Truly, Madly, Deeply; A Case for Vulnerability: In Conversation with Beau Gomez

5 February 2023By Nawang Tsomo Kinkar

How does one evaluate the authenticity of an artist’s work? Is it the artwork itself or is it the engagement with it? In this late-capitalist, image-driven world, what does meaningful engagement with contemporary photography look like? How do we value generosity, connection, depth and above all—truth?

I am often at a crossroads between admiring an artist’s body of work at face value—the aspects that are detectable on the surface, the interpretations that comfortably linger in the presentation space—and how I might nurture this relationship between artwork, artist, writer, and as a human being. It therefore came to me as no surprise when I fell in love with Beau Gomez’s El Angel. I fall in love so easily, and photography can be such a beautiful thing. However romantic this may be, it’s important to remember that love too can be fickle, and photography, by its very nature and science, is also a fickle phenomenon.

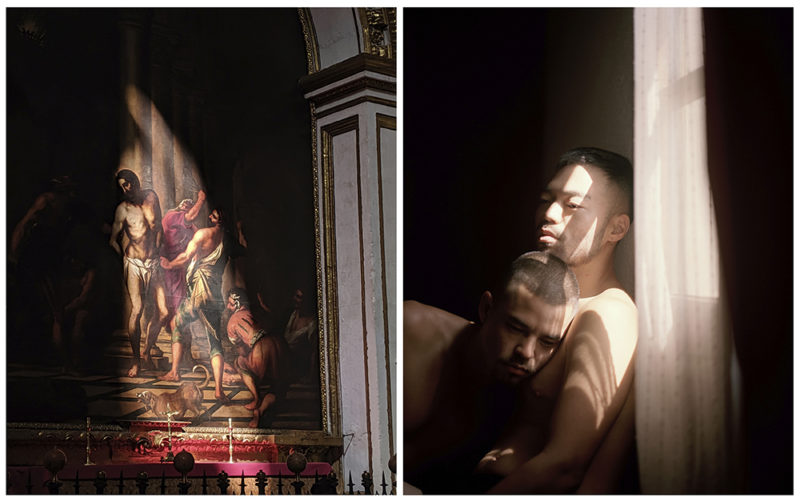

At a coffee shop in Toronto’s Annex neighbourhood, Gomez guided me through El Angel with such patience, precision, and vulnerability that I thought, I don’t deserve this. Conceived during a European summer trip with two friends, El Angel is Gomez’s first large-scale project that was exhibited from October 20th to November 26th, 2022 at Artspace Gallery, a TMU artist-student-run centre inside Toronto’s beloved 401 Richmond. Consisting of photography, video, ephemera, and text, the series chronicles varying cues of companionship and introspection between three friends. Derek and Ray, visibly the main muses of the project, are portrayed in moments of sheer tenderness, which could only be accomplished by someone who truly saw them. Alongside these notions of joy and play, Gomez allows us glimpses of frank and emotional conversations regarding their shared and differing experiences as queer Asian men. Captured in film, the subjects’ conversations are presented in videos where the friends are seen laughing, dancing, and being. In motion and fully engaged with the world around them, El Angel is boundless in its ability to tell a captivating story of coming home to oneself. And perhaps more audaciously—coming home to one’s queerness.

Beau Gomez: Summer of 2019 was a marker of a significant time in my life. Openness and disclosure are integral aspects of both El Angel and my practice. El Angel is quite personal and revealing. There are varying layers of emotional nuance and gravity in the work. This has been a thoughtful exercise in putting together a body of work that says so much about a person’s vulnerability, without giving too much away.

During that time, I had known Derek for over eight years and Ray (who I met through Derek) for just under a year. We have collectively fostered a deep, affectionate bond and I wanted to take the trip as an opportunity to make a project, though I didn’t necessarily know what it looked like then. All I knew was that these were people—and fellow queer Asians at that—that I had really close friendships with. It also seemed like a good opportunity to check-in with each other. I simply documented the trip with my film camera, phone, and zoom recorder as much as possible. When I returned back home, I had this plethora of imagery and footage, and that’s when I started thinking about how to make sense of it all.

