Unbound from the Limitations of the Sex Worker Archive: In Conversation with Daze Jefferies

22 July 2024

By Brody Weaver

A thousand kilometres apart, but connected between Halifax, NS and St. John’s, NL through video-call, I had the pleasure of interviewing artist, writer, researcher, and educator Daze Jefferies in late March of this year. Her multi-disciplinary practice engages creative research into the histories of trans women and sex workers in Ktaqmkuk: (Newfoundland). Jefferies’ work and research has emerged as a waypoint of queer and trans historical inquiry and archival intervention in this region. An artist’s journey into the archives (be these brick-and-mortar or web-based) surfaces alternate feelings and expanded lines of inquiry than we often see in traditional historical research. Unbound from the obligations of non-fiction, material traces of the past have instead become a starting point for speculation and worldmaking in the artist’s hands.

In our conversation, we discussed growing up in rural, east coast communities connected to the fishing industry, the relationship between the sex trade and fish trade in St. John’s, the delicate act of encountering trauma and violence in the archives, and what an anti-colonial approach to trans women and sex worker histories demands. Jefferies also generously shared the process of creating two artworks, dream zones hormones undertones fish bones (2022-23), and resurfacing you torn-together (2023), as well as new reflections on her first major solo exhibition, stay here stay how stay, which ran from January 20 – April 7, 2024 at The Rooms in St. John’s.

***

Brody Weaver: I feel like I have this synergy with you, which might sound strange, because this is the first real conversation we’re having, and it’s on the record. We’re both trans women who grew up in rural places and make art that works with the archive, memory, and trans and feminist histories. Even more, those rural places that we’ve grown up in are on the water. For you, that’s the Bay of Exploits in Ktaqmkuk, colonially known as Newfoundland. For myself, it’s a small fishing village called Port Stanley on Lake Erie, in what is colonially known as Ontario. These places as we know them are a result of settler colonialism and resource extraction, in particular from the fishing industry. I know that the ocean as a place, being, and concept has been formative to your work. Hopefully, we can start there: the idea of place and what it was like to grow up where you did, and how that formed your identity and your art practice.

Daze Jefferies: It’s so nice to have this conversation with you! Water shapes my childhood memories: always playing on beaches and cove cliffs, dreaming about mermaids, sucking and crunching on tiny bits of icebergs washed ashore in late summer, and boating and fishing with my family in the archipelago. I am a sixth-generation settler who grew up on the northeast coast of Newfoundland, the ancestral territory of the Beothuk, who were dispossessed of their land and culture. In contrast to the joy in my memories as a child, the Bay of Exploits is also a place of loss, genocide, and heavy resource extraction. The water holds that history too. I’m trying to respond to this conflict in my work.

I feel like rural queer and trans life was in flux throughout the early 2000s. At the edge of the Atlantic, I lacked physical and community resources, but I had Internet access and a gay best friend. My parents were always supportive of my art practice, and I spent a lot of time drawing, writing, taking photographs, and making music/sound art, which truly kept me going as a genderqueer youth in the outport. Queer and trans aloneness is a dominant theme in Newfoundland and Labrador archival materials, and I think that a lack of intergenerational connections makes our lives challenging. Trans women and sex workers have historically had different terms of survival in rural and coastal places. There are silences and absences, but I also see reflections in culture, language, and the ocean. The settler colonial culture of Newfoundland includes a lot of gendered and sexual imagery. For example, sea urchins are colloquially known here as “whore’s eggs.” I’ve been evoking some of that language in critical and creative ways, and being a trans sex worker influences my approach of response and reclamation, which can communicate the power dynamics differently. The idea of “fishiness” has also shaped my work for a number of years. Articulating fishy language, which I understand as uncontainable expressions of t-girls and sex workers, and immersing it into queer and trans life in a rural oceanic environment, has offered playful ways of narrating and embodying trans womanhood in Newfoundland.

