2021), is a dome-shaped structure assembled from polyethylene tubes, PVC pipes, copper, Velcro, and steel. Invited to stand under the piece, the audience is positioned within the network of tubing, which gestures at the lack of potable water on reservations—one of many infrastructural markers of neo-colonial practices that continue to disenfranchise Indigenous communities by threatening their health, safety, wellbeing, and sovereignty. It is in this way that Ninga Mìnèh infiltrates the Canadian colonial landscape and unsettles its architectural codes and hierarchies, a motif Monnet also investigates in previous filmic works that prod at the infrastructures of her native Gatineau-Ottawa region (Gephyrophobia, 2012), as well as Northern Quebec and Labrador (Tshiuetin, 2016). Des fissures jaillit la lumière and Pikogan (abri) activate these previous architectural explorations into three-dimensional form, endorsing change through poetic imagination and responding to the current built environment imposed by the 1876 Indian Act.

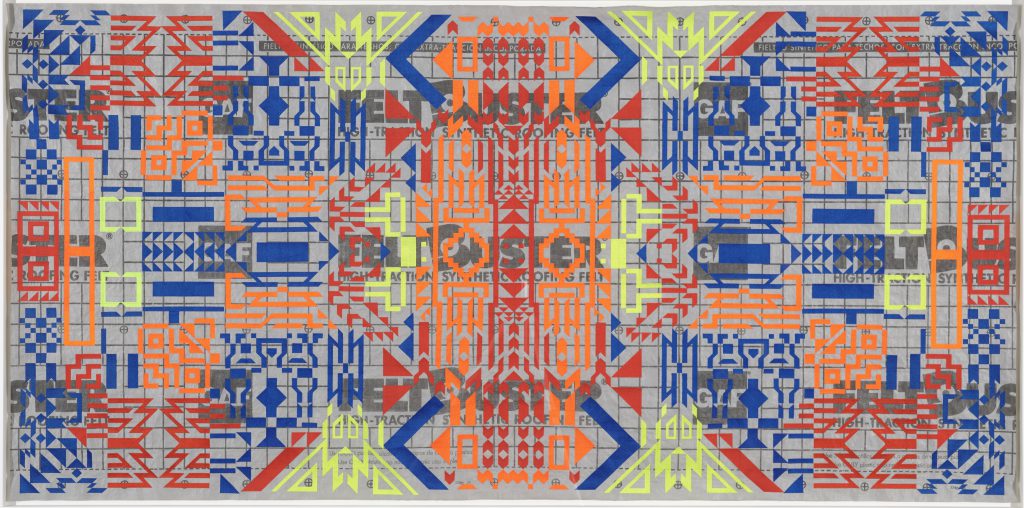

Throughout the exhibition, Monnet elevates Tyvek, pink mineral wool, waterproof tarpaulin, air barrier membrane, synthetic roofing felt, insulating sheathing foam, and pressed wood into objects of contemplation, with a critical eye to their material importance in the construction of contemporary Indigenous life. These units of construction have come to define the ghettoization of reservations by federal and provincial governments, large manufacturers, and other extractive industries. Functioning as readymades, these incorporated, branded, and easily recognizable construction materials are now laid bare. The only two photographic works in the exhibition, Chambre rose 01 and Chambre rose 02 (both 2021), suggest how these materials tend to creep up and become present in homes that have not been properly built or maintained by those with the power and wealth to do so. The serenity and beauty of these two images betrays the nature of pink mineral wool, which is both toxic when left unprotected and subject to rot when exposed to the elements. The photographs echo a piece on the same wall, AKI (terre) (2021), a bold plexiglass encasing of pink mineral wool that spells out “aki,” the Anishinaabemowin word for earth. With this juxtaposition the viewer is reminded that this legacy of unfinished, unsupported, poorly funded, and dehumanizing construction is at odds with the land itself, and the Indigenous peoples and communities it purports to enfranchise.