Nawang Tsomo Kinkar: Why was it important that you record and archive the intimate conversations? You spoke about how painful some of these revelations were, and I’m wondering how you came to decide that you wanted to save these difficult memories. What role(s) did these recordings serve you throughout the making of El Angel?

BG: I felt that the conversations really grounded the work, especially in its intersection with the video footage. They unpacked a lot of common—and uncommon—threads between us: How were we doing on our own or with each other on an internal level? Were we aligning? Were we not aligning? Were we fulfilled, were we in a good place? We reflected about ourselves in ways that we had not done before: our Asianness, our queerness, and how we navigated these identities. We opened up about our struggles, our familial and cultural upbringing, and how these all shaped and currently shape us. I admit that for a while I did not revisit the recordings, because there were many emotionally intense moments, and were therefore hard to listen to.

As a portraitist, I have always been curious about the ways people express and perceive themselves. Being a photographer has allowed me to get to know people more deeply. Having the opportunity to do this with people I trust, and being able to document it, is a beautiful thing, and the added layer of conversation within this process can heighten the emotional depth of image making.

With Derek specifically, he is someone that I am very close with. We have a friendship that refuses to shy away from anything. We’re very naked with one another—and I mean that both in the literal and emotional sense. We’ve been through a lot together, and I felt that the trip was an opportunity to honour and celebrate our relationship.

NTK: Often there is an endless possibility of adventure associated with the notion of travel. How did travel, and being in another environment which was not your home, effect El Angel?

BG: With travel there is a heightened sense of self, adventure, and an openness that comes forth when you are not in your comfort zone. Being in unfamiliar places challenged us to dig deeper. Granted, this can happen at home, but because we were travelling, we were not thinking about our day-to-day obligations. We had more freedom and it enabled us to let go of restraints. It somehow gave me the time and opportunity to confront the harder parts of myself. I think this was the driving force behind me wanting to connect and strengthen our relationships—to bear witness, and ultimately, for me to heal. Being in close proximity with two queer, Asian men, almost everyday…I knew it was special and I wanted to connect with them on a level that perhaps we had not been able to do before.

NTK: From the many striking images of Ray and Derek—both the playful and commanding counterparts—to the palpable sensation that I feel looking at the idealized version of the male figure (Christ) in the image of Michaelangelo’s fresco, to the statue of Hermes and the little figurines of cherubs peeking out from the leaves (which remind me so much of Derek and Ray in El Angel), the gay, male body is a very visible aspect of the work. What was this process of experimentation like?

BG: I have always intended to convey my friends’ bodies and presence in a poetic light. I aim to present the queer, Asian male body in an intimate way. This project is ultimately about surrendering ourselves to the process, to giving in to one another. It’s quite rare to see Asian men exhibiting affection towards each other, much less in a public way, and so I wanted this work to illustrate a sense of shared tenderness and gentleness, both within the images and the dialogue.

NTK: So much of our society shows us that softness is something that is weak, when in fact it is something that allows for bravery. In her book, The Will to Change: Men Masculinity, and Love, the late bell hooks writes: “The masculine pretense is that real men feel no pain.” hooks argues that softness and masculinity is often polarized in Western culture. This is the same heteronormative, patriarchal culture that Asians also operate within. In the context of Asians, there has always been a kind of violence that is inflicted upon our bodies and sensibilities. Asian women are exoticized and Asian men are ostracized and often looked upon as “not man enough.” How do you reckon with notions of masculinity, gender, and Asianness in your work?