BW: You’ve worded it before as “feeling fishy,” and that verbiage is so brilliant because it’s funny but so poignant. “Feeling fishy” means there’s something beyond the surface. There’s something going on here. What you’re saying about gender roles in rural places as masculinized due to particular forms of physical labour is so, so relatable. I don’t know if this is relatable for you, or if your family was involved in the fishing industry directly, but growing up I found that there was such a divide between the people who go out on the water to do the fishing, and the people who deal with what comes back from the water. You know, processing the fish and all of that.

DJ: Yes, absolutely. My family has been working in the fish trade since the mid-1800s and my parents were the first generation to move beyond it as their primary source of survival. My oldest sister is a fisherwoman. It’s arduous, precarious, and vital work. There was actually a major protest in March that addressed some of the financial and political tangles shaping the present-day fishery. Fish harvesters and plant workers are the backbone of many communities in Newfoundland, and the class divides are significant. I’m interested in narratives of extraction, abundance, and loss that surround the historical fishery. Some of my research-creation has been in exploring connections between the historical fishery and sex work, or prostitution,1 in colonial Newfoundland. They have been interdependent for hundreds of years. I’ve also been thinking a lot about resource extraction, which can be understood as a form of violence against ocean life, and its role in shaping gender-based violence experienced by sex workers, throughout colonial history. In my current work, I’m trying to re-story links between them while holding the powerful to account. Much of the historical record doesn’t privilege the voices of fisherfolk or sex workers, but features the male merchants, which of course is based in class inequality and patriarchal domination. So, I’ve been trying to refuse the power of the merchant to instead sit with the realities that fisherfolk and sex workers have in common. “Feeling fishy” as queer/trans vernacular becomes especially resonant in this context.

BW: Can you talk more about this interdependence between the industry of sex work and the industry of fishing?

DJ: Newfoundland and Labrador settler historian, Paul O’Neill, published a major text called The Oldest City, which is a history of St. John’s.2 He notes that sex work, or transactional sex, can be traced back to the 18th century, and possibly earlier, but it remains speculative. At that time, life in the city revolved around the Harbour, which is also where the working girls often plied their trade. According to him, fishermen regularly occupied “houses of ill-fame”3 which is such an expressive term. The first appearance of a sex worker in the colonial historical record is from 1757, and she’s a young woman who steals money from a drunken sailor. She is later apprehended and punished before being banished from the island. Her name is Elenor Moody. The rest of her life seems to elude the historical record from that point on, and I’ve always wondered what her future held. She emerges as an unruly girl doing what she needs to, but her story introduces this transactional and interdependent link between men working on the water and local women’s sexuality.

The harbourfront has remained a key site of sex work history for hundreds of years, and some girls still work around there today. I did when I was younger. I remember the first time a client brought me there late one night. I didn’t have any older sex workers in my life, and I didn’t know much about the Harbour’s “whorestory” at that point, yet he guided me towards it. The historical relationship or intimacy between fishermen and sex workers in outport communities is less documented and remains a matter of conjecture, but many present-day clients still work in oceanic extractive industries like the fishery or oil fields. The coming and going of men on the water and practices of sex worker survival seem to have sustained each other for a long time.

BW: This historical understanding of water, bays, and docks as points of trade and transaction and movement of people and goods, willing or unwilling, is historically significant to the East coast of so-called Canada, especially in the history of transatlantic slavery. Charmaine Nelson, a renowned Canadian historian of art and visual culture who focuses on Northern enslavement, researches the archival traces of enslaved Africans in this region and the limits of the colonial archive. Nelson has pointed out, alongside other historians, that the most detailed description of enslaved people in the colonial archive is through notices in newspapers marking them with fugitive status for taking their own freedom.4 I see an overlap there, in the colonial archive and a response to it, with how you’re talking about sex workers and trans women appearing in the form of legal documentation. When you began to search out these histories, where did that take you? Literally, where did you have to go to find that knowledge, and, conceptually, where did that take you and your art?

