Portrait of the Artist as a Spiritual Seeker: Debi’s (Teenage) Theosophical Enlightenment at Afternoon Projects

1 August 2024By Marina Roy

“What sets New Age apart is that its primary sources of inspiration for formulating holistic alternatives are derived from certain so-called ‘western esoteric’ traditions which have long existed in our culture but have seldom been dominant. … the idea is that an inner core of true spirituality lies hidden behind the outer surface of all religious traditions, and that the knowledge of it has been kept alive by secret traditions throughout the ages.”1

One now occasionally encounters esoteric/spiritual knowledge as a respected register within artistic practice. And yet, as recently as ten to fifteen years ago, art historians and critics dismissed artists and thinkers whose work raised engaging questions around spirituality, who spent much of their time seeking ways to access deeper meaning in the world. What changed?

There has been a resurgence of interest in Theosophical works. In 2013, Hilma af Klint’s paintings and drawings began to tour across Europe after lying in obscurity for over a century. In 2015, curator Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev exhibited Annie Besant and CW Leadbeater’s Thought-Forms (1901). The “art world” is now slowly coming around to considering contemporary artworks that seriously engage with spiritual matters. Deborah Edmeades’ artwork is one very important example. The work is uncompromisingly idiosyncratic, mining years of research in the history of Western esotericism, as well as finding inspiration from feminist artistic traditions.

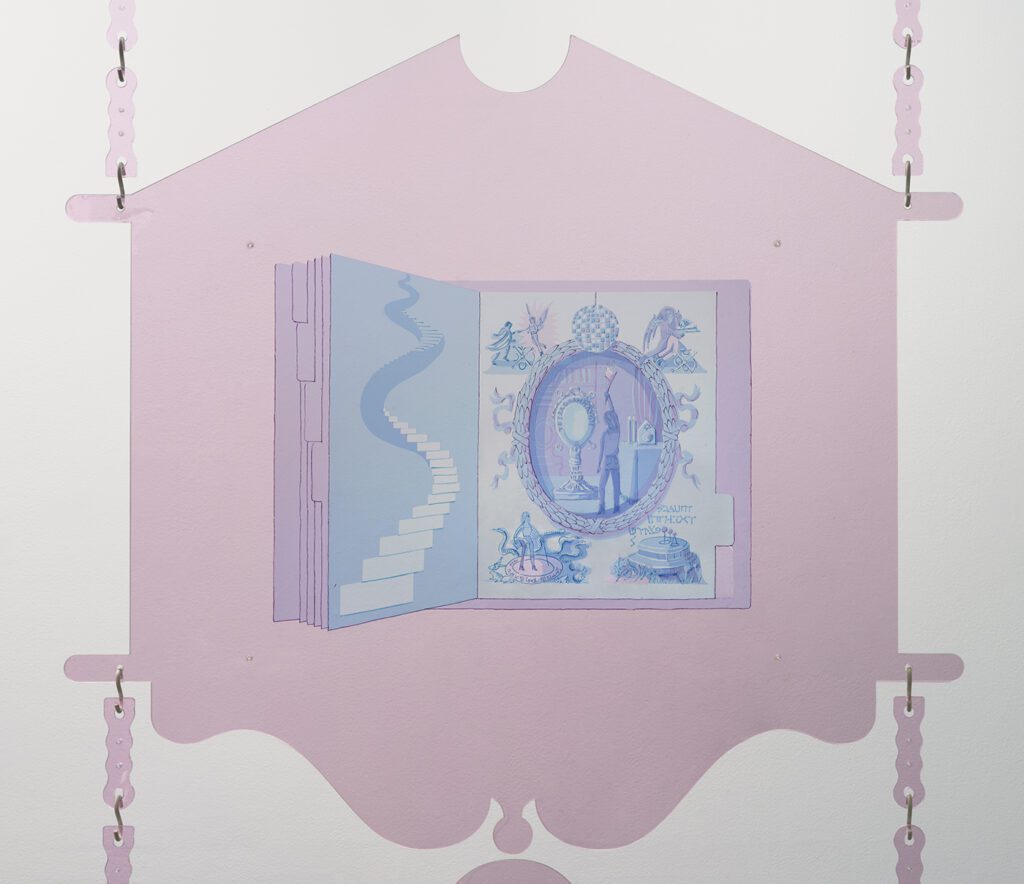

In Debi’s (Teenage) Theosophical Enlightenment Edmeades allegorically narrativizes a spiritual awakening across a series of six acrylic panels. Each pink panel is shaped to mimic 18th-century signage, and has inserted within it an illustrated plate keyed to a primary and secondary colour—magenta, violet, blue, green, yellow, and orange. For over a decade, Edmeades has engaged with Goethe’s colour chart across many of her works, tapping into the mystical qualities and connotations of this spectrum of colour. Edmeades also uses these six colours in a multi-colour tab system within ring binders, thus referencing a colour-coded filing system for organizing research. These colour tabs are also intrinsic to the logic of the six-panel series.