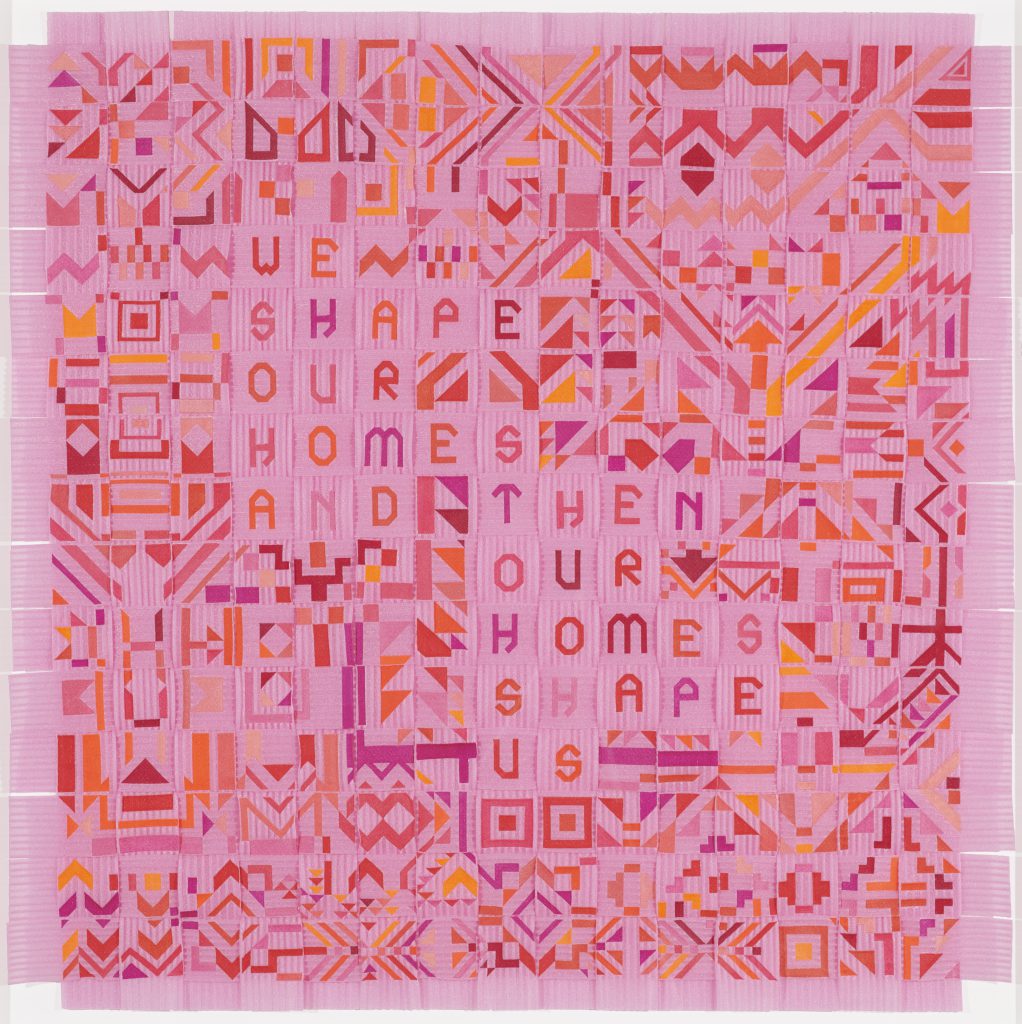

We Shape Our Homes and Then Our Homes Shape Us (2021), an embroidery on sill gasket that bears its title as an inscription in bright pink and orange hued patterns, deliberately accounts for how architecture is embodied by those who inhabit it. L’avenir oublier (2021) and L’union fait la force (2020) use air barrier membranes floating off of a backboard to create the effect of motion as the viewer passes by. Meant to evoke the fluttering feathers of a black crow, or the cartography of a village viewed from high above, they reimagine the kinetic nature of the built environment and activate the exhibition space.

Towards the end of the exhibition, on the acknowledgements wall, the audience is informed that the exhibition’s main sponsor is Hydro-Québec. As I have previously written,2 the Québec public utility company takes cover behind “art-washing,” even as it struggles to negotiate fair compensations with Indigenous communities in the North.3 Due to Hydro-Québec’s prominent role as a leading patron of arts and culture in the province, it comes as no surprise that Monnet and many other politically engaged local artists have been beneficiaries of the company in direct or indirect forms. Contributing to the degradation of the land, sowing division between First Nations, poisoning and diverting large bodies of waters on ancestral lands, and bolstering the myth of “clean energy,” their sponsorship of an exhibition that specifically decries poor living conditions is contradictory to say the least.4 Just as the MMFA seeks to signal its long-term commitment to advancing diversification in its programming and collecting practices, Monnet’s exhibition provides ideal cover from the unsavoury alliances the museum continues to maintain.

Nonetheless, Monnet’s work continues to defy the status quo, asking uncomfortable questions of both the viewer and the museum with powerful narrative through lines, a promising acumen for the construction of spaces, and careful, skillful craft. From a distance, Monnet’s digitally etched, engraved, or embroidered objects are inviting, providing an accessible vocabulary of geometric shapes and symmetrical sequences. From up close, these colorful surfaces present layer upon layer of codified meaning. Located on a spectrum between microchip rhizomes and traditional beadwork patterns from Anishinaabe birch bark baskets, the artist generates connections between the intermedia messaging, storytelling, and information-sharing structures that shape our world. Despite the exhibition’s disarming beauty, Monnet’s work maintains the edges of conflict that they portend to highlight. At Ninga Mìnèh’s core is an ugly truth, denouncing colonial doctrines that continue to transpire in Canadian and Québécois society, culture, and architecture to this day. Bearing witness to the poor housing conditions and the lack of basic amenities like water, electricity, sewage, and Internet in many Indigenous communities, Monnet skillfully deconstructs to reconstruct the codes of reservation architecture to imagine them anew in confronting and probing ways.

- https://policyoptions.irpp.org/magazines/april-2021/the-blueprint-for-systemic-racism-in-first-nations-housing/

- https://espaceartactuel.com/en/128-spring-summer-2021/

- https://www.lapresse.ca/debats/opinions/2020-12-18/hydro-quebec-doit-arreter-d-ignorer-les-droits-des-premieres-nations.php

- https://bangordailynews.com/2021/02/07/opinion/contributors/hydro-quebec-has-left-quebecs-first-nations-behind/

Ninga Mìnèh by Caroline Monnet ran from April 21 – August 1, 2021, at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts, QC.

Feature Image: Memories Unravelled, 2021, by Caroline Monnet. Photo by Jean-François Brière. Courtesy of Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.