DJ: Absolutely. The archive has most often been an enclosure. As an undergraduate student, I developed a deep interest in feminist and anti-colonial approaches to folklore, history, and archival work, which shaped my journey to know more about trans and sex worker historical lives. I’ve researched in archives, listened to rumours, scoured the web, and conducted oral history sessions with older queer adults. A lot of the historical records are shaped by violence. I became a sex worker at the beginning of my social and medical transition, and I desired a trans, sex-working mother figure who could care for me and keep me safe. I knew several older trans women, but none of them were sex workers. My trans sister Violet Drake, who’s also an artist and writer, has always held me up. I think that intergenerational relationships within queer and trans community in Newfoundland are shaped by a number of factors, including outmigration, stealth and secrecy, and of course loss and death. I turned to archival material as a way of dreaming towards a withheld past. Beyond the medical and criminal-legal records and sensationalized media reports, I had been looking for ordinary stories of trans women and sex workers in archival collections, and they were elusive.

At the time, as a young doll looking for guidance and support, I considered it to be a community loss, and it took a while before I could rethink that silence as an intentional choice. I soon became interested in counter-archival practices that made room for speculation and desire. I still believe that intergenerational relationships are possible, and that marginalized cultural knowledge survives somehow. I’ve looked through a lot of personals ads in newspapers from the late 20th century, and there are no explicit t-girls in them, but there are hints, which are good enough for me. The first archival “evidence” of trans sex workers emerges from those personals ads in the early 2000s. I’ve been reflecting on how archival traces come to be, but also how the needs of trans women and sex workers escape those forms of documentation. So, I’ve turned elsewhere, to water, as a counter-archive.

St. John’s Harbour can be understood as one of the oldest sex work strolls in colonial North America, because St. John’s is one of the oldest colonial cities. The presence of both the stroll and the few archival records encourage me to believe in the power of speculation. I really like this quote from Tourmaline, “displacing the archive as a place of truth,”5 which I’ve been referencing a lot lately. The work of Tourmaline, Saidiya Hartman, and Jules Gill-Peterson, in particular, have really shaped my thinking about historical lives that refuse archival visibility and possession to instead enact what Hartman refers to as “practices of freedom.” Speculation, belief, rumour, gossip, and archival records interflow throughout trans and sex worker histories. For me, an intergenerational imagination becomes a significant way of establishing relationships and connections. Thinking about the speculative might-have-been doesn’t foreclose possibilities of trans and sex worker survival, especially in a rural, coastal environment. Speculation might also offer a way of becoming closer to practices employed by trans women and sex workers to purposefully evade archival capture. I want to hold on to those desires and to honour them in my work, to stay with the knowledge offered by water, time, and dreams.

BW: Anytime there’s an archival trace of something, you speculate that there are many traces that could have been there that are not. A lack of documentation of someone is not always something that is unfortunate and sad, but rather can be evidence of empowerment in terms of refusal and “avoiding capture,” as you say. I think this is so important, and I think that idea is lost in a lot of archival projects and art practices that make attempts at recuperating the archive, or trying to recover from the colonial archive examples of trans women from the past or sex workers from the past. This can inadvertently bolster the legitimacy of the institutional archive and reproduce its boundaries. At the same time, I’m so empathetic. Growing up as a genderqueer person, I understand the power that seeing examples of someone like you in the place that you’re in can have. That is why I see this speculation that you engage in, in terms of the archival and historical, to be so powerful and well done. What I think might be my favourite work of yours is a video called dream zones hormones undertones fish bones (2022-23) where you imagine a dialogue between a younger trans woman and a transsexual grandmother. It is presented through emails, and I imagine it as a fictional conversation but probably steeped in some very real experiences.

DJ: Over the past few months, I have been articulating that this work isn’t about representation, but it is about response. What can be offered through responses to archival bodies or encounters with archival materials as opposed to desires to represent the past with fraught terms of queer/trans visibility in the present? This questioning guides my relationship with archives. dream zones hormones undertones fish bones (2022-23) was created as part of a residency at Struts Gallery in August of 2022. I had been doing digital archival research and thinking about trans histories of the Internet. There’s been some really cool work exploring the trans Internet, such as a book by Avery Dame-Griff,6 an article by Rhea Rollmann,7 and also the @sexchange.tbt Instagram account that posts iconic screen grabs and archival materials.8 What does it mean to activate a recent history that trans women in particular have co-created in order to be closer, to build relationships or sisterhoods? I was using the Wayback Machine for a number of years as a way of “hacking” the archive, and it made me question the ethics of accessing intimate digital communications.