Each of the acrylic panels captures the teenage protagonist Debi (the artist in her youth) theatrically engaged with historical figures and iconography related to western esotericism. In the yellow plate, she sits in a lotus position between two lions, becoming herself a fictional figure inserted into a British coat-of-arms. An owl hovers above, alongside a star and the moon, while British megalithic structures and the Egyptian sphinx and pyramids are situated beneath. This elaborate accumulation of magical structures, emblems, and symbols points to England’s history being founded in pagan religious roots, but also being driven by a fascination with sacred icons of the East (for example, Egypt, India). In the orange plate, Debi is taming a winged Priapus, overseen by a benevolent sun and circumscribed by astrological symbols. The power of her newly discovered sexuality exudes from the work, and the phalluses above the wheat field recall pagan fertility symbols. The green plate exposes Debi mesmerized by the magnetic force emerging from Franz Anton Mesmer’s fingers. Together, the six vignettes playfully ignite a desire to interpret a constellation of historical esoteric symbols and figures that shed an arcane light onto the young artist’s spiritual awakening (and rebellion).

Besides nineteenth-century signage, the works reference other mediums and forms: the stained-glass window, printing (the layering of cut-out forms toward incremental colour gradations), the book, the ring binder (with its colour tab system), ink drawing, film (with the use of coloured film gels), and performance (the artist’s body playing the central role). This layering of media and contexts compliments a layering of histories permeating the imagery—from pre-Christian to Gnostic to Medieval to Renaissance to Enlightenment to Romantic to New Age.

New Age spirituality, while difficult to define and circumscribe, has often found its legitimacy in ancient pagan spiritual forms, all of which had been discredited by Judeo-Christian religious doxa at one time or another. One key difference between early esotericism and the New Age spiritualism of the 1960s-’70s-’80s is a belief in the self as spiritual authority, the belief that every person could access the divine from within oneself. Knowledge could be accessed through direct experience of the body. Alternative spiritual practices put the body back into the picture, promoting a holistic experience of mind-body-spirit. It is important to understand Edmeades’ auto-theoretical, even auto-fictional, panels in this light.

