The Beautiful Corpse: Tamara Henderson’s Season’s End: Out of Body

25 April 2018

by Christine De Vuono

Approaching Tamara Henderson’s Seasons End: Out of Body exhibition in Oakville’s Centennial Gallery, one is greeted by a display reminiscent of an ethnographic collection of an ancient culture’s esoteric regalia and artifacts. The collection of robed figures stand in a dense, haphazard formation, curiously pulling the viewer into their maze-like world. Dimly lit with tempered overhead lights of blue, magenta and green, the costumed figures impede the viewer’s ability to examine the exhibition as a complete entity. Tamara Henderson’s final rendition of this ever-changing, internationally-shown installation draws the viewer into a dreamlike world of talismans and detritus, impermanence and demise, each holding equal status within the display. Henderson attempts to create an exhibit of otherworldly and spiritually infused artifacts created from her personal reference points, ultimately rendering them with uneven success.

Keeping with the overarching theme of impermanence, the Oakville exhibition juxtaposes the aura of the museum—with its subdued lighting and reverence for the ancient collection—with Henderson’s intentional distressing of her objects, displayed mainly through textural examples of brokenness, decay and faded surface qualities. According to her artist’s statement, Henderson’s artistic intent for the show was focused on the temporality of existence, spirituality and mysticism as visualized through objects and fabrics collected during her travels to Greece and the Bay of Fundy; readings including The Tibetan Book of the Dead, The World of Fairy Tales, and Helen Keller’s essays on living in a tactile, yet dark and silent world; and music by Bernie Krause. These references also shed light onto the artists’ aesthetic choices, focusing on themes of the passage of time, death, and that which is beyond our corporeal understanding.

Upon entering the gallery, Henderson’s scattered sculptures seem to be awaiting the viewer’s arrival under subdued, tranquil lighting. The “figures” that make up the majority of the exhibit stand sentinel throughout the rectangular room. Formed with copper armatures—flat with arms outstretched—they don robes that drape in a kimono-like fashion. Furthering the anthropomorphization of the figures, additional accessories add to their individuality, with some in robes adorned with sea shells and twine while others have ribbons, journals, and scraps of paintings taped to their cork “shoes”. Unlike actual displays of culturally important regalia, in which the supports are only employed to accentuate the ideal viewing of the clothing, Henderson’s copper frames, cork shoes and headpieces are as much a part of the figures as the robes themselves, as they are adorned with unique mementos reflecting each sculpture’s personality. Without the museum barriers of vitrine glass between object and viewer, the figures impose their over six-foot tall presence upon gallery-goers, demanding autonomy over their space by limiting what one can see beyond, as well as how one navigates between them. There is also a sense of melancholy in the way the materials were chosen for each figure—some seem weighed down by their multiple and overflowing pockets, or hold evidence of expended labour in their elaborate hand-embroidered details. Oftentimes, the collections of adornments do not seem entirely congruent; glass eggs, smooth stones, and magnifying glasses in place of heads, and handmade, seemingly filled journals strapped to the cork feet give the impression of a silent pleading to be noticed, or for someone to bear witness to the glory that once was.

Each of the figures is distinctive. Some are obviously so, such as Eye Witness (2017), an assembly of three figures whose robes have large eye shapes embroidered symmetrically onto their right and left panels. Another piece, Editor in Suitcase (2016), with its multiple pockets full of coloured pencil nubs, an editing manual and paper clippings, seems straightforward as well. However, for others in which the material messages are more subtle, either Henderson has her own personal logic or the viewer needs to work a little harder to decode the works’ themes. It’s as if each figure holds site-specific signifiers to different places, pursuits and values that need to be scrutinized not only individually, but also as a collection. If there is one common element that binds the figures, it’s a deliberate distressed or aged quality of the materials—unfinished threads hang, paint is intentionally faded, and clay details are indented with deep cracks, all of which seem to reference age and desiccation. Throughout my viewing experience, I also imagined an alternative narrative in which these aging details were the result of a distracted artisan who could not be bothered to attend to those trivial bits of care.

Along with the figures, Henderson created five wall hangings and two sculptures to complete this final iteration of her exploration of the spiritual and the impermanence of the natural. The wall hangings compliment the robed figures with their earthy palette of dyed fabric, cracked clay castings and ornamentations of rusted metal grids and coils. Just as the figures chronicle the themes of talismans and detritus, the hangings further this narrative by adorning the walls with faded designs, as though they were tapestries originally made for somewhere else—stone walls of a fortress, perhaps. They hang sporadically on the back and side walls beyond the robed figures, each separated from the others. The naturally dyed fabric and visible hand-sewn stitches give evidence of handmade labour in the same way as the robed figures, but without their personalities. Overall, the hangings have some interesting features, such as the metal grid-like additions to their fabric, but not enough to keep one with them for long.