During my grad studies, I remember scrolling through a website for Newfoundland Gays and Lesbians for Equality (NGALE), which was the main queer organization in Newfoundland and Labrador from the mid 1990s to the early 2000s. On one of their forum pages, they hosted a link to a digital trans support group in Atlantic Canada that was created in the late 1990s by a trans woman in Halifax. I had talked to a small handful of middle-aged trans women from Newfoundland, who shared their experiences about using the Internet at that time, and how having access to an online community really changed their quality of life, so I was imagining the experience of being from a coastal or rural environment in the 1990s and using a new technology to establish a broader trans sisterhood and community. In some ways, it wasn’t so different from my own experience navigating gender questions online as a teenager in the late 2000s. Those questions guided dream zones hormones undertones fish bones (2022-23), which is a fictional email exchange, but it’s also a dream with playful poetic imagery and a whimsical rhyme scheme in places.

The voices were created using AI (my first and probably last time), and I edited them with a vocoder. Adding ambient synths and a field recording of waves became a way of setting the conversation outside of linear time. Two netted mermaids reach toward each other at the beginning and ending of the piece. It was comforting to imagine this dialogue between a young trans girl and an older TS mother figure, and to emplace archival fragments of Canadian trans history within it. I wondered what it might have been like for young trans girls in Atlantic Canada to receive a copy of gendertrash from hell in the 1990s.9 I also make reference to a speculative gender identity clinic at Memorial University in the 1970s. I’ve explored some of these questions with Rhea Rollmann, another trans woman writer and journalist in Newfoundland. We haven’t been able to confirm that this clinic actually existed. There’s one trace of it published in Rupert Raj’s FACT newsletter Gender Review from 1978—a list of four gender identity clinics in Canada, and the one in St. John’s has a question mark next to it, which has always fascinated me.10 Revisiting Tourmaline’s quote, archival documents aren’t always records of truth, but they can offer just a trace that makes room for dreams and speculation in the absence of firmness. They can also encourage us to respond in ways that respect secrecy and silence in the lives of trans forebears.

BW: I think that the dreamlike quality this work has is really effective. It appears as something that is imagined, and I think it appears somewhat hopeful. It’s so fascinating to think about the way that DIY trans media publications like gendertrash and Gender Review and other forms of community-based media from documentary to print really created or began to codify a “trans community” across geography in a communal and political sense, sharing practical advice alongside radical thought about trans life. In a lot of the research I’ve been able to do about local queer history in Halifax, trans people are excluded, as I’m sure is relatable to your own research experience. From institutional archives to personal archives, it is as though there is one transgender folder that has a couple of pieces of paper in it. This is why I think those speculations are so powerful. Have you read “R-Words: Refusing Research?” It’s an academic research method article by Eve Tuck and K.W. Yang.

DJ: Yes! Dr. Sonja Boon was my graduate supervisor and academic mentor, and that article informed a lot of her teaching and writing. The work of scholars and artists like Eve Tuck, Christina Sharpe, Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Viviane Namaste, Mirha-Soleil Ross, Morgan M. Page, and others, influence my practice. What I love about that article is that it sets this clear ethic to say, please rethink your intentions and your place as a marginalized subject within institutions that cannot protect you. In my reading, it communicated: Why offer intimate knowledge to an institution that will neglect you? What does it mean to keep your community safe? Studying that ethic with Sonja has definitely informed this work, and has encouraged me to prioritise an anti-colonial and anti-institutional approach to trans and sex worker histories.