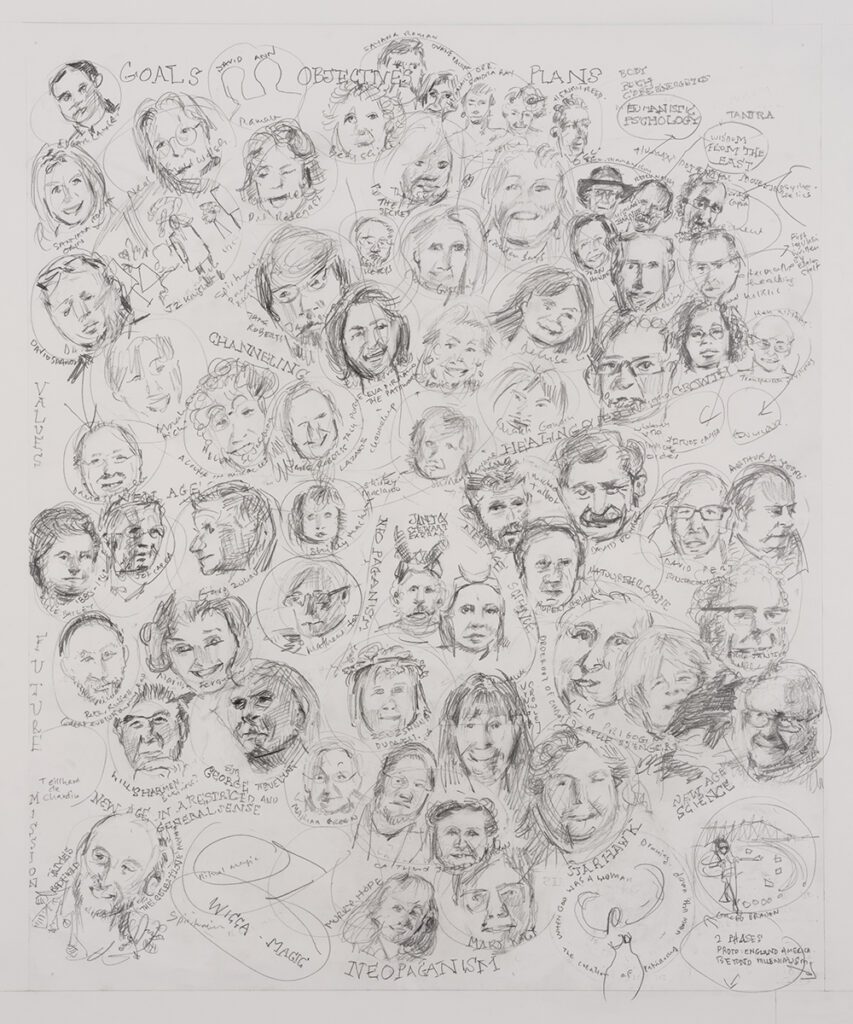

Opposite the six panels in the gallery hung three large graphite drawings. A Preliminary Demarcation of the Field (2024) is made up of loose graphite portraits of leading “New Age” thinkers and authors important to Edmeades’ research. Each miniature head includes name and artist notes on their significance. Heads are clustered around genealogies and affinities. Another drawing, In The Mirror of Secular Thought, contains even more miniature portraits, offering a more sprawling and in-depth genealogy of “new age” spiritual thinkers dating back to ancient times. The drawings are obsessive, displaying a kind of horror vaccui. Alongside these two drawings is an image of the artist’s father’s ring binder; the anamorphic title “My Lifetime Goals Statement” is visible on the front cover, as well as about two-thirds of the first page on the inside. This page includes a drawn portrait of the father at the centre of concentric circles radiating around him (GOD, LOVE, HAPPINESS, WORK, PLAY), as well as the six tabs organizing the binder’s contents: values, mission, goals, objectives, plans, future—mirroring the tabs in the acrylic panel series. This drawing offers yet another layer of context regarding the artist’s background and its relationship with her research into Western esotericism and New Age lineages. The artist’s father had worked in spiritual management training. Within the context of the human potential and positive thinking movements, such training would help individuals reach their full potential, including self-realization within the corporate world. Despite the patriarchal dominance of leaders in this field, assertiveness training for women was part of the artist’s father’s agenda.

The importance of women spiritual figures stands out in Edmeades’ work. In the violet plate Radical Spirits, Debi is spewing ectoplasm from her mouth, which trails up toward Mary Baker Eddy and Helena Blavatsy—two spiritual figures central to Edmeades’ research. Looking at A Preliminary Demarcation of the Field and In the Mirror of Secular Thought, one is taken by the presence of so many women being leading spiritual figures and thinkers. Contrast this to more mainstream religions, which are dominated by men—a history grounded in women’s oppression such as women being persecuted as witches thus having their community of knowledge silenced by the Church. In the 19th century, women were not allowed to speak publicly, but in the context of spiritualism, women went into trances and spoke. They gave voice to invisible spirits and, by extension, internal desires. They spoke in favour of free love, abolitionism, equal rights, and freedom.2

While the aesthetic accumulation of signifiers is what might first seduce the viewer, it is Edmeades’ assemblage of esoteric research linking early women’s rights movements and alternative forms of spirituality that makes the most striking intellectual impact. While playfully dramatizing the artist’s coming of age, the work transcends the personal, resonating in the present day as finding alternative ways of being, and actively resisting an increasingly precarious commoditized world.

- Wouter J. Hanegraaff, “New Age Religion and Secularization” (Leiden: Numen 47(3), July 2000), 292.

- Ann Braude, Radical Spirits: Spiritualism and Women’s Rights in Nineteenth-Century America (Bloomington: Indiana University Press), 2001.

Debi’s (Teenage) Theosophical Enlightenment ran from January 13 – February 17, 2024 at Afternoon Projects in Vancouver, BC.

Feature Image: The Hermetic Revival of the 19th Century, 2024 by Deborah Edmeades. Photo courtesy of Afternoon Projects.