BG: Patriarchal masculinity remains prevalent within and beyond the queer community. Asian men, queer or otherwise, particularly within a Western lens, were historically perceived to be lower in the social hierarchy and desirability because they were deemed submissive, not attractive, or not masculine enough. Furthermore, as men we have been conditioned to keep our emotional selves locked up, to preserve our “manliness.” These are things I constantly contended with growing up, even to this day. In my work, the notion of the masculine self being raw and vulnerable was something that the three of us unpacked, notably the difficulty to express ourselves in ways that allow for emotional openness, and challenging the structures of our own preconditioned masculinities. For a long time, I associated vulnerability to weakness. I also come from a very stoic, tough-loving Filipino family; we never talked about nor were we ever encouraged to express our feelings, but when I met Derek, it surprised me in how much ease he has with opening up. He really is not afraid to express himself as freely as he does. He has taught me greatly about how vulnerability can be empowering, even if it’s fraught. This project ultimately anchors itself in the strength to be vulnerable, grounded in our Asian queerness in spite of our difficult pasts.

NTK: Our heteronormative and hyper-masculine society makes one feel like so much is at stake when their vulnerability is in question. When we met, you spoke about being influenced by Vietnamese-American writer and educator Ocean Vuong, who in a recent interview at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, graciously offered approaching vulnerability as power. What was it like coming to terms with sharing such a raw and personal story?

BG: There is so much about our shared storytelling that touches upon deep, and at times dark, moments in our lives, and for a while I refrained from putting this work out because I wanted to protect just that—I wanted to protect theirs and I surely wanted to protect mine. I knew I had to let time and patience usher me into a headspace where I could feel empowered by the work, and the realm of promise and possibility it held for me and my friends.

I spoke earlier about disclosure. I refrained from presenting this work because a big part of our conversations revolved around my HIV diagnosis. Around the time of this trip and when the project was taking place, I was still buried deep in my self-doubt and shame. I had a completely different perspective of myself then. I can’t say I have fully reconciled with my status, but with time I certainly have taken greater strides, in that I am more forthcoming with opening up given the opportunity, and I can speak more openly about where I am with coming to terms with my status, embracing my discomfort, and being at peace with the fact that this is a lifelong process of (un)learning and reconciling.

NTK: More recently, El Angel exhibited at Artspace Gallery in Toronto and from our past conversations, I recall that you had a slew of ideas on how you imagined this work would be presented. Now that the exhibition and the accompanying programs have concluded, I wondered if we could reflect on these past events. How was it finally releasing the project into the world in such an official manner? And what did you take away from these engagements?

BG: It has been an overwhelming, ultimately rewarding experience to show El Angel as a living, breathing body of work. It allowed me to experiment with embodying emotionality within a space, from the free-flowing nature of the delicate silk prints, to the enclosing sounds of environmental noise, of voices breaking, and even silent pauses in the dialogue. Upon entering the gallery, you become immersed in this raw yet tender surrounding. The large-scale audiovisual projection (consisting of the audio and video recordings) is so confronting and sensorial as though you are a direct witness to a deep conversation. I wanted the show to convey the nostalgia and memory of this incredibly heightened, pensive time and space that myself, Derek, and Ray were in.

The show also welcomed the opportunity to exercise shared vulnerability in ways that I never thought would empower me so significantly. I had the privilege of inviting support groups living with HIV to see the exhibition (as organized with ACT, ACAS, and Queer Asian Youth in Toronto) and subsequently have a post-show discussion with them. I am so thankful and humbled by their shared resonance towards the work and to my story. It’s one thing to share your experience with a friend, a student, or a passerby, but to relay my story—particularly my journey of living with HIV—to someone who has gone through or is currently going through the same thing I did…it really means a lot to me. It has become an even stronger reminder of how anchored I am in my core motivations as an artist, as someone who fosters community and a sense of belonging.

- bell hooks, “Wanted: Men Who Love,” in The Will to Change: Men, Masculinity, and Love, (New York: Washington Square Press, 2004), 6.

- Louisiana Channel. (2022, September 6). Ocean Vuong: “When I write, I feel larger than the limits of my body” [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u5NuCrAkjGw

El Angel by Beau Gomez ran from October 20 – November 26, 2022 at Artspace TMU in Toronto, ON.

Feature Image: Men with fans, 2019 by Beau Gomez. Photo courtesy of the artist.