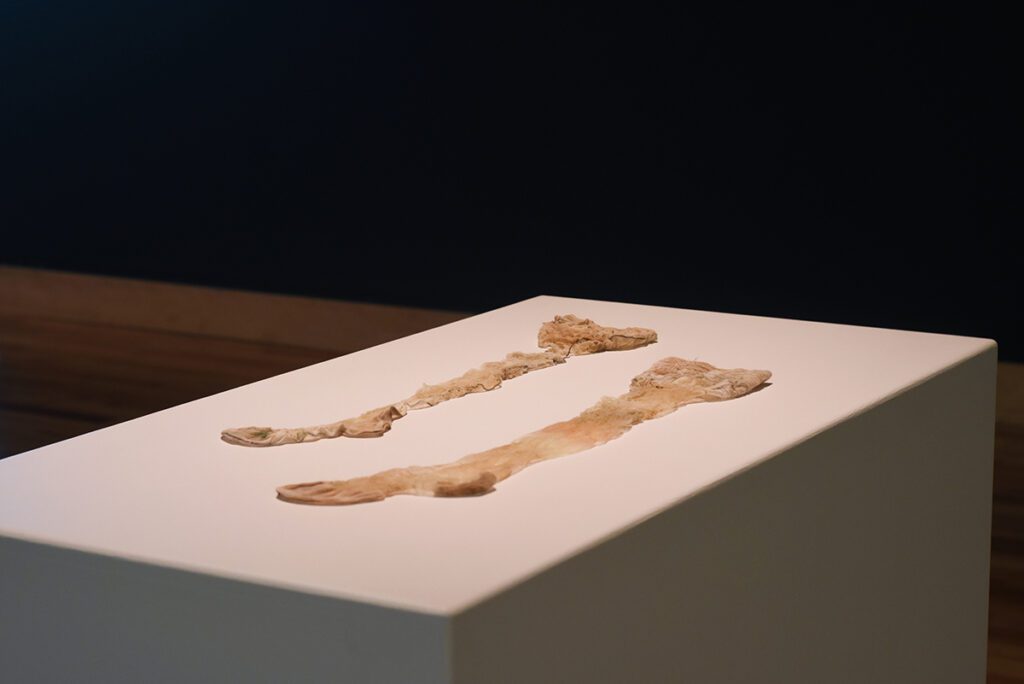

BW: That ethic of, simply put, respect for the dead—that’s huge. Research can really be like digging up someone’s grave. I’m thinking about speculation as an alternative to the colonial archive, in another work of yours, resurfacing you torn-together (2023), which features a pair of pantyhose that I imagine you found on shoreline: it’s this kind of material speculation of what that object could have been, or might have meant. Do you want to talk more about those pantyhose?

DJ: After years of engaging with really troubling archival records of sex workers, I have been asking: When and where does life come through in archives? When and where does embodiment or pleasure come through in archival documents? How can the voices of sex workers be heard? Desire and consent have obviously been absent in criminal-legal records and media reports. I had been looking for a way out of that historical trap. At the point of encounter with those stockings, I had been a full service sex worker for eight and a half years. I think that practices of survival which are so important among sex workers can open up a way of engaging with realities that withstand the violence of dominant cultural histories. The stockings came to me when I needed reassurance. I was at home in the Bay with my partner B.G-Osborne (Oz), and we walked to the beach at the end of the road that my parents’ house is on, which is a magical repository of washed up objects.

The northeast coast of Newfoundland has historically been a major site of resource extraction, and after generations of labour and heedlessness, everything that’s ended up in the water can eventually return. There are so many treasures and strange things that wash up on that beach, including an assemblage of textiles, and every time I’m there I return with new fabrics that inform sculpture and smaller works. On that trip, there was a bundle of dirty fabric and rope and rusted metal, which I brought home and didn’t touch for months. But when I unravelled it, a pair of stockings emerged. Oz and I were both working in our studio, preparing for the exhibition falling through our fingers curated by Emily Critch, and I had been thinking about new work that I wanted to create. Holding the waterworn stockings was an immediate release from years of archival research. I felt a rush of joy holding this soft, delicate, beautiful gift that allowed me to feel closer (albeit through imagination) to sex worker foremothers.