Finishing the exhibit are two sculptures. On the back wall stands an apparatus that gurgles and clicks away monotonously. The gallery pamphlet describes Bar of Body (2017) as “a winged figure that breathes in and out with the aid of a mechanized breathing apparatus,”(1) but it looks more like an ancient pinball machine with splayed legs. Although the description in the brochure does not quite suit the object itself, its intricacies are interesting to explore visually and aurally. In the upper portion of the apparatus, large bellows create the mechanical breathing, generating the sound of an old, weather-beaten pair of artificial lungs. The feeling of listening to an antiquated being is accentuated by sounds of liquid being drawn through tubes, lights from within the body of the piece that attempt to illuminate illegible film strips, and a five foot stretch of cushion that harkens to the idea of a fainting couch. The exterior of this “couch” is covered in hand-sewn faded fabrics and is decorated with dried clay, bits of ribbon and a glass globe housing dried herbs, desiccated as though through neglect. The sound of water being drawn up a tube made me hunt for the source, following it until I was unable to go further as it meandered into the apparatus. The questions for what purpose? and where is it going? led me to spend time scrutinizing the mechanics to see if they offered an explanation or, more regularly, frustrated my exploration with their lack of information or discernable function. This frustration was not unpleasant, as it often led to musing over little puzzles with no apparent need for solutions.