The tenacious reality of nylon stockings surviving the impact of saltwater and the force of the ocean completely filled my heart. It became this formative moment in my practice. I think I’ll always see the stockings as a gift. I wrote poetic fragments to accompany them, which activated intergenerational touches and encounters. It’s also important to acknowledge that throughout late 20th century Newfoundland, several media records included photos of sex workers’ legs with stockings. They made me think deeply about consent and respect because those photos were absolutely taken without the consent of the working girls. For a few years, I wondered how I could respond to that kind of spectacle and erasure, not only as a sex worker, but as an artist. The watery stockings emerged in such a way that could give life and agency back to sex worker bodies; they taught me a method of responding to archival material in refusing institutional records and seeking alternatives.

BW: I think it’s really beautiful that you were able to engage with those topics through a reprieve of childlike whimsy, fantasy, and haptic encounters. I feel like a good way to close up our conversation would be with your recent exhibition, stay here stay how stay, which ran until April 2024 at The Rooms in St. John’s.

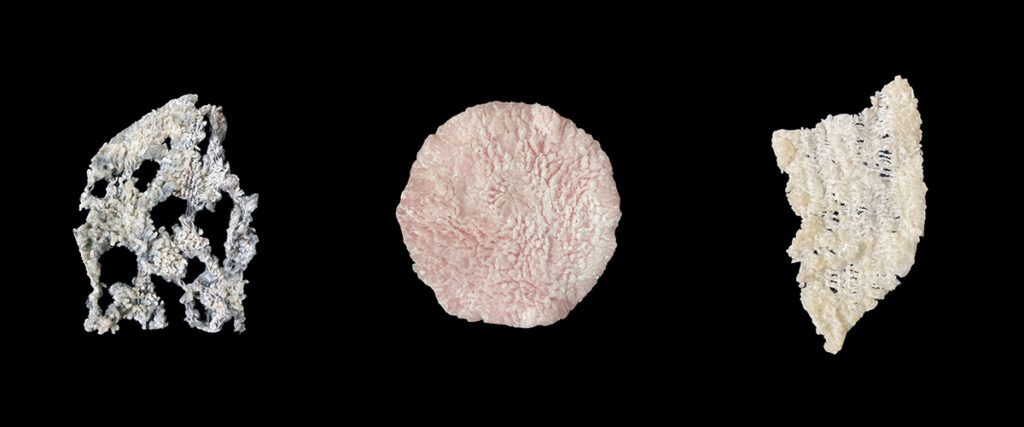

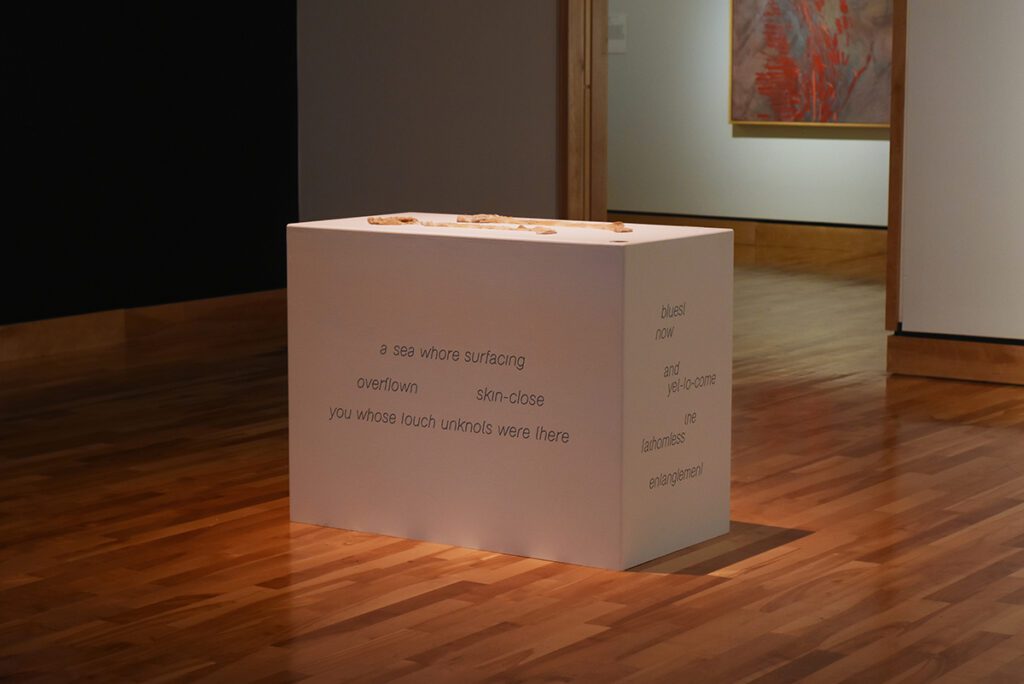

DJ: My show at The Rooms, which was also guest-curated by Emily Critch, explores trans and sex worker embodiments, histories, and intergenerational relationships using textile and wax sculptures, woodcuts, scanner photography, illustrations, sound, and projections. The work is informed by the presence of mermaids and fishy beings as imagined trans and sex worker foremothers. It also responds to the concept of an ocean as a holder of history, which emerges most powerfully within Black Atlantic and Indigenous art and writing, to hold legacies of colonial violence to account. I’ve wanted to follow the work of Bushra Junaid and Camille Turner, among others, to problematize Newfoundland’s position within histories of racial capitalism, and to acknowledge trans and sex worker narratives along the way.

For me, the show embodies a counter-history that is made from interdependent fragments. Emily and I were also imagining the works as islands, and thinking about how they are held together by an archival body, the ocean, or through imagination. They mirror the Bay of Exploits, which is an archipelago. So thinking about rurality, desire, and play has held my inner trans child. The show really opened up a gentle approach for expressing ways that chosen family with trans women and sex workers meets the felt knowledge of my rural settler family. I’ve been calling it an intergenerational labour of love for trans youth, trans women, and sex workers. Play has been really important because I’ve also wanted to release myself from years of difficult archival research. Rethinking the impact of archival research and prioritizing embodied relationships with archival material has signified the importance of thinking counter-historically. It’s an alternative that holds out for the might-have-been and yet-to-come in rural trans and sex worker experiences, which I hope has space for more aliveness.

- The term prostitution is used in reference to the criminalization and surveillance of selling sex in colonial Newfoundland, rather than a term that emerged from sex working women themselves.

- Paul O’Neill, The Oldest City: The Story of St. John’s, Newfoundland (St. Philips: Boulder Publications, 1975/2003).

- Ibid., 173.

- See, for example: Charmaine A. Nelson and Jas Morgan, “Fugitive Portraits,” Canadian Art, July 17, 2017: https://canadianart.ca/interviews/fugitive-portraits/ & Harvey Whitfeild Amani, Biographical Dictionary of Enslaved People in the Maritimes (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2022).

- Tourmaline, “Trans*Revolutions Virtual Symposium,” Barnard Centre for Research on Women, March 27, 2020: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QmDlCaxT8Ok.

- Avery Dame-Griff, The Two Revolutions: History of the Transgender Internet (New York: NYU Press, 2023).

- Rhea Rollmann, “Growing up gay in Don’t-say-gay Newfoundland,” Xtra Magazine, September 6, 2022, https://xtramagazine.com/power/growing-up-trans-newfoundland-235193.

- @sexchange.tbt, https://www.instagram.com/sexchange.tbt/.

- Mirha-Soleil Ross and Xanthra Phillippa MacKay, gendertrash from hell (Toronto: genderpress, 1993-1995).

- Rupert Raj and Nicholas Ghosh, “Gender Dysphoria Clinics in Canada,” Gender Review no. 1 (June 1978): 10.

stay here stay how stay by Daze Jefferies ran from January 20–April 7, 2024 at The Rooms in St. Johns, NL.

falling through your fingers ran from June 3 – September 17, 2023 at Owens Art Gallery in Sackville, NB.

Feature Image: dream zones hormones undertones fish bones, 2022-2023 by Daze Jefferies. Photo courtesy of the artist.