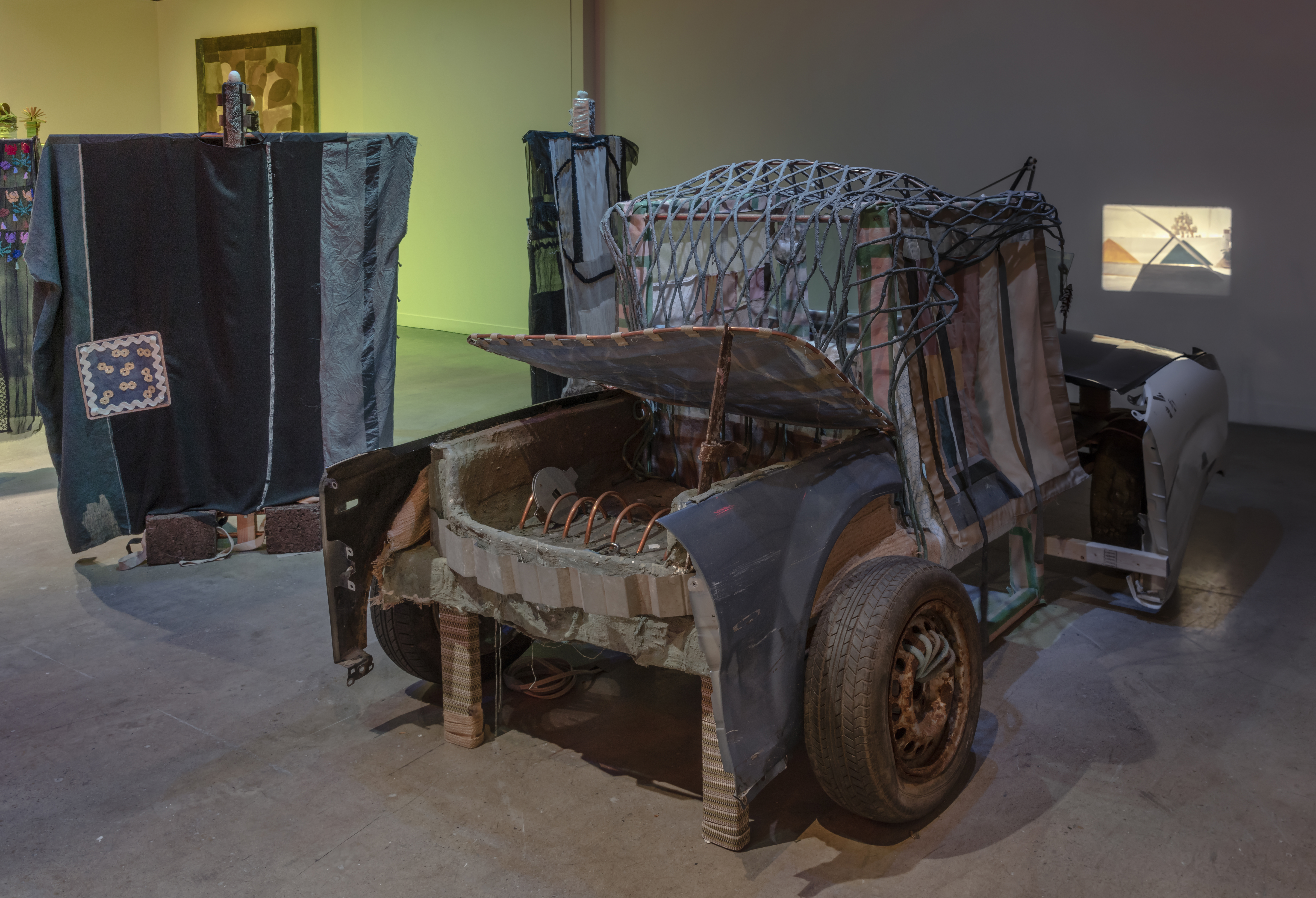

Along with Bar of Body, Henderson’s exhibit contained another non-robed sculpture. Seasons End Vehicle (2016) is a car à la Gilligan’s Island (if the shipwrecked crew had a few pieces of sheet metal to adorn their tropical vehicle). Crocheted seat cushions and netting are hung from a wooden frame in place of car doors and windows, which clash with the metal hood and wheel casings to create a contraption that seems to have been made from a vague idea of what a car should look like. On top of the hood of the car sits a film projector, which is loaded with a reel of film that could not be coaxed to function. If there had been indications that this mechanical projector was not meant to work, it would have fit into the overall feeling of broken mechanics, but the gallery staff’s attempts to get it functioning spoke instead of a problematic installation. This felt frustrating as Henderson’s intended effect was not realized and therefore could not be experienced. Yet if it had just been left broken purposefully, I feel it would have melded into the overall oeuvre of the exhibit’s message of impermanence and belief that even if broken, there is still value in what has passed.

These two sculptures sit on opposite sides of the back wall, beyond the central maze of robed figures. Both works’ sound components allow the visitor to hear them before seeing them: a repetitive, mechanical breathing sound comes from Bar of Body, and the sound (ideally) of a 16mm film projector comes from Seasons End Vehicle. Both works are supposed to weave into an ethereal soundscape playing from speakers at the front of the gallery. However, over the course of two visits to the exhibition, the film projector could not be made to work either time, the kinetic portions of Bar of Body were broken during the first visit and the soundscape was not playing during the second. Snatches of the intended ambiance could be imagined, but the execution of the mechanical portions of these sculptures and recordings left much to be desired. A more successful presentation of the work may have been hindered by Henderson’s overall dedication to the handmade and vintage throughout the entire project. It would have been more satisfying if everything worked without drawing attention to its proficiency, or if it had been purposefully made to repeatedly snag like a broken record.

Wanting to know more about the foundations of Henderson’s narrative, I read the brochure supplied with the show and referred to the gallery’s website. Both mention a trip to Greece and the Bay of Fundy, but the purpose of these travels is not expanded on and seems unsatisfying for a show that proclaims “reference to dreams, fairy tales, the spiritual realm, and the natural world”. (2) Writing that the fabrics and plant dyes had come from these places weakens the untethered feel of the show. It made me question why Greece, and why the Bay of Fundy? I started wondering whether the show is linked with these places (aside from the materials’ physically coming from there) or if they are akin to padding one’s resume. The readings Henderson used to inform her practice make more sense to the timbre of the show, since they explore sensory experience, otherworldly investigations and that which is beyond what we can experience in our day-to-day lives—elements that could inform any culture’s development of regalia and spiritual devotion—but they seem sparse as well. When these references are coupled with two seemingly disconnected places, the otherworld diminishes and our real world asserts itself in an incongruous way.

Each time Seasons End is shown, Henderson responds to the gallery and geographic site in a way that simultaneously speaks to the location and negates the option of showing the work again in the same way. For the Centennial Gallery exhibit some elements worked well, such as the robed figures and Bar of Body sculpture, and others did not. This being said, the overall final show was worth the visit. Having not seen the other exhibits, I can only surmise that different show locations with altered elements would create different experiences. However, the personalities of each of the pieces keep the essence of the show intact by maintaining feelings of transience, an awareness of decay and the temporal reality that nothing lasts forever.

1. Tamara Henderson, Seasons End: Out of Body (Oakville. Centennial Gallery, 2017).

2. Oakville Gallery website. Information gathered March 5, 2018 at: http://www.oakvillegalleries.com/exhibitions/details/186/Tamara-Henderson

Season’s End: Out of Body ran from September 24 to December 30, 2017 at Oakville Galleries at Centennial Square.

Feature image: Installation view of Season’s End: Out of Body by Tamara Henderson. Photo by Toni Hafkenscheid, courtesy of Oakville Galleries.